Even millions of years ago, Australia was a paradise for spiders.

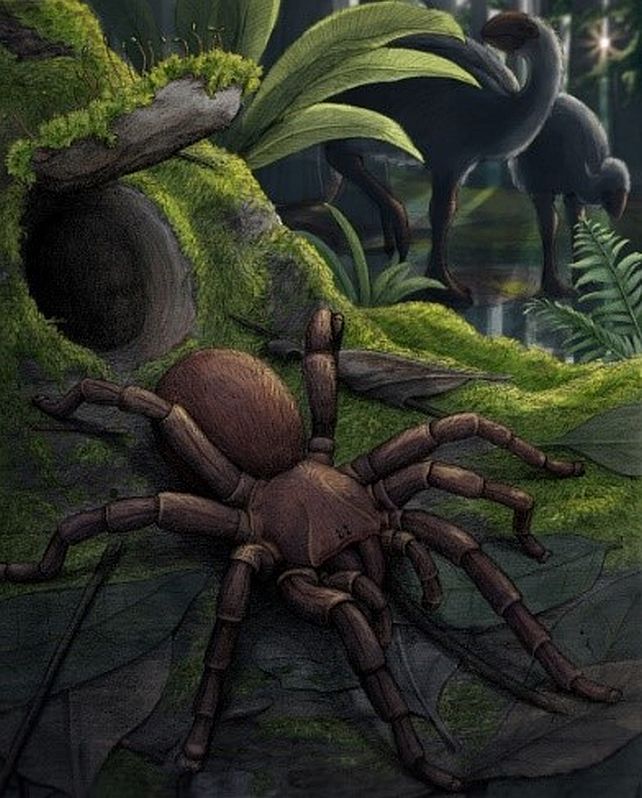

In the arid heart of the continent, scientists have found an exquisitely preserved fossil of a fascinatingly large spider that roamed and hunted in what was once a lush rainforest.

It's not just any fossilized spider, either. It's only the fourth spider fossil ever to be found in Australia, and the first, worldwide, of a spider belonging to the large brush-footed trapdoor spider family, Barychelidae. The new species, which lived in the Miocene 11 to 16 million years ago, has been officially named Megamonodontium mccluskyi.

"Only four spider fossils have ever been found throughout the whole continent, which has made it difficult for scientists to understand their evolutionary history. That is why this discovery is so significant, it reveals new information about the extinction of spiders and fills a gap in our understanding of the past," says palaeontologist Matthew McCurry of the University of New South Wales and the Australian Museum.

"The closest living relative of this fossil now lives in wet forests in Singapore through to Papua New Guinea. This suggests that the group once occupied similar environments in mainland Australia but have subsequently gone extinct as Australia became more arid."

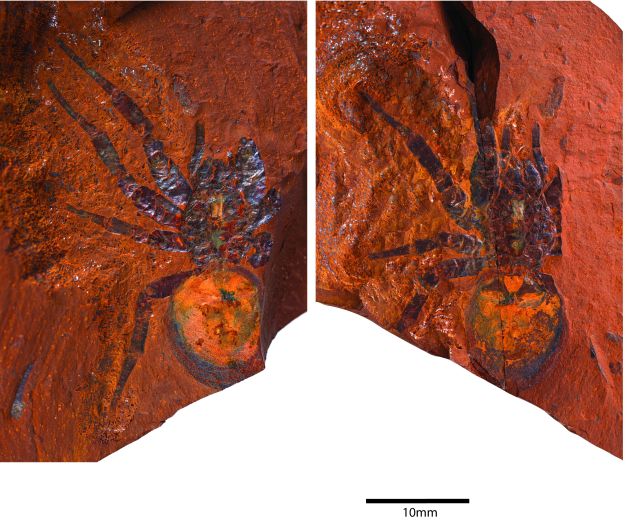

The spider was discovered among a rich assemblage of Miocene fossils, which were found in a grassland region of NSW known as McGraths Flat.

The assemblage is so exceptional that it has been classified as a Lagerstätte – a sedimentary fossil bed that sometimes preserves soft tissues.

In some fossils from McGraths Flat, even subcellular structures can be seen.

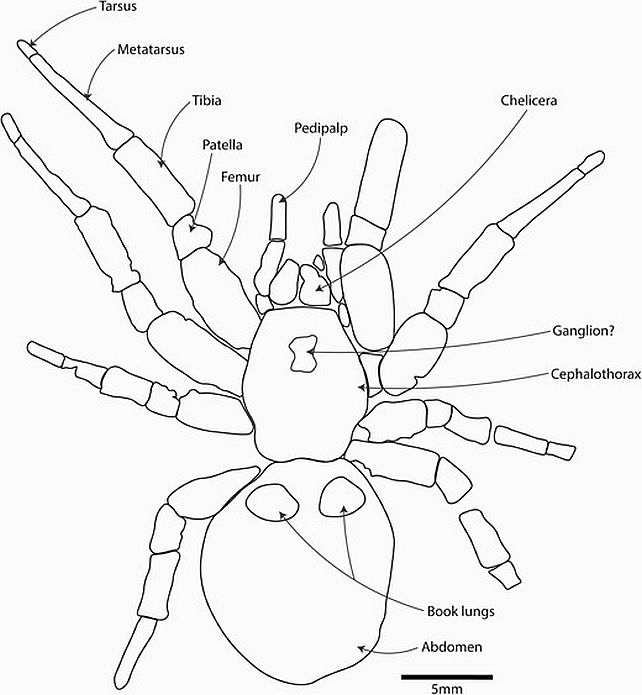

The type of rock found in the fossil bed makes the whole assemblage even more amazing: it's a type of iron-rich rock called goethite, in which exceptional fossils are rarely found. So detailed was the preservation that the researchers could make out minute details in the body of the spider, confidently placing it close to the modern genus of Monodontium – but five times larger in size.

That's not super huge, as Monodontium are usually pretty small, but it's still the second-largest spider fossil ever found, globally. Megamonodontium mccluskyi's body measures 23.31 millimeters, or just under an inch. With its legs spread, it might fit comfortably into the palm of your hand.

The sheer size of the ancient beastie makes the detailed preservation of its physical features all that more impressive.

"Scanning electron microscopy allowed us to study minute details of the claws and setae on the spider's pedipalps, legs and the main body," explains virologist Michael Frese of the University of Canberra, who scanned the fossils using stacking microphotography.

"Setae are hair-like structures that can have a range of functions. They can sense chemicals and vibrations, defend the spider against attackers and even make sounds."

And the discovery might have some clues about how Australia has changed over time, as the landscape dramatically dried out. There are no Monodontium or Megamonodontium spiders living in Australia today, suggesting that aridification during and after the Miocene was responsible for locally wiping out some spider lineages.

We could even learn something about why there are so few trapdoor spiders that have been preserved in the fossil record.

"Not only is it the largest fossilized spider to be found in Australia but it is the first fossil of the family Barychelidae that has been found worldwide," says arachnologist Robert Raven of Queensland Museum.

"There are around 300 species of brush-footed trapdoor spiders alive today, but they don't seem to become fossils very often. This could be because they spend so much time inside burrows and so aren't in the right environment to be fossilized."

The research has been published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.