Deeps in mines, at the bottom of lakes, and even in your own gut, bacteria are hard at work producing electricity in order to survive in environments low in oxygen.

These potent little power producers have been used in speculative experiments and one day may power everything from batteries to "biohomes".

There are many types of bacteria capable of producing electricity, but some are better at it than others. The trouble with these bacteria is that they are difficult and expensive to grow in a lab setting, slowing down our ability to develop new technologies with them.

A new technique developed by MIT engineers makes sorting and identifying electricity-producing bacteria easier than ever before which may make them more readily available for us in technological applications.

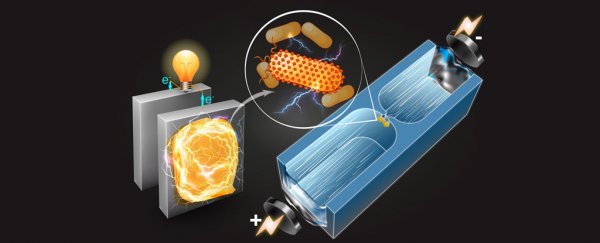

Electricity-producing bacteria are able to pull off the trick by producing electrons within their cells and releasing them through tiny channels in their cell membranes in a process called extracellular electron transfer, or EET.

Current processes for identifying the electricity producing capabilities of bacteria involved measuring the activity of EET proteins but this is a daunting and time consuming process.

Researchers sometimes use a process called dielectrophoresis to separate two kinds of bacteria based on their electrical properties. They can use this process to differentiate between two different kinds of cells, such as cells from a frog and cells from a bird.

But the MIT team's study separated cells based on a much more minute difference, their ability to produce electricity.

By applying small voltages to bacteria strains in an hourglass-shaped microfluidic channel the team was able to separate and measure the different kinds of closely related cells.

By noting the voltage required to manipulate bacteria and recording the cell's size researchers were able to calculate each bacteria's polarizability - how easy it is for a cell to produce electricity in an electric field.

Their study concluded that bacteria with a higher polarizability were also more active electricity producers.

Next the team will begin testing bacteria already thought to be strong candidates for future power production.

If their observations on polarizability hold true for these other bacteria, this new technique could make electricity-producing bacteria more accessible than ever before.

This article was originally published by Futurism. Read the original article.