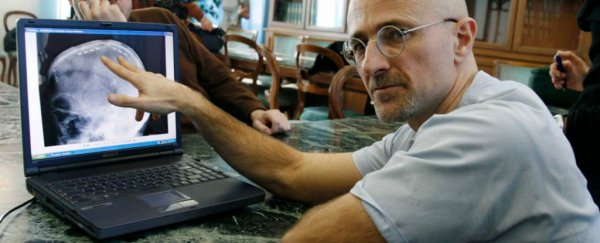

Italian neurosurgeon Sergio Canavero made headlines around the world last year with the bold claim that he'd soon be stitching someone's head onto another person's body. And it looks like he's not the only person with dreams of performing what have been called head transplants, or more appropriately, full-body transplants.

Chinese orthopaedic surgeon Xiaoping Ren of Harbin Medical University recently told The New York Times he was building a team to perform the procedure.

Unlike Canavero, who merely dreamt of the idea, Ren allegedly has plans to carry it out, The Times reports. The operation would happen, he said, "when we are ready".

Nearly two decades ago, Ren was part of a team from the University of Louisville that helped perform the first hand transplant in the US. He spent 16 years in America before returning home to Harbin, China.

The doctor has made headlines previously for doing thousands of head transplants on mice, but the animals lived only a day. Ren told The Times he had also begun practicing on human cadavers but did not give details.

The idea of full-body transplants has been explored by a number of scientists looking to do saving people from deadly diseases, such as spinal muscular atrophy, and extending life. But the challenges of such an endeavour are intense, to say the least.

Here are five of the main obstacles scientists would have to overcome before doing such a transplant:

1. Heads can't stay alive on their own

In any transplant, the donor organ (the one that's been taken from a donor's body) has to be kept alive until it can be placed into the recipient's body.

As soon as an organ gets removed from a body, it begins to die.

For things like heart or kidney transplants, doctors cool the organ to keep it viable for as long as possible. Cooling the organ helps reduce the amount of energy its cells need to stay alive.

Doctors accomplish this by bathing the organ in a solution of cold salt water (saline). This process preserves kidneys for 48 hours, livers for 24 hours, and hearts for about 5 to 10 hours.

But a head would be a far more difficult process.

A head isn't just an isolated organ. It's the heaviest and one of the most complex parts of the body. It houses not just your brain, but also your eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and skin, as well as two separate gland systems: the pituitary, which controls the hormones that circulate throughout the body, and the salivary, which are responsible for producing saliva.

More than a century of disturbing animal research has shown that at the moment of decapitation, blood pressure in the head drops dramatically. The resulting loss of fresh blood and oxygen pushes the brain into a coma, soon followed by death.

This brings us to the next problem.

2. The immune system has to be coaxed into accepting a foreign head

As with any transplant, one of the main issues facing patients is that of their own body: If the immune system flags the foreign organ (or organs, in this case) as foreign, it can unleash a full-scale attack.

What happens in this case is that the immune system of the person receiving the new organ detects immune-triggering substances, called antigens, on the cells of the new organ. These antigens don't match those found on non-foreign organs. This is why almost all transplant patients take immune-suppressing drugs after their procedure.

Because the head is so complex and includes so many organs, the risk of rejection is much higher.

3. The surgery has to happen in under an hour

In a 1970s experiment that would never be allowed today, neurosurgeon Robert White transplanted the head of a monkey onto the body of a donor monkey. He maintained the monkey bodies by cooling them to about 59 degrees Fahrenheit (15 degrees Celsius) for the duration of the procedure.

The monkey with the transplanted head survived until the immune system rejected the head eight days after the surgery, and the monkey died.

One big catch, though: The whole thing has to be done in under an hour, according to White's experiments and Canavero's paper.

Canavero notes in his paper that both of the heads would have to be removed from their bodies at the same time. Working swiftly, the surgeons would have to reattach the head of the person they want to keep alive to the circulatory system of the donor's body while both bodies are under total cardiac arrest. All of this would happen in less than an hour.

Canavero has also come under some fire recently for allegations that his claims are linked with a marketing ploy for a video game. Canavero told Business Insider last week that he has zero involvement with the game and has never heard of the game's producer or his company.

4. Spinal cords are (obviously) incredibly tricky to fuse

In order for the preserved head to be able to communicate with and control its new body, the spinal cord, and the brain must be seamlessly connected, or fused.

This didn't happen with the monkey transplant. While the monkey who's head was transplanted onto a donor body was able to see, move its eyes, and eat, it was paralysed from the neck down.

"The greatest technical hurdle" to a head transplant, Canavero writes in his paper, "is of course the reconnection of the donor's (D)'s and recipients (R)'s spinal cords. It is my contention that the technology only now exists for such linkage."

Canevero's technology is "a special biological glue", he said in a recent TED talk, called polyethylene glycol. In the 1930s and 40s, some experimental surgeons have used this material, which is a type of plastic, to fuse the spinal cords of dogs, but these experiments typically involved attaching a foreign head to the complete body of a dog (artificially giving it two heads), not replacing one dog's head with that of another. These procedures were also done in less than an hour.

After the procedure, one of Canavero's patients would be placed in a coma for up to a month to allow the spinal cords to fuse. Otherwise, the "spaghetti" (as he calls it) that makes up the spinal cord could become gnarled or twisted.

But such a long coma is a potential problem as well, Harry Goldsmith, University of California, Davis professor of neurosurgery, told Popular Science, because medically induced comas often result in infection, blood clots, and reduced brain activity.

5. The procedure has to work in animal trials before being done in humans

Before head transplantation moves into trials in people, all of these problems have to be addressed in animal trials. And there are hurdles to getting animal experiments approved that involve so much cruelty. The bar for approving any such procedure, then, would have to involve proving that it is both helpful and necessary.

So far, there's no evidence that any of this is happening yet, which means any type of surgery approaching this level of risk is decades off, at the least.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: