We now know the genetic heritage one of the victims who tragically perished when the Italian city of Pompeii was devastated by a volcanic eruption nearly 2,000 years ago.

Scientists have managed to sequence the genome of a man who was in his mid-life years when he died in the Pompeiian House of the Craftsman, revealing his genetic profile and, fascinatingly, that he had been afflicted by tuberculosis during his lifetime.

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius is considered one of the most devastating volcanic catastrophes in human history. In the year 70 CE, the volcano epically exploded, killing thousands of residents of the nearby cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii, and other settlements.

These victims were either killed by the intense heat of pyroclastic surges the volcano sent tearing through its surroundings, or suffocated by the gas, ash, and pumice that then rained down from the sky.

This manner of death was previously thought to leave DNA from the victims unviable for analysis, since such high temperatures effectively destroy the bone matrix wherein DNA resides.

On the other hand, the ash that covered the victims and preserved their fate for nearly two millennia could have acted as a shield against environmental factors that induce further degradation, such as oxygen.

Previous attempts to analyze the DNA of ancient Pompeiians used polymerase chain reaction techniques, returning short segments of DNA from human and animal victims, and suggesting that at least some genomic information had survived the ravages of the volcano and time.

Recent advances in genome sequencing, however, have dramatically increased the amount of information that can be retrieved from fragments of DNA that would previously have been too damaged to be viable.

In their new study, archaeologist Gabriele Scorrano of the University of Rome in Italy and his colleagues made an attempt to apply these techniques to the remains of two human Vesuvius victims.

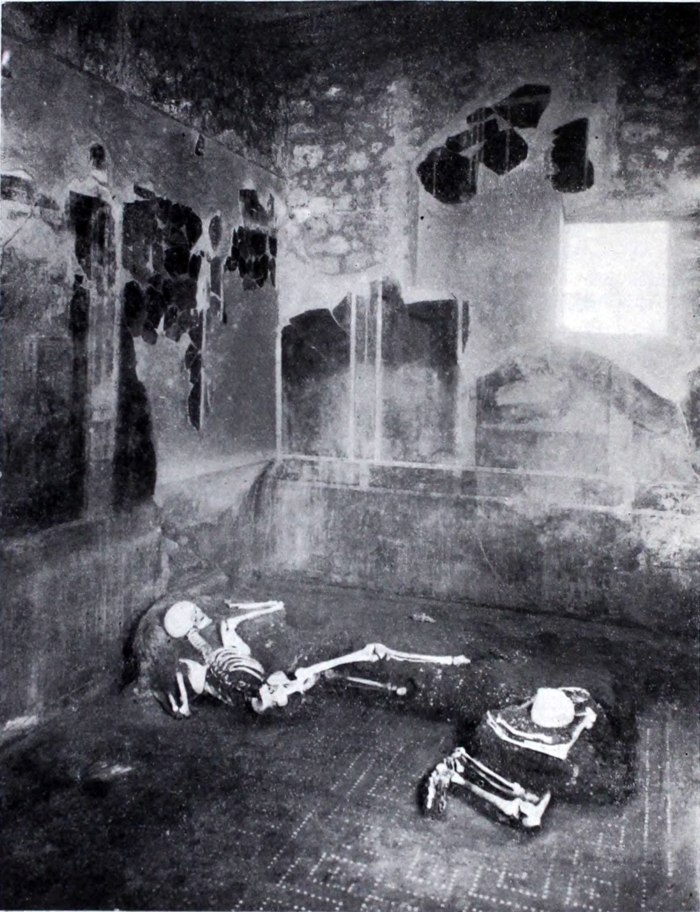

The pair were found in one room of a building now known as the Casa del Fabbro, or House of the Craftsman. The first individual was a man, aged between 35 and 40 years at time of death, who was around 164.3 centimeters (5 feet, 4 inches) tall.

The second individual was a female, over 50 years old when she died, who was around 153.1 centimeters (5 feet) tall. Both these heights are consistent with Roman averages at the time.

(Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, 1934, p. 286, fig. 10.)

(Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, 1934, p. 286, fig. 10.)

Above: The two individuals, laying as they died in the House of the Craftsman.

From these individuals, the researchers extracted DNA from the petrous bone of the skull, one of the densest bones in the body, and therefore among those most likely to retain viable DNA.

Using identical methods, material was extracted and sequenced from both bones. Only the bone of the man, however, yielded sufficient DNA for a reasonable analysis.

The team compared the sample against genomes from 1,030 ancient and 471 modern western Eurasian individuals. The results suggest that the man was Italian, with most of his DNA consistent with people from central Italy, both in ancient and modern times.

However, there were some genes that are not seen in people from the Italian mainland, but are found on the island of Sardinia.

This, the researchers say, suggests that there was a high level of genetic diversity across the Italian Peninsula during the time the man lived.

This makes sense, given how much ancient Romans moved around, and how many slaves they imported from other regions. But the high proportion of genes associated with the Italian population suggests that the man was Italian, not a slave.

Interestingly, the genetic material obtained from his petrous bone showed evidence of the presence of DNA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis – the bacterium that causes tuberculosis. A careful study of his vertebrae suggests that he was afflicted by spinal tuberculosis, a particularly destructive form of the disease.

This is consistent with more-or-less contemporaneous written records from Aulus Cornelius Celsus, Galen, Caelius Aurelianus, and Aretaeus of Cappadocia. The emergence of an urban lifestyle and the subsequent increased population densities during the Roman Empire facilitated the spread of tuberculosis, and it likely wasn't uncommon.

None of these results are necessarily surprising – but the fact that they were obtained at all is incredible, and the breakthrough means we may have a new window into the lives of the Pompeiians, whose deaths were so incredibly striking.

"Our study – albeit limited to one individual – confirms and demonstrates the possibility of applying paleogenomic methods to study human remains from this unique site," the researchers write in their paper.

"Our initial findings provide a foundation to promote an intensive analysis of well-preserved Pompeian individuals. Supported by the enormous amount of archaeological information that has been collected in the past century for the city of Pompeii, their paleogenetic analyses will help us to reconstruct the lifestyle of this fascinating population of the Imperial Roman period."

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.