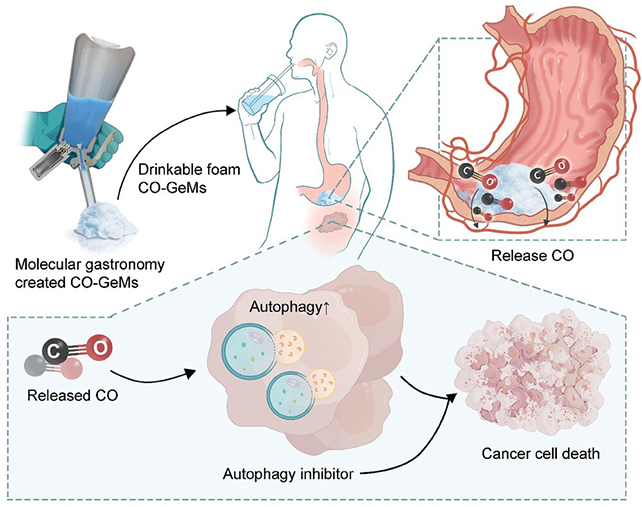

Cancer patients could one day drink foam infused with carbon monoxide to increase the effectiveness of their treatments, after the novel approach was shown to work in tests on mice and human tissue in the lab.

The experiments emerged from unexpected observations in previous studies: cancer patients who smoked ironically had better outcomes for a treatment aimed at restricting a process of cell death called autophagy.

Hijacked by cancers to promote their own growth, putting the brakes on this form of cellular dismantling and recycling ought to impede tumor growth. Yet attempts to stop cancer via autophagy inhibition have had mixed results so far, except in smokers.

"When we looked at how the smokers did in those trials, we saw an increase in overall response in smokers that received the autophagy inhibitors, compared to non-smoker patients, and we also saw a pretty robust decrease in the target lesion size," says oncologist James Byrne, from the Carver College of Medicine at the University of Iowa.

The research team thought carbon monoxide (CO) might be the key. Smokers have more of it in their bodies, and it's also been shown to reduce cell autophagy. Might CO also be helping in killing off cancer cells through autophagy blocking?

Using a technique for creating Gas-Entrapping Materials (or GEMs), a safe-to-drink foam with added carbon monoxide was created. After successful tests in cancerous human and mouse lab cells, the foam was given to mice with pancreatic and prostate cancers, together with autophagy inhibitors.

The dual-action treatment led to significant reductions in tumor growth and progression, promising results that were also repeated to some extent in human cancer cells that the team cultured in petri dishes.

"Smokers have higher carbon monoxide levels and while we definitely don't recommend smoking, this suggested that elevated carbon monoxide might improve the effectiveness of autophagy inhibitors," says Byrne.

"We want to be able to harness that benefit and take it into a therapeutic platform."

It seems that the hypothesized link between carbon monoxide and more effective anti-cancer effects is really there, though further research and clinical trials will be required to see if the same foam could effectively assist cancer patients.

Any treatments that are developed will of course have to be safe to consume – putting CO inside the body isn't generally considered a wise move – but that will be easier once scientists understand exactly how these treatments are boosting the anti-cancer fight.

The team behind the new research thinks it's likely that the approach may well work on other types of cancers than those tested, potentially giving us a new and effective way of reducing tumor spread.

"The results from this study support the idea that safe, therapeutic levels of CO, which we can deliver using GEMs, can increase the anti-cancer activity of autophagy inhibitors, opening a promising new approach that might improve therapies for many different cancers," says Byrne.

The research has been published in Advanced Science.