One of the first major findings from the Rosetta mission has shed light on the origin of Earth's water - and revealed that it most likely didn't come from comets, as had previously been suggested.

The Rosetta spacecraft has been analysing the water frozen on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (or Comet 67P for short) since it first started orbiting it, and has now discovered that its isotope ratio is significantly different to the water found on Earth.

In fact, the Rosetta scientists argue that it's more likely that rocky asteroids, rather than comets, brought water to our planet.

Their findings are published today in Science, and contradict data collected from a comet three years ago, which showed that comets may have deposited water on Earth.

"We knew that Rosetta's in situ analysis of this comet was always going to throw up surprises for the bigger picture of Solar System science, and this outstanding observation certainly adds fuel to the debate about the origin of Earth's water," said Matt Taylor, the European Space Agency (ESA)'s Rosetta project scientist, in a press release.

At the moment, one of the leading theories on where Earth's oceans came from is that, around 4 billion years ago, during the Late Heavy Bombardment period, comets and asteroids slammed into our cooling planet and delivered water. It's also believed that they may have brought the organic molecules that served as the building blocks for life.

This is one of the main reasons scientists are so keen to study ancient comets such as comet 67P, in order to find out more about the organic molecules and the "flavour" of the water they carry, and work out whether these have any similarities to what we have here on Earth.

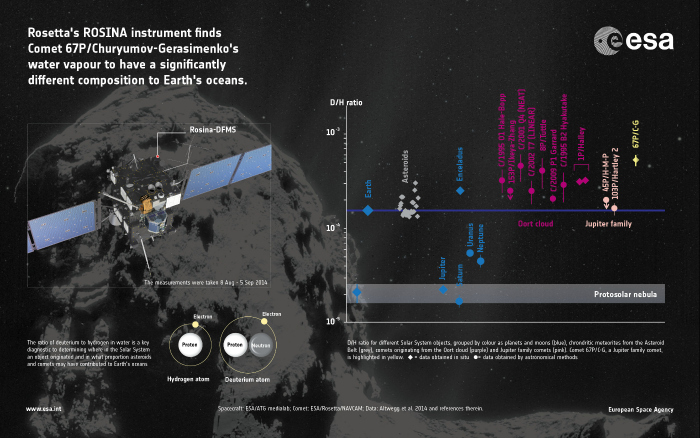

Scientists have now collected data from 11 comets, the ESA reports, and it's becoming clear that the story is more complicated than we'd previously imagined.

In order to work out whether water from a comet is similar to water on Earth, scientists examine the ratio of deuterium - a heavy hydrogen isotope - to regular hydrogen. On Earth, this ratio is pretty small, around three deuterium molecules to 10,000 hydrogen molecules.

Using a technique called mass spectrometry, Rosetta was able to analyse the ratio of the water on Comet 67P, and discovered that its ratio of deuterium to hydrogen is around three times higher than the water on Earth.

Around 10 years ago, this wouldn't have come as much of a surprise, as several of the comets previously analysed had around double the deuterium-hydrogen ratios than Earth. But then back in 2011, a comet called Hartley-2 was studied, and it had the same ratio as Earth.

Hartley-2 is what's known as a Jupiter-family comet, just like Comet 67P. Because both originate from the same region of the Solar System, some scientists had thought that Comet 67P may also contain similar ratios of deuterium-to-hydrogen.

Instead, they found the biggest chemical difference between comet water and Earth's water detected so far.

ESA

ESA

Previous research on rocky asteroids, however, has shown that overall the deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio of their small amounts of water matches that on Earth.

"Our finding…rules out the idea that Jupiter-family comets contain solely Earth ocean-like water, and adds weight to models that place more emphasis on asteroids as the main delivery mechanism for Earth's oceans," said the ESA's Kathrin Altwegg, the principal investigator on the project and lead author of the paper, in the release.

However, not everyone is convinced. Physics and astronomy professor Humberto Campins from the University of Central Florida in Orlando told Alexandra Ossola from The Verge:

"Rosetta's findings are interesting and important, but I wouldn't necessarily say that this information makes asteroids a more likely source."

As Ossola writes for The Verge, the small amount of data we have access to isn't enough to draw definite conclusions, and we still don't know what forces affect the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen out in the Solar System.

"When you look at this data carefully, the conclusion isn't so black and white, but it's still an interesting result," Campins told The Verge.

The next important step will be for Rosetta to continue monitoring the composition of the water on Comet 67P as it approaches the Sun, and notice any changes in its behaviour.

Scientists will also be following the results of Japan's Hayabusa-2 mission closely, which is set to bring an asteroid sample back to Earth for analysis by 2020. NASA will also be launching a mission called OSIRIS-REx in 2016 with a similar goal. The data we collect about the water on these asteroids will take us a big step closer to understanding exactly how our planet got its water - and potentially also the building blocks of life.

It's pretty exciting research, because if we can find out how water and organic molecules were delivered to Earth, then it will shed some light on whether life could have been delivered around the rest of the Solar System. And that would be huge.