About 66 million years ago, a herd of herbivorous dinosaurs succumbed to drought – tragically, just hours or days before heavy rains fell.

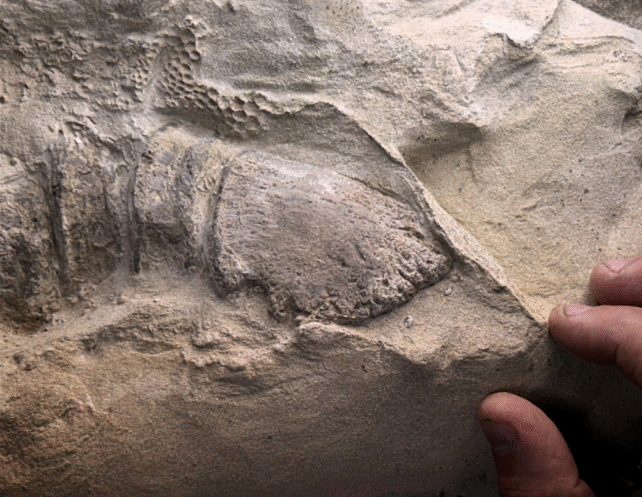

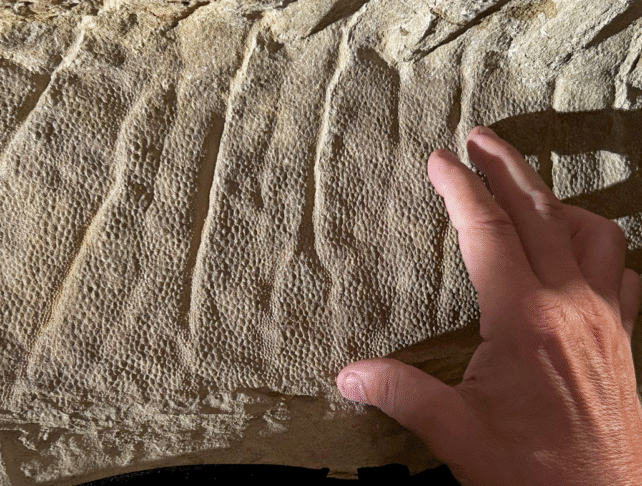

We know this because they left some of the most incredibly well-preserved dinosaur 'mummies' ever found, consisting of clay molds of features such as skin, spikes, and the first known examples of hooves in a reptile.

These mummies belonged to a species called Edmontosaurus annectens, duck-billed herbivores that roamed what's now North America like ancient buffalo. They're among the dinosaurs we know the most about, because they're quite common and often preserve well.

Related: 'Beyond Doubt': Proteins in Fossil From Actual Dinosaur, Claim Scientists

Paleontologists at the University of Chicago have now led a study closely examining several dinosaur mummies from the 'mummy zone', a 10-kilometer-wide region in the US state of Wyoming with apparently exceptional preservation conditions.

Two recently discovered specimens reveal some never-before-seen features. The first is a juvenile, estimated to be about two years old when it died. This is the first large-bodied dinosaur to keep its full fleshy profile, which includes a crest that runs down its neck and spine.

The second specimen – an early adult, thought to be between five and eight years old – still bears a whole row of small spikes running down its back, from its hips to the tip of its tail. Some of these have been found before, but never in their entirety.

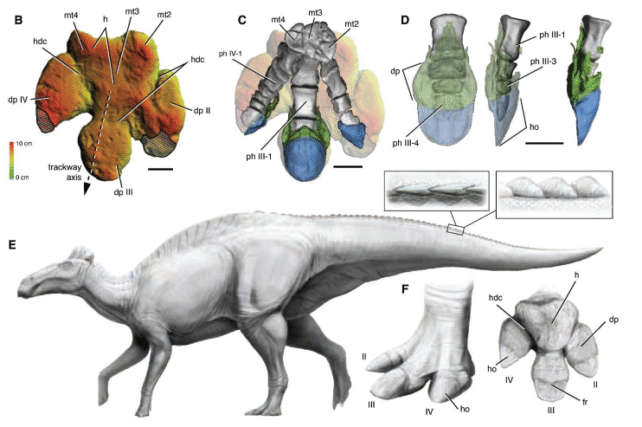

But the most intriguing find is that the toes of Edmontosaurus' hind feet are capped in hooves. This marks not only the first find of hooves on a dinosaur, but on any kind of reptile. On top of that, with an age of 66 to 69 million years, it's the oldest known example of a hoof on any animal.

"Hooves likely evolved even earlier in the Jurassic among armored ornithischians (stegosaurs, ankylosaurs), the manus and pes of which are stoutly proportioned and… are linked to footprints with rounded toe imprints," the researchers write in their paper.

But how were these mummies made? To investigate, the team analyzed the samples with optical scans, X-rays, CT scans, and electron microscopes and found that, sadly, there's no sign of any organic material left, nor any impressions of internal structure.

Instead, it looks like all of the external structures are preserved as a thin layer of clay, less than 1 millimeter thick, which was formed by the material congealing onto a microbial biofilm that covered the surface of the carcasses as they decayed.

These finds reveal the story of the animals' deaths in startling detail. Their wrinkly skin, which was closely draped over the bones, indicates the bodies sat out in the hot Sun for a few hours or days after death. A drought has been directly identified as the cause of death for at least some of the mummies.

That makes what happened next tragically ironic. Each mummy seems to have been quickly encased in a big body of sediment, with mixed mud and broken tree trunks in the same layers.

"These details support carcass burial by floodwaters at or near the site of death over a matter of hours or, at most, days," the researchers write. "We conclude that the span of time between death and sudden burial of the four E. annectens mummies in the 'mummy zone' was on the order of a week or weeks within a single season."

The majority of what we know about dinosaurs comes from fossilized bones, but occasionally, signs of softer tissues survive. Skin, feathers, scales, and even organs have been found, filling in some of the blanks that bones alone can't fill.

These mummified dinosaurs provide some of the clearest glimpses of ancient animals short of traveling back in time.

The research was published in the journal Science.