Seven thousand years ago, long before modern industry began to heat the planet, rising seas threatened a community on the coast of Israel. The villagers needed to defend their home, so they built a wall.

It failed. People abandoned the village. The Mediterranean Sea swept inland and drowned the buildings.

But the sea may protect what it ruins. Cool water and a meter-thick layer of sand preserved the paraphernalia of Neolithic life, such as olive pits, bowls, animal bones and graves. The wall stands out: It is a 100-meter row of boulders that runs parallel to the ancient shoreline.

"It's the world's oldest sea wall," said Jonathan Benjamin, a marine archaeologist at Flinders University in Australia. "It's the first evidence of that very real problem that we're dealing with today" - though he was quick to stress the difference between the source of sea-level rise then (the natural aftermath of an ice age) and now (human-made global warming).

Benjamin and his co-authors claim, in a study published in PLOS One on Wednesday, that this is the "oldest known coastal defense worldwide".

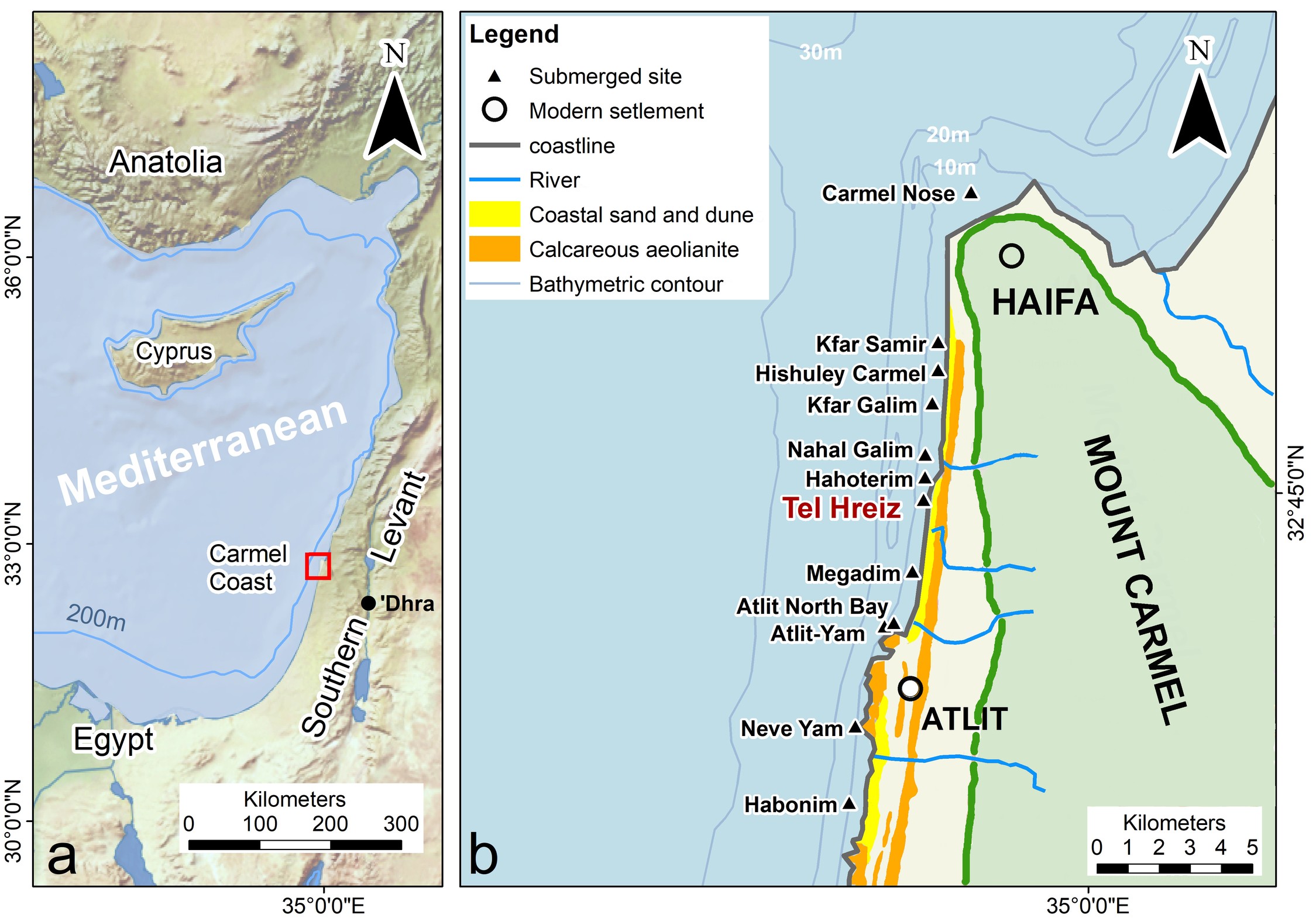

A map of submerged Neolithic settlements off Israel's Carmel coast. (John McCarthy/Galili et al, PLOS One, 2019.)

A map of submerged Neolithic settlements off Israel's Carmel coast. (John McCarthy/Galili et al, PLOS One, 2019.)

The settlement, named Tel Hreiz, was uncovered in 1960 by accident, when divers looking for shipwrecks found flint tools and human bones. Most of the site is submerged three to four meters below sea level.

It drew little attention until 2012, when strong winter storms shifted the sand cover to reveal a line of boulders. Another storm in 2015 exposed additional stones.

Benjamin and marine archaeologist Ehud Galili, of the University of Haifa in Israel, said they debated several alternative possibilities for what the wall could have been — a corral to contain cattle, a dam, a defense against marauders — before dismissing them.

"No enemy was expected from the seaside," Galili said. These people used wooden branches, not stones, to contain their cattle. The sheer size of the wall, its position and the unusual nature of the boulders all pointed toward one purpose: a defense against the sea.

"These people understood that they had to put huge boulders down there, not little stones. They were clearly thinking ahead, that they wanted this wall to last," said Marie Jackson, a research associate professor in geology at the University of Utah, who was not a member of the research team.

"This is a really dynamic sea coast. Without these walls, there would have been little protection."

Tel Hreiz, when it was first established, would have been about 2.5 meters above sea level. The people who lived there belonged to an agricultural society. They raised cattle, hunted deer and cared for dogs and pigs. Hundreds of olive pits scattered at the site suggest these people knew how to extract oil from the fruit.

