There are an awful lot of peculiar mysteries in space, made all the more enigmatic because we can't get a close, detailed look at them. One of the most mysterious is a phenomenon called high-velocity clouds - enormous, fast-moving clouds of gas found in the halo of the Milky Way.

But we may soon be able to learn a lot more about them, because scientists have just produced the most detailed map of these clouds to date. Spoiler: they're still pretty odd.

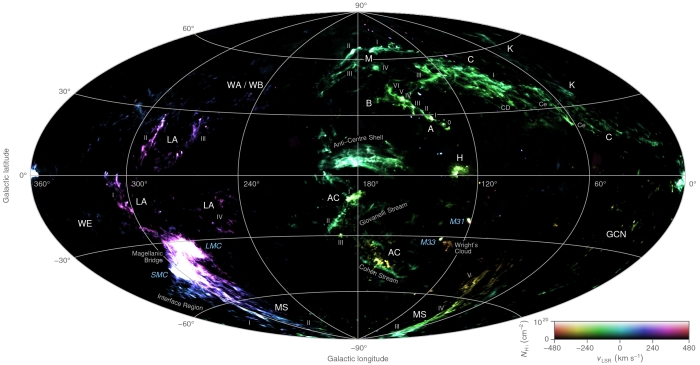

Using radio telescope data, the map shows filaments, clumps and branches within the clouds that have never been seen before.

"It's something that wasn't really visible in the past, and it could provide new clues about the origin of these clouds and the physical conditions within them," said Tobias Westmeier, an astronomer from The University of Western Australia node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research, who created the map.

While we've known about these clouds for some time, they have been an ongoing puzzle for scientists.

They are absolutely huge, some millions of times the mass of the Sun and over 80,000 light-years in diameter.

They drift around in the galactic halo, outside the plane of the Milky Way, although "drift" is relative. They move at incredibly high speeds from 70 to 90 kilometres per second (43.5 to 56 miles per second), independently of and distinguishable from the rotational movement of the galaxy itself.

Map showing column density and radial velocity of the clouds. (ICRAR)

Map showing column density and radial velocity of the clouds. (ICRAR)

They're deeply curious, because no one knows where they came from.

There are hypotheses - they could, for instance, be material falling into our galaxy from outside; or material escaping our galaxy from within; or material that was leftover from the formation of the galaxy that is slowly being incorporated into it.

One high-velocity cloud probably came from an interaction with the nearby Large and Small Magellanic clouds.

But the rest of the clouds are more perplexing, their different compositions pointing to different origins. Some have lower metallicities than what we typically find in the Milky Way, while others are rich in heavy elements.

Westmeier isolated the clouds by masking out gas that was moving at the same speed of the Milky Way, using data from the entire sky HI4PI survey, conducted with the Parkes Observatory in Australia and the Effelsberg 100m Radio Telescope in Germany.

According to his team's calculations, the remaining material - the high-velocity clouds - covers at least 13 percent of the sky.

"These gas clouds are moving towards or away from us at speeds of up to a few hundred kilometres per second," he said.

"They are clearly separate objects."

Westmeier has made his map freely available so that anyone can download and study them, hopefully helping to provide a bit more insight into where these clouds originated - and perhaps into the processes of galactic formation.

The paper has been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, and can be read in full here.