Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) doesn't sleep as soundly as we once thought.

Virologists have known for a while now that HIV can hide DNA copies of its own RNA genome within our chromosomes even while the immune system attempts to rid the body of infection.

Two studies have now found tiny fragments of the HIV genome can persist inside immune cells, even when treatment is actively suppressing the virus's ability to replicate.

While these viral RNA splinters are not infectious, researchers believe they could be irritating and exhausting the immune system.

"Most of the virus that remains in the body is defective or junk virus that cannot really multiply, but we found these defective viruses can still produce virus RNA and sometimes proteins," says Daniel Kaufmann, an immunovirologist at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland who co-authored one of the papers.

"It's a deceptively dormant virus," he says. "Even in people who are treated, HIV continues to have some activity, and it continues to interact with the immune system."

Antiretroviral drugs essentially hit a 'snooze button' that stops HIV from replicating inside 'helper T' type immune cells for as long as the person keeps taking the medication. These drugs cause such a large drop in the number of HIV particles that the virus becomes undetectable in the blood. But these drugs don't clear out every shard of viral RNA lodged inside immune cells, the two studies show.

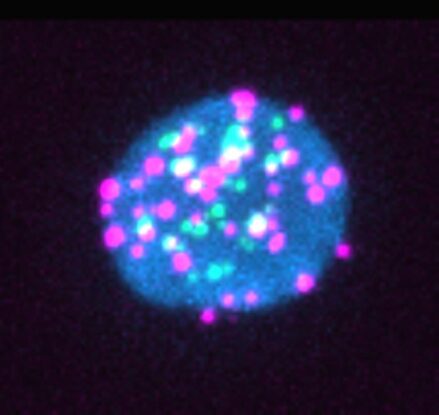

In the first paper, researchers took samples of blood from 18 men being treated for HIV. They searched for HIV gene fragments inside millions of helper T cells using fluorescent RNA probes.

Of 18 people being treated for HIV, 14 had reservoirs of viral RNA, and seven produced viral proteins, including p24; a protein that is a component of HIV's shell and is used in diagnostic tests.

Around 28 in every million immune cells contained 'junk' HIV genetic material, but this was enough to provoke an immune response. The larger the reservoir of HIV gene debris, the more intensely the body responded by mounting an HIV-specific immune response.

We don't know whether such persistent immune activity is helpful or detrimental for the person with HIV. This viral ghost could serve as a welcome reminder for the immune system to stay vigilant, or it could be freaking out and exhausting the army of T cells.

Junk RNA from HIV could cause inflammation, which is known to persist even when people are taking antiretroviral therapy.

"This could be important because a subset of the people who are successfully treated with antiretroviral therapy for HIV still have negative consequences of living with the infection – for example, accelerated cardiac disease, frailty, and premature osteoporosis," says Kaufmann.

The second study confirmed some people being treated for HIV had junk viral RNA inside their helper T cells, which interrupted the development of CD8+ T type immune cells that help fight HIV infection.

"While the replication-competent HIV reservoir is the primary target of HIV cure, our data highlight the pathophysiologic relevance of other fractions of the HIV reservoirs, likely contributing to the deleterious effect of immune activation," the authors of the first paper conclude.

The first and second papers, and the editorial were published in Cell Host & Microbe.