Before dawn, with just enough light to see by, James Dorey and his colleagues went searching for bees.

This might sound like a futile exercise, since most bees are sleeping rather than finding food when it's dark out; low light dulls the colour of flowers, and night-time produces cooler temperatures.

But at least a few bees have bucked the trend. For the first time ever, Dorey and his Adelaide-based team caught Australia's night foraging bees in the act, and it suggests there's many more night bees hiding under the cover of darkness.

"We know that bees mostly forage during the warm parts of the day – they generally don't like to forage when it's cold, wet, dark, too hot," Dorey, an entomologist at Flinders University, told ScienceAlert.

"Hence, us bee researchers tend to follow a similar work ethic."

We know that some bees are nocturnal, though, having evolved for these types of conditions. So unless scientists go looking for them in the dark, it means we've potentially missed whole species of night bees.

"It has been long thought that some bees might forage at night in Australia, but this was based on pretty circumstantial data," Dorey told ScienceAlert.

"This kind of foraging behaviour has evolved multiple times [around the world] and quite a few bee groups have species that at least extend their foraging into the dark, even if they don't forage in the dark as a full-time gig."

Dorey's excursion to the Daintree rainforest – as well as a number of other research sites around far-North Queensland – ended up proving fruitful, with the team reporting night-time foraging in two native bee species: Reepenia bituberculata and Meroglossa gemmata, the latter a type of masked bee.

It's the first time Australian bees have been recorded foraging in the darkness, and it makes Australia the place with the only known low-light adapted masked bee in the world.

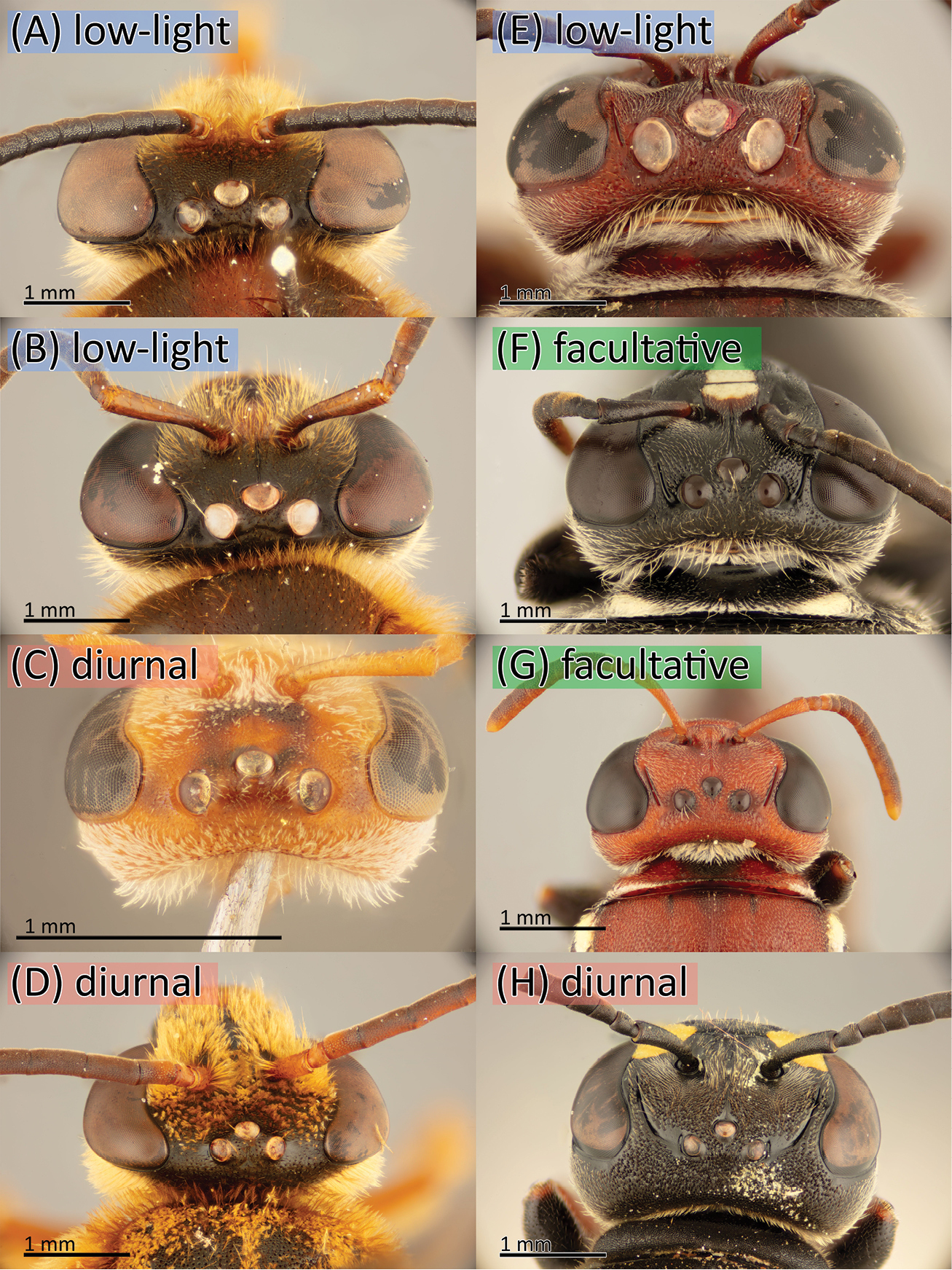

The team went a step further, studyingclose-up images of 75 specimens from 68 bee species, analysing traits such as the type and size of the eyes, head, and body – all to determine if night bees had any physical changes compared to bees that forage during the day.

Bees, like most insects, have both compound eyes (the ones on the side of their head) and simple or ocelli eyes (three smaller eyes in the middle of the head), which only pick up light. Both the compound and ocelli eyes were bigger in bees that foraged in low light.

"We found that these low-light-adapted bees tended to have larger eyes, as well as being on the larger side for bees," Dorey told ScienceAlert.

(Dorey et al., Journal of Hymenoptera Research, 2020)

(Dorey et al., Journal of Hymenoptera Research, 2020)

Above: Low-light, facultative (can forage in both low and regular light) bees, and diurnal (day foraging) bees showing the different ocelli eye sizes. A and B are Reepenia bituberculata, while E is Meroglossa gemmata.

Large eyes make sense – the larger your eyes, the more light you can pick up – and the researchers suggest that larger bodies could help the night bees better thermoregulate their temperature in the chillier conditions.

The team hope that this image-analysis technique can be used in the future to discover other species of night bee, without having to sneak around in the dark hoping to stumble across them.

"We were able to show that it is possible to determine if a bee is adapted to low-light conditions using only imagery," Dorey told ScienceAlert.

"This will make it much easier for researchers to find these neat low-light bees in the future."

With limited research investigating even Australia's day (or diurnal) bee population, there's still a lot more study to be done – including how these creatures might adapt to a warming future, and it's especially important that night bees aren't left behind.

"It is possible that these bees will be threatened by changing climates," Dorey told ScienceAlert.

"But it might be equally possible that they will benefit from warming climates that increase their extents or allow them to forage for longer periods. If the latter is true, then these bees might become more-important for pollination services as foraging windows of diurnal bees become narrower."

The research has been published in the Journal of Hymenoptera Research.