Humans love beer: worldwide, we can go through more than 187.9 million kiloliters (49.6 billion gallons) of it in just one year.

But new research adds this beloved beverage to the long list of products found to contain PFAS (polyfluoroalkyl substances), aka 'forever chemicals'.

PFAS earned that nickname because they don't readily break down in the environment. It's estimated that there are around 12,000 different types of forever chemical, and while health effects are mostly unknown, two in particular – PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid) and PFOS (perfluorooctanesulfonic acid) – are linked to adverse health outcomes, including increased risks of cancer and birth defects.

A team of scientists from the US nonprofit Research Triangle Institute used methods employed by the Environmental Protection Agency to suss out how PFAS gets into beer, and at what levels.

"As an occasional beer drinker myself, I wondered whether PFAS in water supplies was making its way into our pints," says toxicologist Jennifer Hoponick Redmon.

It turns out, quite a lot. The team measured PFAS at levels above the maximum limit set by the EPA, which some argue is still not set high enough to protect people from these chemicals.

While breweries do usually have their own water filtration and treatment systems, these are not necessarily designed to remove PFAS. Up to seven liters of water can be used to make just one liter of beer, and whatever PFAS contaminants are in that water will probably still be there when you crack open your cold one.

The team bought 23 different kinds of beer, each represented by at least five cans, from a North Carolina liquor store in 2021.

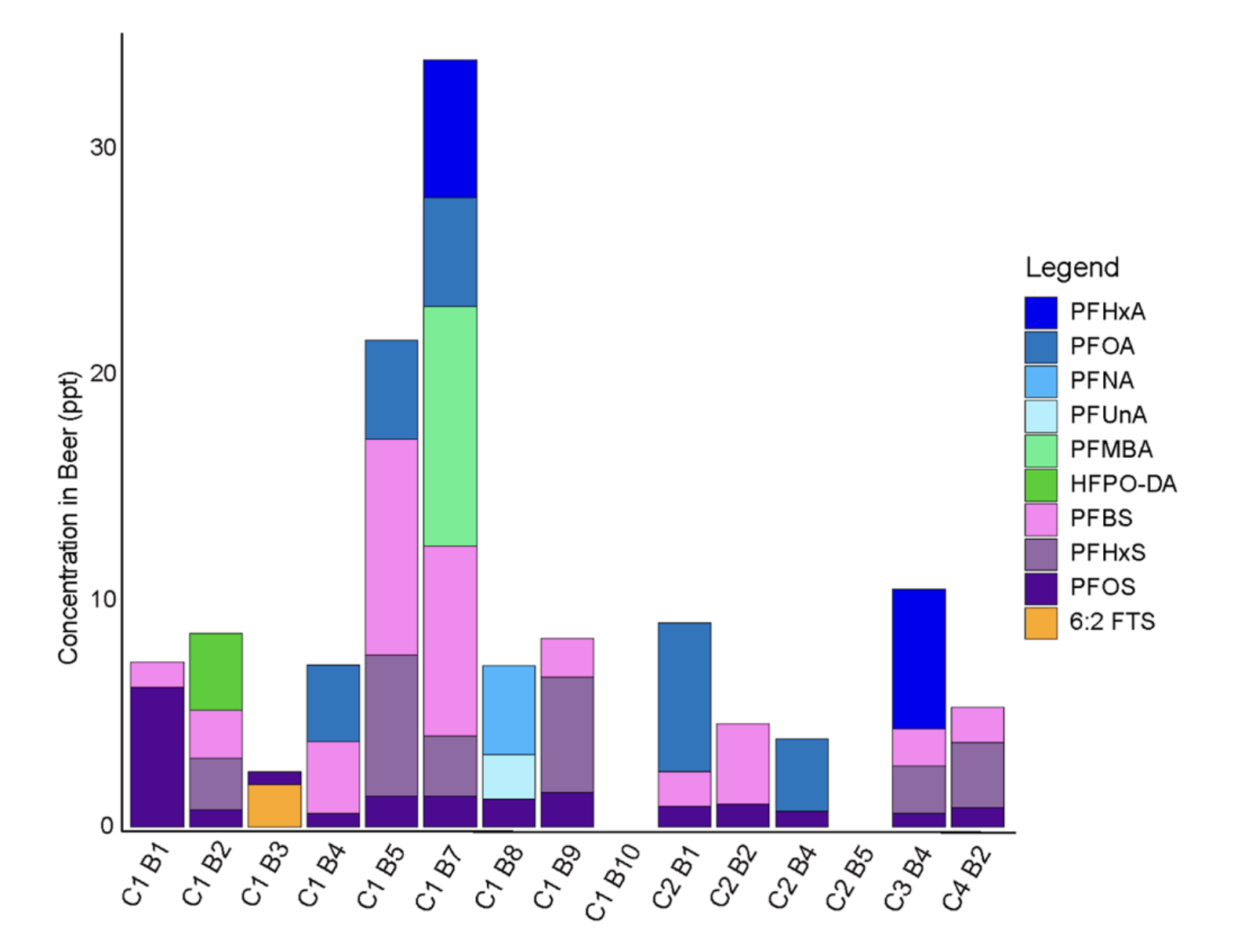

At least one PFAS was found in almost every can they tested. Most contained some level of PFOS. Three beers tested in this study – two from the upper Cape Fear River Basin in North Carolina, and one from Michigan – exceeded the EPA's maximum limit for PFOA concentration, and one beer from the lower Cape Fear River Basin exceeded PFOS limits.

Those limits were developed by the EPA in 2023 for six different kinds of PFAS, and they're designed for drinking water, not beer. But since there's no existing framework for how much PFAS is acceptable in beer – and, like drinking water, beers are intended for direct consumption – Hoponick Redmon's team figured these drinking water standards could be repurposed.

"By adapting EPA Method 533 to analyze PFAS in beers sold in US retail stores, we found that PFAS in beer correlates with the types and concentration of PFAS present in municipal drinking water used in brewing," the team reports.

"North Carolina beers, particularly those within the Cape Fear River Basin, generally had detections of more PFAS species than Michigan or California beers, which reflects the variety of PFAS sources in North Carolina."

PFAS detections and concentrations were particularly elevated in beers brewed in North Carolina, California, and Michigan.

International beers (one from Holland and two from Mexico) were less likely to have detectable PFAS, which may suggest that the countries of origin do not face the same degree of contamination seen in the US.

"Our findings indicate a strong link between PFAS in drinking water and beer, with beers brewed in areas with higher PFAS in local drinking water translating to higher levels of PFAS in beer, showing that drinking water is a primary route of PFAS contamination in beer," the team concludes.

They hope the findings will offer breweries the chance to try to remove PFAS from the water that goes into their beers, and highlight the importance of policy to limit PFAS in general.

This research was published in Environmental Science & Technology.