The highest sea cliffs in England have been hiding the oldest fossilized forest yet found on planet Earth. The long-lost ecosystem's palm-like trees, called Calamophytons, are 390 million years old.

That's roughly three or four million years older than the previous record holder, found across the Atlantic in New York State.

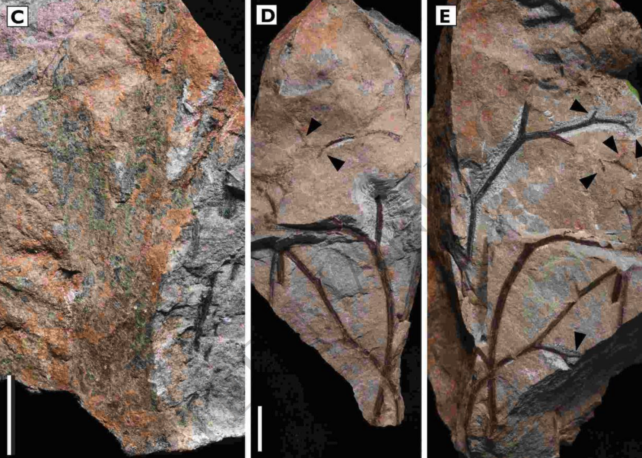

In southwest England, the red sandstone rock face where scientists found the imprints of logs, roots, and twigs was once considered "barren of trace fossils".

Recent investigations, however, have found the site actually provides a wonderful cross-section of life in the Devonian Period – a time when plummeting sea levels pulled back the ocean to create two massive continents known as Gondwana and Euramerica.

Animals and primitive plants alike were quick to make use of the new environment. The first trees to colonize the supercontinents were unlike anything you'd see today. Initially, they didn't have roots, leaves, spores, seeds, or any vascular system to transport water and nutrients, forcing them to stick close to coastlines and rivers.

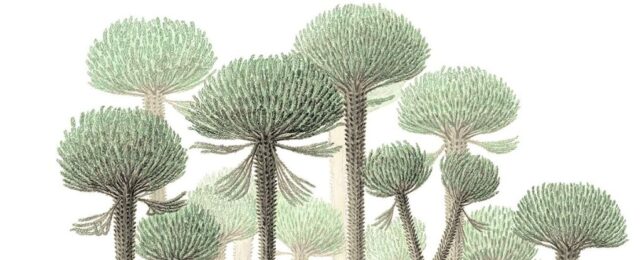

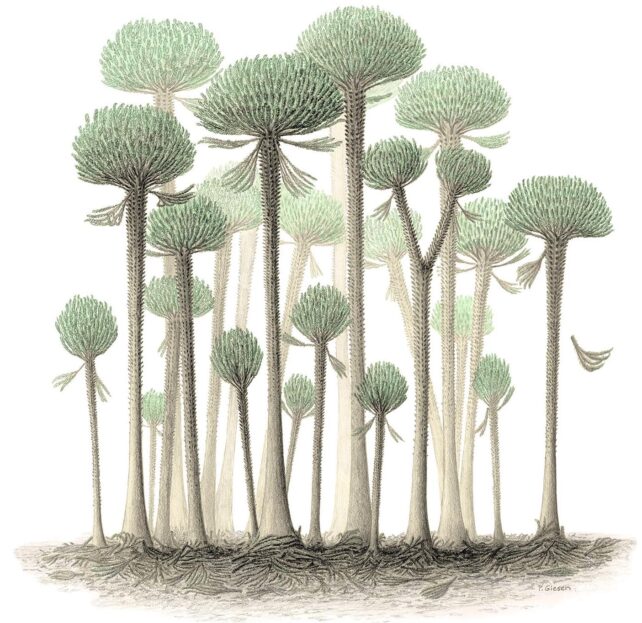

The Calamophyton trees discovered on the Somerset coastline near Minehead had evolved roots and strands of vascular tissue in their stems, but they were only two to four meters high, and their trunks were thin and hollow.

Others of their kind have previously been discovered in fossil form in Germany, New York, and China. When the Gondwana supercontinent existed, Germany used to be connected to this very part of England, so it makes sense that they'd share vegetation.

"When I first saw pictures of the tree trunks I immediately knew what they were, based on 30 years of studying this type of tree worldwide," explains Christopher Berry from the University of Cardiff.

"It was amazing to see them so near to home."

Even better, some of the fossilized trees are preserved exactly where they grew or fell, giving scientists a first glimpse into the layout of the forest ecosystem. Unlike the fossil forest found in upstate New York, the trees in this ancient floodplain are shorter and appear to have grown close together, tightly packed in.

"This was a pretty weird forest," says geologist Neil Davies from the University of Cambridge.

"There wasn't any undergrowth to speak of and grass hadn't yet appeared, but there were lots of twigs dropped by these densely-packed trees, which had a big effect on the landscape."

Calamophyton trees had no leaves, but they were covered in hundreds of little twigs that were regularly shed. In fact, in one lifetime, Calamophyton trees may have shed as many as 800 branches.

That one tree's trash was likely another plant's treasure. As the woody debris accumulated on the forest floor, Earth's soil was infused with its first reserves of organic matter.

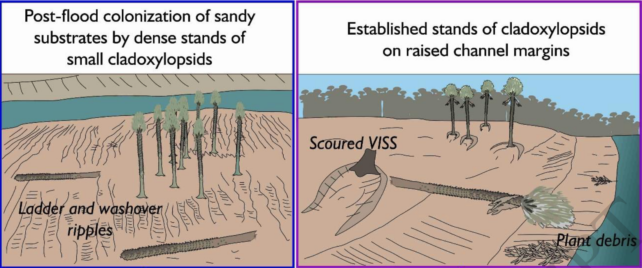

All those tens of millions of years ago, the forest ground would have been covered in "exceptionally abundant plant debris", write geologists from Cambridge and Cardiff.

Surrounded by a network of rivers and channels, seasonal floods would have been common. The trees probably evolved deeper roots to survive bouts of water scarcity.

These roots, in turn, would have stabilized and sculpted the land to form the slopes of hills, river bars, and channels for other plants to then colonize.

As water washed through the floodplain, it deposited mud in ripples around the vegetation in ways that were later fossilized, preserving the plants and their position for millions of years.

"The Devonian period fundamentally changed life on Earth," says Davies.

"It also changed how water and land interacted with each other, since trees and other plants helped stabilize sediment through their root systems, but little is known about the very earliest forests."

The Devonian is sometimes called the 'age of fishes', but given how much plants like Calamophyton appear to have altered Earth's landscape, the time could just as well be known as the age of trees.

The study was published in the Journal of the Geological Society.