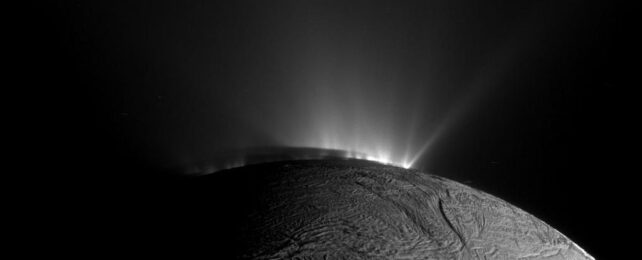

Since the Cassini spacecraft discovered plumes of water vapor erupting from geysers on Enceladus nearly 20 years ago, Saturn's ice-covered ocean moon has been a hot topic.

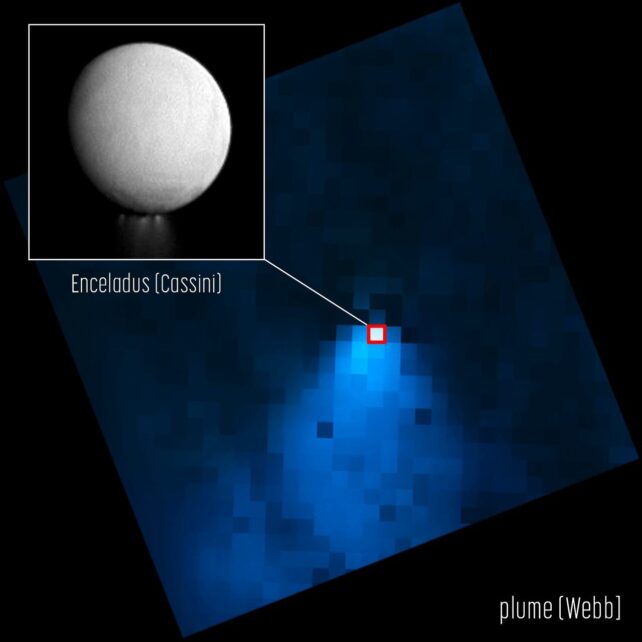

The James Webb Space Telescope has now caught sight of the largest plume yet. The telescope's astonishingly sensitive eye measured an eruption of water vapor punching at least 10,000 kilometers (over 6,000 miles) out into space. That's around 20 times the size of Enceladus itself, and it has given scientists an unprecedented glimpse at how the moon's geysers supply material to Saturn's icy rings.

"When I was looking at the data, at first, I was thinking I had to be wrong, it was just so shocking to map a plume more than 20 times the diameter of the moon," says planetary scientist Geronimo Villanueva of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

"The plume extends far beyond what we could have imagined."

The geysers Cassini detected in 2005 changed everything we thought about the cold moon: They were proof that Enceladus wasn't a solid, frozen ball, as previously thought, that under its shell of thick ice lurks a global liquid ocean, kept liquid by the heat created by the constant push-pull of its gravitational interaction with Saturn.

And where there is liquid water, there may be life.

That's still an open question since getting through kilometers of ice on an alien world to look for what might be no more than microbes is not exactly simple. But Enceladus is intriguing for other reasons, too – not least of which is its contribution to Saturn's ring system.

