Some people have genes that make them naturally stronger, according to a largest-of-its-kind study of more than 340,000 people in Finland.

In addition to having a solid foundation for building brawn, individuals with the highest predisposition to hand grip strength were found to have up to 23 percent lower risk of common diseases, and a longer life expectancy.

The study's findings suggest that personalised genetic details on muscle strength and weakness can help doctors identify who is at risk of certain health conditions.

"To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association between a genetic predisposition for muscle strength and various diseases on this scale," says first author Päivi Herranen, a sports scientist from the University of Jyväskylä in Finland.

The team thinks genetic factors that affect muscle strength might play a role in healthy aging. Muscle strength, especially hand grip strength, impacts our ability to manage age-related diseases and injuries, and evidence shows hand grip strength has a strong genetic component.

While this research provides valuable insights, Herranen and colleagues from the University of Jyväskylä and the University of Helsinki emphasize that we need to explore further how lifestyle factors like physical activity interact with genetic predispositions to impact health outcomes.

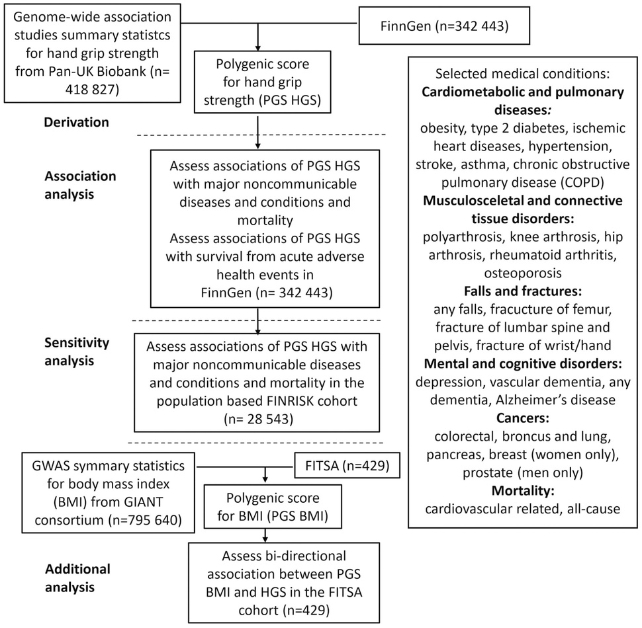

They studied 342,443 people from the FinnGen dataset, an international collaboration of Finnish biobanks that contains health and genetic information. Participants were aged 40 to 108, with women making up 53 percent.

Herranen and team used a recently developed polygenic score (PGS), a single measure that summarizes the estimated effects of hundreds of thousands of genetic variants.

They compared people whose genes predisposed them to stronger or weaker hand grip strength (HGS) and examined how this affected their risk of 27 health outcomes, including mortality and some of Finland's most prevalent non-communicable diseases and conditions.

The diseases and conditions encompassed heart and lung diseases, musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders, cancers, falls and fractures, and mental and cognitive disorders.

They found that a higher polygenic score for hand grip strength (PGS HGS) was associated with a lower risk of death due to cardiovascular causes and a lower risk of death due to any cause, though the effects were small.

People with a higher PGS HGS were also less likely to develop many of the measured conditions. For example, higher PGS HGS was associated with lower depression risk in both sexes, and with lower BMI in women but not men.

The most significant effect was seen in polyarthrosis (a degenerative joint disease) and vascular dementia (dementia caused by restricted blood flow to the brain, often from strokes). Compared to those in the lowest fifth for PGS HGS, those in the highest fifth had a 23 percent lower risk of polyarthrosis and a 21 percent lower risk of vascular dementia.

"Based on our results, muscle strength, cognition functions, and depressive disorders may be partly regulated by the same genetic background," the authors write in their published paper, adding their results "highlight the importance of maintaining adequate muscle strength throughout the lifespan."

The PGS HGS doesn't seem to affect how well we recover from serious adverse health events like ischemic heart disease, stroke, and femur fracture, included in their analysis as the likelihood of death increases in the year following the event.

"It seems that a genetic predisposition for higher muscle strength reflects more on an individual's intrinsic ability to resist and protect oneself against pathological changes that occur during aging than the ability to recover or completely bounce back after severe adversity," Herranen explains.

The team suggests that using the PGS HGS alone isn't likely useful in clinical settings. However, it could be valuable for future research to discover whether the link between muscle strength and health issues is due to direct causes or shared genetic and environmental factors.

"It could be used to study how lifestyle, such as physical activity, modifies human intrinsic capacity to resist diseases and whether their impact on health differs due to genetic predisposition for muscle strength," the researchers conclude.

"Further research is also needed to determine whether an individual's genetic predisposition for muscle strength affects exercise responses and trainability."

The research has been published in The Journals of Gerontology: Series A.