The first American settlers may have arrived across a coastal "kelp highway" from northeast Asia, and arrived well before another culture that was previously thought to be first.

The Clovis culture that appeared in the Americas some 13,500 years ago is widely accepted to be the ancestor of most of the continents' indigenous cultures. However, with a growing body of evidence to back them up, anthropologists have declared the idea that the Clovis people were here first is now… dead.

The Clovis people were so-named because artefacts of their culture were first found in Clovis, New Mexico in 1932. There are very few skeletal remains, but those of an infant boy named Anzick-1 from a Clovis burial site in Montana showed a genetic connection to modern Native American populations - and Siberia.

It's thought that the Clovis people made their way to the Americas over land that used to span the Bering Sea during the last Ice Age, called the Bering Land Bridge, from Siberia.

Not everyone agrees with the Siberian origin, since Anzick-1's genome showed genetic divergence from Siberian populations, but that the Clovis people existed is not under dispute.

Now, according to a team of anthropologists from the US, more and more evidence points to earlier settlement - at a time when passage through the Bering Land Bridge would have been blocked by glaciers. Such arrivals would have had to travel a different route.

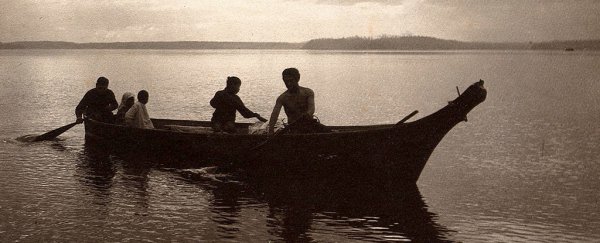

"In a dramatic intellectual turnabout, most archaeologists and other scholars now believe that the earliest Americans followed Pacific Rim shorelines from northeast Asia to Beringia and the Americas," the team writes in the latest study.

"According to the kelp highway hypothesis, deglaciation of the outer coast of North America's Pacific Northwest ~17,000 years ago created a possible dispersal corridor rich in aquatic and terrestrial resources along the Pacific Coast, with productive kelp forest and estuarine ecosystems at sea level and no major geographic barriers."

Over the last few years, more and more evidence has suggested earlier settlements. A 2011 paper found stone tools in Texas that could date back 15,500 years, and petrified human faeces found in Oregon dates back 14,000 years.

A mastodon skeleton was found with a piece of bone from another mastodon in its rib, indicating that humans had hunted it with bone spear points. It dates back 13,800 years. And just last year, a paper was released describing a butchered mastodon in Florida, dating back 14,550 years.

"There is a coalescence of data - genetic, archaeological, and geologic - that support a colonisation around 20,000–15,000 years ago," senior researcher Torben Rick from the US National Museum of Natural History told Seeker.

"This doesn't preclude earlier migrations, or suggest that we should not investigate earlier migrations, but a growing body of evidence is building on intensive research that supports the 20,000–15,000 years ago timeframe, and evidence for earlier migrations is problematic and speculative."

Sea levels have risen since that time, the ocean has eroded the shoreline, and the shorelines have migrated, so evidence of those early migrations is rare, the researchers said.

To find more evidence will require interdisciplinary research focused on regions of the coast that include caves, or that have remained relatively unchanged over the millennia.

Todd Braje of San Diego State University probably described it best.

"Thirty years ago, we thought we had all the answers," he told Seeker. "Now, there are more questions than answers."

The study has been published in Science.