With the drastic increase in life expectancy seen over the last century or so, it's natural to assume that eventually we'll all be regularly living to 100. But a new study suggests that surge is slowing down.

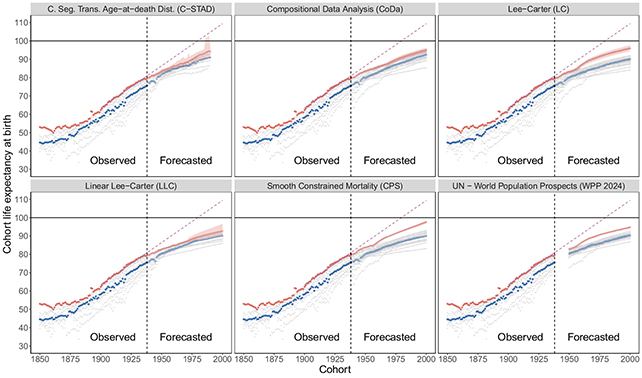

The study comes from an international team of researchers who looked at population data across 23 high-income, low-mortality countries during the 20th century. Historical records were combined with six different forecasting models, primarily for people born between 1939 and 2000.

Here's the takeaway: gains in life expectancy are already slowing down significantly, and that's going to continue for the foreseeable future. Life expectancy will still edge up, but only at a rate about half of what it's been previously.

Related: Misery Is Spiking in One Age Group, Overshadowing The Mid-Life Crisis

It looks like we'll have to adjust our collective and individual expectations accordingly.

"We forecast that those born in 1980 will not live to be 100 on average, and none of the cohorts in our study will reach this milestone," says demographer José Andrade, from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Germany.

"This decline is largely due to the fact that past surges in longevity were driven by remarkable improvements in survival at very young ages."

That significant increase in infant mortality is key to the findings, the researchers say. We've been getting much better at keeping children alive at a younger age, through better medicine and public hygiene, for example, so in well-off countries there's not a massive amount of room for improvement any more.

Looking at historical records, the team found that from 1900 to 1938, life expectancy was rising by about 5.5 months with each generation. For the 1939 to 2000 groups, the increase slowed to around 2.5 to 3.5 months per generation – a noticeable difference.

Life expectancy varies depending on where you are in the world and a whole host of other factors, but for developed nations, it's now hovering around the 80-year mark. That's unlikely to rise very quickly for quite some time.

"In the absence of any major breakthroughs that significantly extend human life, life expectancy would still not match the rapid increases seen in the early 20th century even if adult survival improved twice as fast as we predict," says applied population economist Héctor Pifarré i Arolas, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Being aware of life expectancy is useful in a whole host of ways, whether you're in charge of a nation's healthcare plans or wondering how much to put into your pension. We also know there are myriad ways that lifespan is influenced on the individual level, from the exercise you get to how close you live to the coast.

What this study shows is those influences working out on a much bigger scale – and perhaps pointing to areas where we need to prioritize further research or improve healthcare in order to keep us living longer, happier lives.

"The unprecedented increase in life expectancy we achieved in the first half of the 20th century appears to be a phenomenon we are unlikely to achieve again in the foreseeable future," says Arolas.

The research has been published in PNAS.