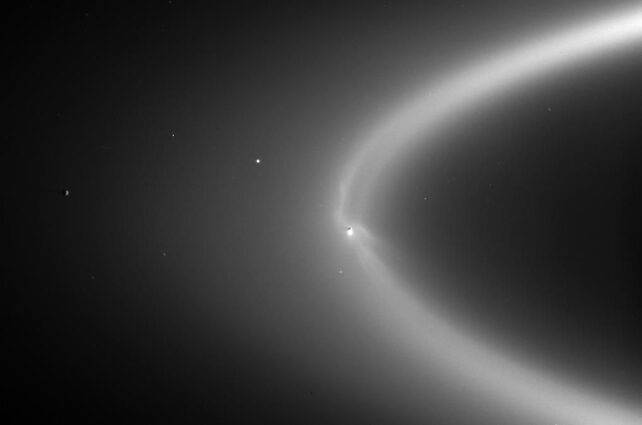

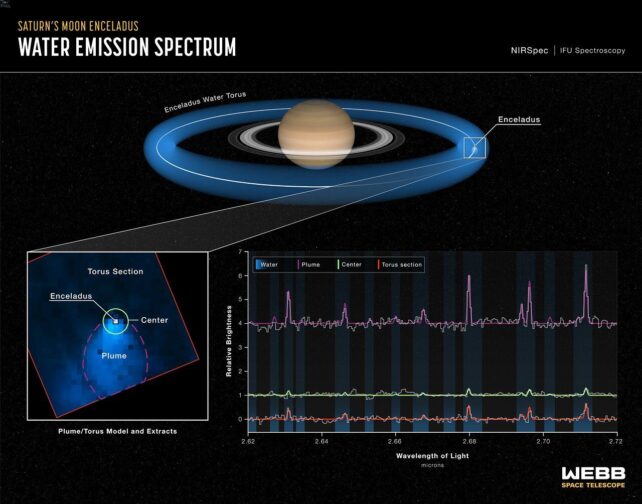

In 2011, scientists using the Herschel infrared observatory discovered that Enceladus isn't just actively spewing water out randomly into space. Its geysers generate a diffuse and fuzzy donut-shaped ring, or torus, of microscopic frozen particles, mostly water ice, with some traces of silicates, carbon dioxide, and ammonia. It's centered around the same location as Saturn's E ring, the second-outermost of Saturn's rings, and Enceladus's orbit.

"The orbit of Enceladus around Saturn is relatively quick, just 33 hours. As it whips around Saturn, the moon and its jets are basically spitting off water, leaving a halo, almost like a donut, in its wake," Villanueva explains. "In the Webb observations, not only was the plume huge, but there was just water absolutely everywhere."

Water vapor is hard to find in space because it tends to be transparent at most wavelengths. In infrared, however, water vapor fluoresces, and that's why the infrared Herschel observatory could detect the torus in 2011. The JWST is an infrared telescope that is significantly more powerful than Herschel.

In November 2022, the JWST collected just 4.5 minutes' worth of data on Enceladus. That was sufficient to capture the largest plume anyone had ever seen erupting from the moon – providing direct evidence for how the plumes feed into the torus.

Based on this data, the team could ascertain the plume's ejection rate. At the time of the observations, Enceladus was spewing out water vapor at 300 liters (79 gallons) per second. That's roughly two bathtubs' worth of water. Imagine the water pressure required to fill your bathtub in half a second. You probably wouldn't have a bathtub after that.

The researchers also calculated that roughly 30 percent of the water vapor would stay in the torus. The remaining 70 percent supplies the rest of the Saturn system, including the icy rings and Saturn's upper atmosphere.

Sadly, it seems the plumes are probably too diffuse to detect possible molecular signs of life that scientists hoped might be collected by flying through them. But this helps narrow down where and how to look for biomolecules when astrobiology missions reach the icy moon.

And, on the surface of Enceladus, the team detected something that could be cyanide compounds. Although cyanide is poisonous, it could have played a key role in the emergence of life on Earth, and if it is on the surface of Enceladus, its presence would be very intriguing.

In its second round of observations, JWST will return to Enceladus for a longer look. Scientists hope this will yield more clues about the possibility of life on Enceladus. In particular, the researchers will look for hydrogen peroxide, a biomolecule with a wide range of functions.

"Enceladus is one of the most dynamic objects in the Solar System and is a prime target in humanity's search for life beyond Earth," says geochemist Christopher Glein of the Southwest Research Institute.

"In the years since NASA's Cassini spacecraft first looked at Enceladus, we never cease to be amazed by what we find is happening on this extraordinary moon."

The research has been accepted into Nature Astronomy, and a preprint is available via the NASA website.