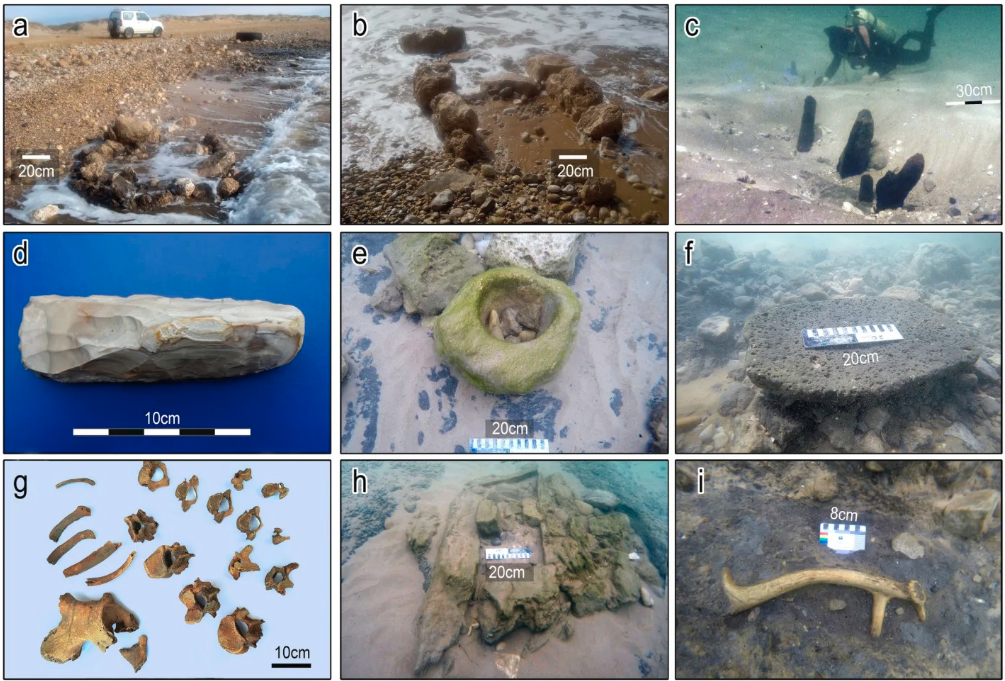

(E. Galili/V. Eshed)

(E. Galili/V. Eshed)

Image: Artifacts from Tel Hreiz include: A and B, stone features in shallow water; C, wood posts dug into the seabed; D, a stone blade; E, a bowl made of sandstone; F, a basalt grounding stone; G, burial remains; H, a stone grave; and I, an antler of Mesopotamian fallow deer.

Radiocarbon dating — from charcoal, wood pieces, animal bones and human remains — indicates the village thrived for several hundred years. Roughly 10 to 20 families lived there, Galili said. It would have been a home for these Neolithic people for at least 10 generations.

"I'm sure that people would have thought that, 'Our family has been here forever, and we need to protect this place,' " Benjamin said.

The settlers of Tel Hreiz could not have known that the sea was rising after what geologists call the "last glacial maximum." At the peak of the most recent ice age, about 20,000 years ago, immense amounts of ice were locked up in the poles. As the ice melted, oceans rose.

Along the coast of Israel, winter storms push waves high up the shore. The rush of water is similar to the storm surges that batter the Atlantic during hurricane season, Benjamin said.

Between 9,000 to 7,000 years ago, the Mediterranean crept up the north coast of Israel at about four millimeters per year, the study authors say. The winter waves were increasingly dangerous.

Hearths and homes at Tel Hreiz, built of simple stone without mortar, would have been vulnerable to the water. "Wave activity can do great damage to such structures," Galili said. "Little by little, the damage became more rapid and more often."

These warning signs may have triggered similar debates to those that coastal communities have now, Benjamin said. "They went to great lengths to protect their home."

Artist's impression of the ancient village and seawall. (John McCarthy & Ehud Galili)

Artist's impression of the ancient village and seawall. (John McCarthy & Ehud Galili)

The boulders that formed the sea wall did not come from nearby. They show no signs of quarrying. Based on the stones' rounded edges, the study authors suspect that rivers weathered the stones. The nearest rivers that contain similar rocks are a few kilometers away.

Jackson, an expert on marine architecture constructed by ancient Romans, has studied harbor structures at Caesarea, a seaside city about 50 kilometers south of Tel Hreiz.

Though Caesarea was built thousands of years later, using different materials, Jackson said these communities shared an "ethos of construction" — a spirit of "building against the sea." The Romans shipped 15,000 to 20,000 kilograms of pumice from Italy to build the Caesarea harbors.

Likewise, it would have taken tremendous effort to construct a wall at Tel Hreiz. "The size and weight of those boulders are stupendous and speaks to the intent of the builders to make something, to build a wall, that had longevity and usefulness," Jackson said.

Building the wall "was a community decision and a communal effort," Galili said. The stones, which weigh as much as 1,000 kilograms, must have been carried by teams of people, or dragged by oxen or, perhaps, rolled.

At the current pace of sea-level rise, in 2100 the ocean will be 65 centimeters higher than it is. In places such as Miami, where the sea has risen about nine millimeters per year since 2006, the rates of rise are possibly double what the people of Tel Hreiz faced.

"They tried to stick it out and eventually they abandoned it," Benjamin said. "And that is a sobering lesson from our human past, isn't it?"

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.