Chimpanzees can change their minds when the facts no longer support their previous beliefs – a rational level of thinking that was once considered uniquely human.

In a series of experiments designed to test the metacognition of these fascinating apes, psychologist Hanna Schleihauf of Utrecht University and her colleagues observed, for the first time, how chimpanzees can weigh different kinds of evidence – and change their beliefs in response to a stronger argument.

"This is really the strongest and hardest test for this understanding of so-called second-order evidence," Schleihauf told ScienceAlert. "I think we have the evidence that we can say, okay, no, rationality in its fundamental form is not uniquely human, but we also share some basic processes of this with chimpanzees."

Related: Cuttlefish Pass Cognitive Test Designed For Human Children

It's the Aristotelian school of philosophy that considers humans the "rational" animal – the one species on Earth with the capacity for reasoned decision-making. In recent years, however, we have started to learn that this assumption may be hubristic, with many animals demonstrating levels of intelligence Aristotle may have thought beyond them.

One putative defining characteristic of human thinking is rationality. This, for the purposes of this research, is defined as the ability to form beliefs about the world based on evidence; but, when new evidence emerges, a rational being can weigh up the two sets of evidence and, crucially, revise their beliefs when the second-order evidence about the evidence is stronger.

As you can probably imagine, this is not an easy thing to test for in non-human animals. Schleihauf and her colleagues designed a series of five experiments to conduct with chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) at the Ngamba Island Chimpanzee Sanctuary in Uganda. Each experiment involved hiding a piece of apple in a box and waiting for the chimpanzee to choose a box based on the evidence presented.

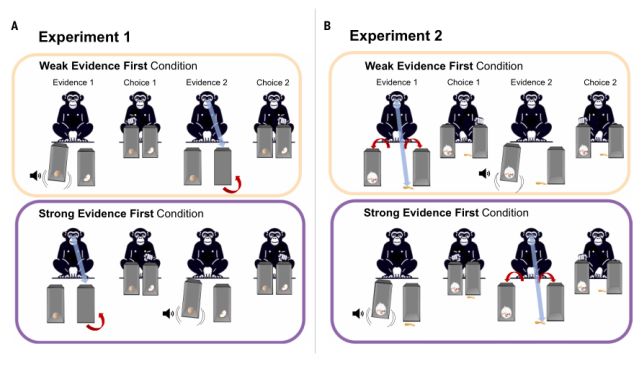

There were several kinds of evidence. Strong evidence was visual: the chimpanzee would see the human physically placing the apple in the box, or see the apple in the box through a clear perspex side. Merely hearing something rattle in the box, or seeing a few crumbs, was classified as weaker evidence.

The first two experiments were the simplest. The chimps were presented with two boxes and then given evidence about each one. When the stronger evidence was presented before the weaker, the chimpanzees tended to stick with their original choice. When the weaker evidence was presented first, they changed their mind. So far, so straightforward.

For the next experiment, the researchers added a third box for which no evidence was provided, then removed the strong-evidence box. Here, the chimpanzees mostly opted for the weak-evidence box over the no-evidence box.

In the fourth experiment, the researchers presented redundant weak evidence or new weak evidence. In the first scenario, the researchers rattled the box twice, so the chimpanzees heard the same piece of food rattling inside the box; but for the second, the chimpanzees were presented with the sound of a second piece of food being dropped in the box.

This is where it gets a bit more interesting. The chimpanzees tended to choose the new, additional evidence over the redundant evidence, suggesting that they can discern between new and old information.

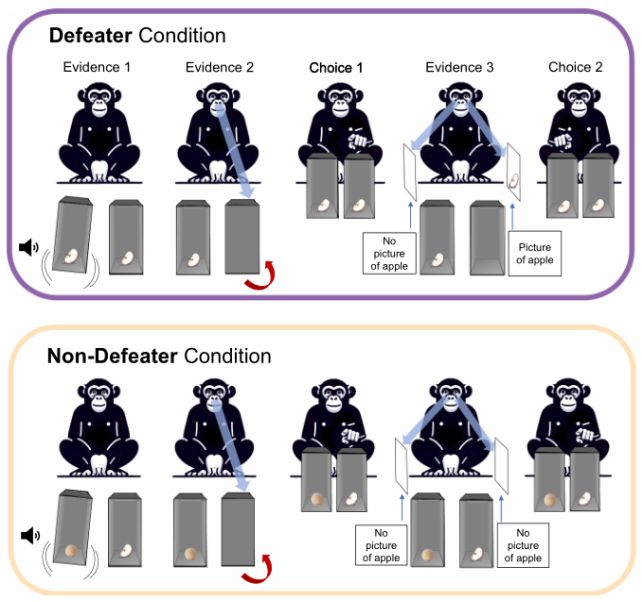

Finally, the fifth experiment was the kicker. The chimpanzees were shown that earlier evidence could be false: the piece of apple turned out to be just a picture on the perspex, or a rock rattling in the box. In this case, the chimpanzees changed their minds more often, rejecting the misleading evidence in favor of more reliable cues.

"I really went in there without the expectation [that it would work], because nobody has done that before," Schleihauf said.

"Animals are not acting purely on instinct, and their behavior has a certain pattern, and they do follow evidence in the world. Reflective responsiveness to reason means you're really aware why you hold certain beliefs. Showing that they changed their mind when the reason was defeated is evidence that they have this capacity."

The results suggest that chimpanzee intelligence might be a little bit closer to how we define human intelligence than we thought. They can weigh and compare evidence, rather than just react to it; track what they know and how they know it; and recognize unreliable evidence and revise their decisions accordingly.

The ability, the researchers believe, could have an origin in the shared ancestor of primates, millions of years ago; if this is the case, it might be testable in other primates, such as capuchins, macaques, and baboons.

In On the Origin of the Species, Charles Darwin wrote, "In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation. Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history."

Perhaps the current psychology of chimpanzees mirrors a similar cognitive stage of development that took place in early humans. There's also a school of thought that proposes that what separates humans from other animals is our ability to cooperate, above and beyond our ability to think rationally.

The new evidence seems to support this idea that intelligence alone is not what makes us human.

"I think there are still vast differences between us, but also more similarities than we assumed there are," Schleihauf said.

The research has been published in Science.