The Solar System may be an even soggier place than we suspected.

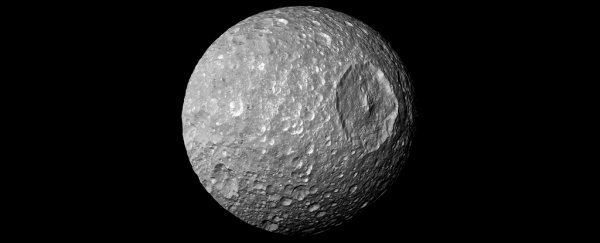

New analysis of one of Saturn's moons suggests that it may harbor a liquid ocean. No, not the usual suspects – the new culprit is Mimas, the little moon with a big crater, which gives it more than a passing resemblance to the 'Death Star' from Star Wars.

A slight, peculiar wobble exhibited by the moon and detected by astronomers could be the result of a liquid internal ocean, according to new research.

If this is the case, Mimas will join other Solar System moons such as Europa and Enceladus in the category of 'IWOWs' (interior water ocean worlds). But if so, it's an IWOW of a kind we've never seen before, expanding our understanding of what's possible.

"Because the surface of Mimas is heavily cratered, we thought it was just a frozen block of ice," says geophysicist Alyssa Rhoden of the Southwest Research Institute.

"IWOWs, such as Enceladus and Europa, tend to be fractured and show other signs of geologic activity. Turns out, Mimas' surface was tricking us, and our new understanding has greatly expanded the definition of a potentially habitable world in our Solar System and beyond."

Here on Earth, life mostly relies on sunlight to survive, but there are a few places where organisms can thrive in complete darkness.

At the bottom of the ocean is one of them, clustered around hydrothermal vents that release heat and nutrients from Earth's interior. Here, life relies not on photosynthesis, but on chemosynthesis, harnessing chemical reactions to synthesize food.

This became relevant to our search for extraterrestrial life when Jupiter's moon Europa and Saturn's moon Enceladus were found to harbor liquid oceans beneath their icy crusts.

Geological activity deep within the moons, driven by the tidal stretching and pulling caused by gravitational interactions with their respective planets, generates sufficient heat to keep water below the surface from freezing.

Mimas, however, did not appear to belong to this group of moons. It's closer to Saturn and has a more eccentric (elliptical) orbit than Enceladus, which means it ought to experience stronger tides; yet its activity is much lower than that of Enceladus.

This led scientists to the conclusion that Mimas was probably frozen solid, and thus less prone to deformation.

But the vexing problem of its libration, or physical 'wobble', as detected by Saturn probe Cassini, remained. If Mimas was solid, it shouldn't wobble in the same way.

The moon's libration suggested that either it had a differentiated core or a liquid ocean – something preventing the core from being rigidly connected to the surface, allowing the latter to shift around.

Rhoden and her team wanted to investigate the possibility of a liquid ocean. They needed to resolve the generation and dissipation of sufficient heat from the moon's interior to keep water inside the moon liquid, while still maintaining a very thick frozen outer shell.

"Most of the time when we create these models, we have to fine-tune them to produce what we observe," Rhoden explains. "This time evidence for an internal ocean just popped out of the most realistic ice shell stability scenarios and observed librations."

According to their models, the ice shell of Mimas is between 24 and 31 kilometers (15 to 20 miles) thick, under which a global ocean swirls. Since Mimas is just 396 kilometers (246 miles) in diameter, this is comparatively very thick; Enceladus' icy shell ranges between 5 and 35 kilometers, for a diameter of 513 kilometers.

The team also found that heat flow from Mimas' surface is likely very sensitive to the thickness of the ice in any given region. Future probes ought to be able to measure this directly, both on Mimas and other IWOWs.

Finally, the models suggest that, in addition to a liquid ocean, Mimas also has a differentiated core. This contradicts our previous models of Mimas' evolution, since early differentiation of the moon should have produced a very different orbit to the one it has today. This makes Mimas potentially very interesting for further study and exploration.

"Although our results support a present-day ocean within Mimas, it is challenging to reconcile the moon's orbital and geologic characteristics with our current understanding of its thermal-orbital evolution," Rhoden says.

"Evaluating Mimas' status as an ocean moon would benchmark models of its formation and evolution. This would help us better understand Saturn's rings and mid-sized moons as well as the prevalence of potentially habitable ocean moons, particularly at Uranus. Mimas is a compelling target for continued investigation."

The research has been published in Icarus.