You can impress family members and friends with magic tricks, but you can also use them to study the differences in perception between animals and humans – and a new study highlights how Eurasian jays aren't quite as susceptible to sleight of hand as we are.

Jays and other large-brained birds often use techniques similar to sleight of hand to keep food concealed in their beaks and away from potential scavengers, which adds another level of intrigue when it comes to how they react to magic performed by a person.

"A magic trick works because it violates your expectations," psychologist Elias Garcia-Pelegrin, from the University of Cambridge in the UK, told The Academic Times.

"As such, it is quite interesting to use these magic effects to check if the expectations of other minds are like ours."

A series of tests involving both birds and people showed that the jays were less easily fooled than people by sleight of hand techniques that involved expected motion rather than actual motion – a sign that they don't anticipate actions such as grabbing in the same way that we do.

A Eurasian jay makes a choice after an illusion. (Elias Garcia-Pelegrin)

A Eurasian jay makes a choice after an illusion. (Elias Garcia-Pelegrin)

Six Eurasian jays (Garrulus glandarius) and 80 people were shown tricks where a worm - a lovely bit of food for a jay - was or wasn't passed between two hands.

The birds and human participants were then prompted to indicate where they thought the worm had ended up, with the jays having been trained to peck at the fist holding the food.

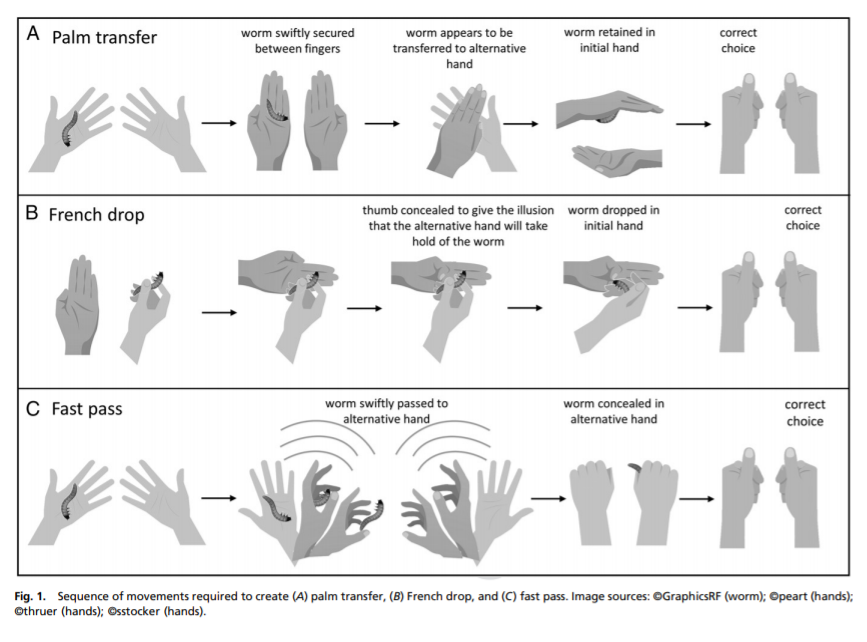

Three techniques were demonstrated: the palm transfer and the French drop, which use dummy gestures and movement to make you think something has moved when it hasn't, and the fast pass, which uses really quick movements as its key deception.

(Garcia-Pelegrin et al., PNAS, 2021)

(Garcia-Pelegrin et al., PNAS, 2021)

The people involved in the study were largely taken in by all three sleight of hand methods, but the birds were only tricked by the fast pass.

A series of test conditions where the passing movement was made slowly suggested that unless the birds actually saw the worm move physically from one hand to another, they assumed it hadn't been transferred over.

"Our results suggest that jays might have different expectations from humans when observing these transfer techniques," write the researchers in their paper.

While the findings are useful for any magicians with a booking at an aviary, they also show how blind spots in perception can vary between species, as well as offering more insight into how these sorts of cognitive processes might have evolved in different animals.

The next step in the research is to work out exactly what's going on – are the differences down to the actual way the birds perceive what is happening, or is it that they're just not paying attention quite as closely? A wider selection of birds would be helpful next time too, to back up what's been observed here.

"Our results showing that Eurasian jays fail to perceive fast-paced movements raise the intriguing question as to whether the jays themselves take advantage of such constraints when pilfering or protecting caches from thieving conspecifics [members of same species]," the team writes.

Ultimately the researchers are looking to develop magic tricks that are tailor-made for birds and the way that they see the world – tricks that would be able to reveal more about how these creatures see and interpret the world around them.

"Magic effects can provide an insightful methodology to investigate perception and attentional shortcomings in human and non-human animals and offer unique opportunities to highlight cognitive constraints in diverse animal minds," conclude the researchers.

The research has been published in PNAS.