We could be overlooking an entire population of asteroids that pose a threat to Earth on the very simple basis that they're extremely hard to see.

In the space shared by the orbit of Venus, hundreds of undiscovered asteroids could be orbiting the Sun, hidden from our view simply because of their position.

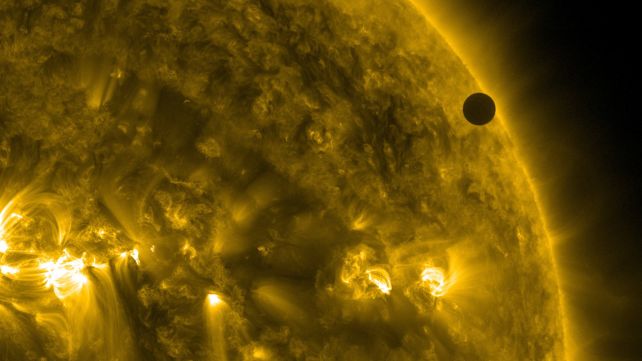

Because they're closer to the center of the Solar System than we are, we have to look in the direction of the Sun to see them – meaning any sunlight they reflect is drowned out by the solar blaze.

Related: New Study Reveals The Potentially Fiery Fate of Inner-Venus Asteroid 'Ayló'chaxnim

"Our study shows that there's a population of potentially dangerous asteroids that we can't detect with current telescopes," explains astronomer Valerio Carruba of São Paulo State University in Brazil.

"These objects orbit the Sun, but aren't part of the asteroid belt, located between Mars and Jupiter. Instead, they're much closer, in resonance with Venus. But they're so difficult to observe that they remain invisible, even though they may pose a real risk of collision with our planet in the distant future."

These objects aren't hypothetical. To date, astronomers have identified 20 asteroids that are co-orbital with Venus. Co-orbitals don't orbit Venus itself, but loop around the Sun in sync with the planet's orbit – sometimes orbiting ahead, sometimes trailing behind, and sometimes crossing to and fro across Venus's path in complex patterns.

What we know about these objects suggests that they are not exactly stable: they're highly chaotic, and the shapes their orbits trace around the Sun change on relatively short timescales, averaging about 12,000 years. Moreover, their paths can only be reliably predicted for around 150 years into the future.

During a random transition in the shape of its orbit, an asteroid can emerge from a relatively stable orbit around Venus and approach Earth, potentially coming close enough to pose a hazard. They can even cross Earth's orbital path.

Scientists believe that these known objects represent just the tip of the iceberg for the population of Venus co-orbitals, with the rest representing a missing majority.

"Asteroids about 300 meters in diameter, which could form craters 3 to 4.5 kilometers wide and release energy equivalent to hundreds of megatons, may be hidden in this population," says Carruba. "An impact in a densely populated area would cause large-scale devastation."

To date, most of the Venus co-orbitals that have been detected have one thing in common: an eccentricity higher than 0.38. Eccentricity is the measure of how round an orbit is; an eccentricity of 0 means a perfectly circular orbit. Earth's orbit around the Sun has an eccentricity of 0.017, so it's very close. The higher the eccentricity, the more elongated the orbit.

Because the known Venus co-orbitals have strong eccentricity, they can move farther away from Venus and closer to Earth, thus becoming easier to see in our sky at twilight, when the Sun is below the horizon but still within range to illuminate a small, nearby object.

Carruba and his colleagues conducted simulations to investigate the population of Venus co-orbitals with lower eccentricity. They focused particularly on the range of possible orbits, whether those orbits pose a hazard to Earth, and whether the Vera Rubin Observatory— which will soon use the largest camera ever built to capture the cosmos in exquisite detail – can help astronomers observe them.

The results revealed a range of orbits with an eccentricity below 0.38 that could pose a threat to Earth in the distant future. Concerningly, the Vera Rubin Observatory would only be able to spot them during limited time windows at certain times of the year.

Meanwhile, this gap in our knowledge about the Solar System poses a particular problem for planetary defense: it's much harder to solve a problem you can't see coming.

There is, however, another solution. An observatory in orbit around Venus, or sharing Venus's orbit, would be much better positioned to see the asteroids that share the planet's corner of the Solar System. It's also worth noting that upcoming missions, such as NASA's NEO Surveyor, are designed to address this inner Solar System blind spot.

"While surveys such as those from the Rubin Observatory might be able to detect some of these asteroids in the near future," the researchers write in their paper, "we believe that only a dedicated observational campaign from a space-based mission near Venus could potentially map and discover all the remaining 'invisible potentially hazardous asteroids among Venus' co-orbital asteroids."

The research has been published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.