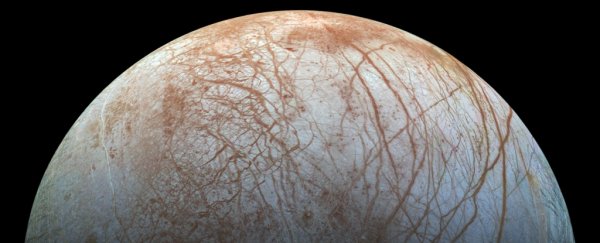

Jupiter's ice-encrusted moon Europa is increasingly looking like the best place in the Solar System to search for extraterrestrial life.

New modeling suggests that the rocky mantle, deep below the thick ice and salty ocean, could actually be hot enough for volcanic activity. Moreover, it could have been this hot over most of its 4.5-billion year lifespan.

The finding has direct implications for the possibility of life lurking on Europa's seafloor.

"Our findings provide additional evidence that Europa's subsurface ocean may be an environment suitable for the emergence of life," said geophysicist Marie Běhounková of Charles University in Czechia.

"Europa is one of the rare planetary bodies that might have maintained volcanic activity over billions of years, and possibly the only one beyond Earth that has large water reservoirs and a long-lived source of energy."

You might think an icy world far from the life-sustaining warmth of the Sun – where surface temperatures tend to peak at around -140 degrees Celsius (-225 degrees Fahrenheit) – would be an unlikely place to find living organisms, but there's actually precedent right here on Earth.

True, most life here does rely on a food web based on photosynthesis… but in some extreme environments, where the Sun never shines, life has found another way.

In the dark depths of the ocean, too deep for sunlight to penetrate, volcanic vents seep heat into the waters around them. There, life is built on chemosynthesis, bacteria that harness the energy within geochemistry rather than solar energy to produce food.

With the bacteria come other organisms that can eat them, thus creating an entire ecosystem down there in the dark.

We know that Europa, beneath its thick shell of ice, harbors a global ocean – we've seen liquid water shooting out of cracks in the ice in the form of geysers. We've also detected what is very probably salt. This answers some of the conditions for chemosynthetic hydrothermal life as we know it.

What we don't know is whether Europa has volcanic activity below its seafloor, opening into vents like they do here on Earth.

It's possible; Jupiter's moon Io is the most volcanic world in the Solar System, due to the constant stresses placed by Jupiter's gravitational tugging (and possibly the gravitational tugging of the other Jovian moons) that heat the interior.

Given that Europa is farther from Jupiter than Io, though, doubt remains - so Běhounková and her colleagues decided to try and figure it out.

They used detailed modeling to simulate the evolution and heating of Europa's interior from the time of its formation. They found several mechanisms at play that could be working to keep the planet from freezing completely.

Firstly, heat released by radioactive decay of elements in the mantle likely contributed a significant fraction of the moon's internal heat, especially early in Europa's history.

Over time, though, the changing stresses generated by tidal forces exerted by the moon's elliptical orbit around Jupiter should have produced ongoing flexing in Europa's interior.

This flexing, in turn, produces heat - and it should be sufficient heat to melt rock into magma, resulting in volcanic activity that could be ongoing today, especially in the higher latitudes close to the polar regions.

These simulations have given scientists signs of this activity to look for when probes such as NASA's Europa Clipper and the European Space Agency's JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) mission (due to launch in 2024 and next year respectively) get up close and personal with Europa.

Gravitational anomalies could suggest the presence of deep magmatic activity, and the anomalous presence of hydrogen and methane in Europa's thin atmosphere could be the result of chemical reactions occurring at hydrothermal vents. Deposits of fresh oceanic materials on Europa's surface could indicate subsurface activity too.

"The prospect for a hot, rocky interior and volcanoes on Europa's seafloor increases the chance that Europa's ocean could be a habitable environment," said Europa Clipper Project Scientist Robert Pappalardo of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who wasn't involved in the research.

"We may be able to test this with Europa Clipper's planned gravity and compositional measurements, which is an exciting prospect."

First, however, we'll have to wait a few more years for the spacecraft to get there. Curse the tyranny of distance!

The team's research has been published in Geophysical Research Letters.