To any potential ETs searching for their own alien life forms, Earth would have attracted attention more easily during the time of the dinosaurs than it would today.

Astrobiologist Rebecca Payne and astronomer Lisa Kaltenegger from Cornell University modeled the last 540 million years of Earth's history – the Phanerozoic Eon – to see how different biomarkers used to detect signs of life over vast distances may have changed.

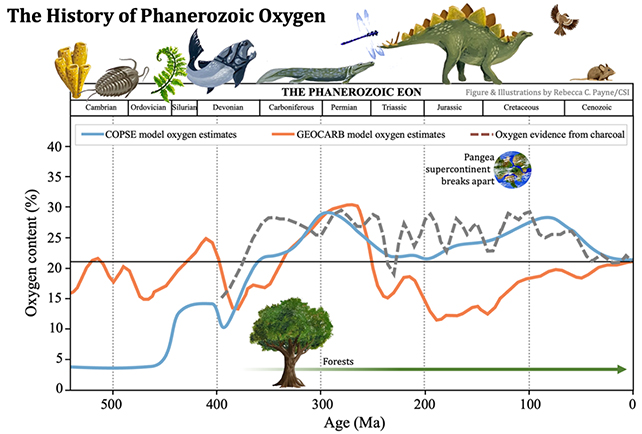

They found that two key biomarker pairs would have been stronger some 100 to 300 million years ago: oxygen and methane, and ozone and methane. That's primarily down to a proliferation of greenery delivering significantly higher levels of oxygen into the atmosphere back then.

That means any hypothetical alien telescopes looking for light fingerprints (or transmission spectra) could have spotted our planet far more easily during the Jurassic era than they might do today.

"Modern Earth's light fingerprint has been our template for identifying potentially habitable planets, but there was a time when this fingerprint was even more pronounced – better at showing signs of life," says Kaltenegger.

"This gives us hope that it might be just a little bit easier to find signs of life – even large, complex life – elsewhere in the cosmos."

All sorts of factors influence the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere, from the level of forest cover on land to the different types of marine species in the ocean, and the dominating patterns of weather.

For much of the last 400 million years or so, atmospheric oxygen levels are thought to have been within the 16-35 percent range. This is known as the 'fire window': any less and fires wouldn't light, any more and it would be very hard to extinguish them.

"The Phanerozoic is just the most recent 12 percent or so of Earth's history, but it encompasses nearly all of the time in which life was more complex than microbes and sponges," says Payne.

Astronomers are scouring the rest of the Universe for the same light fingerprints as well, looking for signs of an atmosphere that can support a form of life we might be familiar with. Now we know what a Phanerozoic planet should look like, that search can be more precise.

With the advanced tech on board the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scientists now have the ability to analyze exoplanet atmospheres, although we still can't be sure that life would evolve in the same way as it has on Earth.

"Hopefully we'll find some planets that happen to have more oxygen than Earth right now, because that will make the search for life just a little bit easier," says Kaltenegger.

"And who knows, maybe there are other dinosaurs waiting to be found."

The research has been published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters.