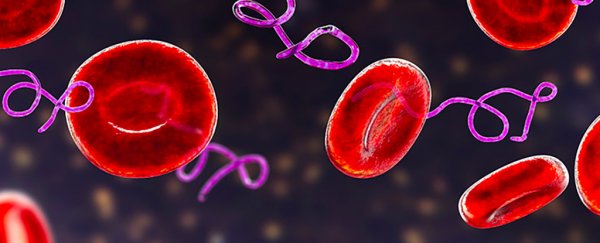

Scientists may have discovered a new way of tackling the lingering, debilitating effects of Lyme disease, the tick-borne illness that can lead to flu-like symptoms and a rash called erythema migrans.

The latest research suggests that dead fragments of Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease, continue to hang around in the body and can cause unhealthy inflammation in the central and peripheral nervous systems even after treatment.

This might explain why some people who get Lyme disease don't make a full recovery after a few weeks of taking antibiotics; instead, they experience ongoing pain, fatigue, and trouble with their cognitive thinking, a condition known as Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS).

"About 10-35 percent of patients treated for erythema migrans or early Lyme disease have persistent or intermittent musculoskeletal, cognitive, or fatigue complaints of mild to moderate intensity at 6 to 12 months of follow up," write the researchers in their published paper.

"Other notable symptoms include joint pain, headache, lower back pain, irritability, paresthesia, sleep issues, and depression."

Patients with PTLDS usually get better eventually, but it can take a long time for people to feel fully well again. There's currently no proven treatment for the condition, as there is for Lyme disease itself.

In this study, the researchers applied remnants of B. burgdorferi on nervous system tissue extracted from euthanized rhesus macaque monkeys, observing the effects on both the frontal cortex in the brain and the dorsal root ganglion in the spinal column.

They found that inflammatory markers were several times higher in samples exposed to B. burgdorferi than in samples exposed to live bacteria. What's more, the dead bacteria also caused cell death in brain neurons.

The effect of B. burgdorferi was particularly evident in the frontal cortex, which helps coordinate movement, organize thoughts, and control working memory. This might be where PTLDS fully or partly originates, the researchers suggest.

"As neuroinflammation is the basis of many neurological disorders, lingering inflammation in the brain due to these unresolved fragments could cause long-term health consequences," says immunologist Geetha Parthasarathy from Tulane University in Louisiana.

Brain scans of patients with PTLDS do indeed show persistent inflammation in the brain, but as yet, the cause of this neuroinflammation hasn't been identified. This latest study looks to be an important step forward in finding that cause.

Another unknown is how B. burgdorferi finds its way into the brain in the first place. It's possible that even after the bacteria is killed, it goes on to cause damage to major organs, such as the brain and the heart.

Further research could look at why the body doesn't clear the bacterial remnants of B. burgdorferi after treatment. This new knowledge might also lead to drugs that can target these remnants and relieve the symptoms of PTLDS.

"Persistence of symptoms in some patients post-treatment indicates that in a subset of these patients, B. burgdorferi fragments in the nervous system could be a cause," write the researchers. "Such antibiotic refractive conditions need novel anti-inflammatory approaches for therapeutics."

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.