The whole world got excited last month when NASA published the first peer-reviewed paper on the 'impossible' electromagnetic, or EM, Drive, which appears to somehow defy physics by producing thrust without a propellant.

Their verdict was that it seems to work, although a lot of physicists still think the results are flawed. But now researchers in China have announced that they've already been testing the controversial drive in low-Earth orbit, and they're looking into using the EM Drive to power their satellites as soon as possible.

Big disclaimer here - all we have to go on right now is a press conference announcement and an article from a government-sponsored Chinese newspaper (and the country doesn't have the best track record when it comes to trustworthy research).

So until we see a peer-reviewed paper, we really can't say for sure whether the researchers are even testing the drive in space, let alone what their results have shown.

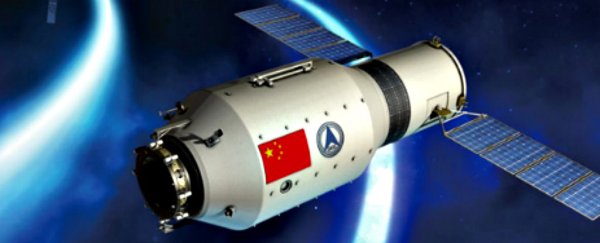

But what the China Academy of Space Technology (CAST) team is saying also corresponds with information provided to IB Times from an anonymous source. According to their informant, China already has an EM Drive on board its version of the International Space Station, the space laboratory Tiangong-2.

We do know from previous papers that Chinese researchers have at least constructed an EM Drive and have been studying it for more than five years now. But there are no published results that we've been able to find that show how positive the results have been.

At the press conference, CAST claim they'd seen the EM Drive producing similar thrust to the NASA team's version.

"National research institutions in recent years have carried out a series of long-term, repeated tests on the EM Drive. NASA's published test results can be said to re-confirm the technology," Chen Yue, head of the communication satellite division at CAST said at this week's press conference, as IB Times reports.

"We have successfully developed several specifications of multiple prototype principles. The establishment of an experimental verification platform to complete the milli-level micro thrust measurement test, as well as several years of repeated experiments and investigations into corresponding interference factors, confirm that in this type of thruster, thrust exists."

Chen also said that CAST had started testing if the EM Drive could actually work in space - something that would be a huge step forward for the controversial propulsion system if it actually works.

In case you've somehow missed it, the EM Drive is a propulsion system that can hypothetically produce thrust just by bouncing microwaves back and forth within its cavity.

That means no heavy propellants (such as rocket fuel) need to be carried on board, and its inventor, Roger Shawyer, predicts that the drive could make it to Mars in just 72 days.

That's all well and good in theory, but the problem is that modern physics can't explain how the EM Drive could work.

According to Newton's third law, everything must have an equal and opposite reaction, so for the EM Drive to produce thrust, it should propel something out the other way. But it doesn't.

Still, several teams around the world have built their own versions of the device and shown that it does seem to produce thrust.

And finally last month NASA published a peer-reviewed paper saying the same thing - after eliminating as many sources of error as they could, they showed the EM Drive still produced small amounts of thrust. They just have no idea how or why.

Needless to say, one paper showing small amounts of thrust produced by a mechanism we don't yet understand isn't enough to say that the EM Drive works - and many notable physicists have vehemently stated that the thrust we're seeing in tests is likely nothing more than an error, or the result of another force we haven't yet accounted for.

So, really, until we test this thing in space, we're not closer to knowing whether or not it works. But the results so far are intriguing enough that physicists are currently planning to do just that.

But if the Chinese team is to be believed - and can produce some solid evidence to back its claims up - they might have already beaten the world to it.

In their press conference, the team also highlighted the many shortcomings of the device and challenges that still need to be overcome.

Chief designer of the CAST communication satellite division, Li Feng, told the media that so far their EM Drive only produces millinewtons of thrust (similar to NASA's version) and to make it functional, they need to get those levels up to between 100 millinewtons and 1 newton.

The team is allegedly now working on the cavity design of the EM Drive and the position of the thruster, before testing their new versions on their satellites in orbit.

If these tests are really happening, it would be great to see some of the results come out in a peer-reviewed paper soon. Until then, we're just going to have to be extra skeptical, and assume nothing until we have some solid evidence.

But it seems that whether we believe them or not, the Chinese team is forging ahead with their EM Drive plans. And we sort of hope they prove us wrong and really do have this thing being tested in space, because it doesn't matter who wins the space race if the result is revolutionising space travel.

"This technology is currently in the latter stages of the proof-of-principle phase, with the goal of making the technology available in satellite engineering as quickly as possible," Li Feng explained at the press conference.

"Although it is difficult to do this, we have the confidence that we will succeed."