The glorious river of stars, interwoven with dark dust, that makes up the plane of the Milky Way in the night sky may have been hiding in plain sight in art from ancient Egypt.

Some depictions of the goddess of the sky, Nut, that appear on the sides of elaborate coffins actually contain stylized interpretations of the galactic plane. That's according to an analysis of hundreds of coffins, conducted by astrophysicist Or Graur of the University of Portsmouth in the UK.

These depictions, he argues, are so detailed that they include the thick, sinuous rope of dust threaded through the stream of stars that pours across the night sky.

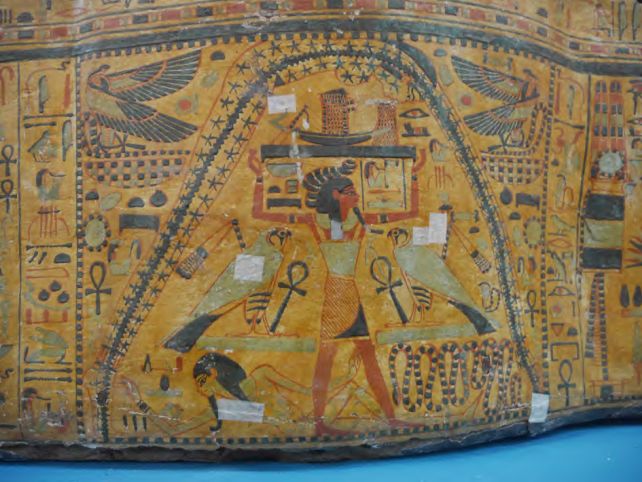

The goddess Nut is one of the oldest in the ancient Egyptian pantheon, ruling over the sky and all things in it. She is often depicted as a naked woman, her body daubed with cosmic objects such as stars and Suns, protectively arched like the sky itself over figures on the ground below.

In a paper published in April 2024, Graur proposed, based on a study of ancient texts, that the ancient Egyptians may have seen the plane of the Milky Way as a manifestation or representation of Nut.

Now, he has followed up his hypothesis by studying the available artwork. The goddess makes frequent appearances in funerary art, since one of her charges was the protection of the dead as they journeyed into the afterlife, so Graur made a study of depictions of Nut as painted on coffin elements up to around 4,600 years ago.

Mostly, the goddess appears either bare or covered with stars. Then, the coffin of a woman who lived during the 21st Dynasty, between 1077 and 943 BCE, yielded a promising feature. Her name was Nesitaudjatakhet, a singer devoted to Mut and Amun-Re, and the painting of Nut on the outside of her coffin included a long, thick, undulating line down the length of the goddess's body, stars painted on either side.

"I think that the undulating curve represents the Milky Way and could be a representation of the Great Rift – the dark band of dust that cuts through the Milky Way's bright band of diffused light. Comparing this depiction with a photograph of the Milky Way shows the stark similarity," Graur says.

It's not the only painting of Nut he found that has this feature, but it does seem to be quite rare. He identified just four other instances where Nut's body was accompanied or marked by a long, wiggly line, and none of those was a coffin.

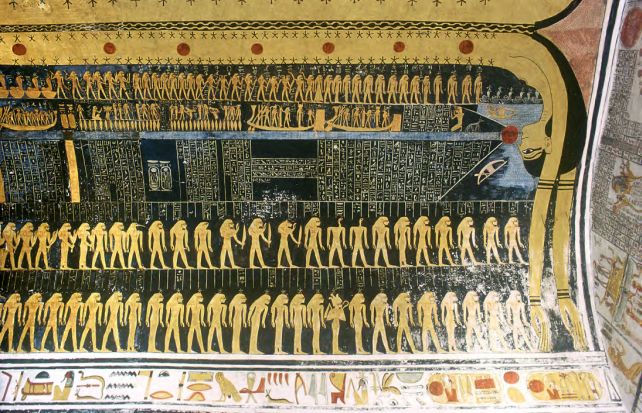

In the tombs of Ramesses IV, VI, and IX, Nut appears twice, representing day and night, with an undulating line separating her two back-to-back depictions.

This rarity, Graur says, suggests that Nut and the Milky Way are not synonymous.

"I did not see a similar undulating curve in any of the other cosmological representations of Nut and it is my view that the rarity of this curve reinforces the conclusion I reached in a study of ancient texts last year, which is that although there is a connection between Nut and the Milky Way, the two are not one and the same," he explains.

"Nut is not a representation of the Milky Way. Instead, the Milky Way, along with the Sun and the stars, is one more celestial phenomenon that can decorate Nut's body in her role as the sky."

The finding highlights how much we don't know about the complex interaction between ancient Egyptian spirituality and science, and how their deities are depicted and why. It also illuminates the value of interdisciplinary research, and the new insights that can be brought with new perspectives.

Finally, Graur urges, it emphasizes the importance of access to resources.

"The catalogs assembled here underline the importance of fully digitizing museum catalogs and providing free access to them through public-facing websites," he writes.

"I am deeply grateful to those museums that have already made their collections accessible in this manner and I urge other museums (and the governments and private foundations that fund them) to create similar digital collections."

His analysis has been published in the Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage.