In the end, the Chinese space station Tiangong-1's crash back into Earth's atmosphere was exactly what anyone could have hoped for.

The station's fiery reentry was close to where scientists would have tried to direct it if they'd had any control over the spacecraft's return.

But for a long time, the exact return point was closely followed.

Most space debris burns up in the atmosphere, which is fortunate for us, as there's so much debris there. But this spacecraft was large and multilayered enough that it was possible at least some segments or parts would survive the reentry.

Still, the chance that any bit of space station would hit a person was always infinitesimal - about "1 million times smaller than the odds of winning the Powerball jackpot," the Aerospace Corporation, a nonprofit spaceflight-research company, wrote before the reentry.

"It's not impossible, but since the beginning of the space age… a woman who was brushed on the shoulder in Oklahoma is the only one we're aware of who's been touched by a piece of space debris," Bill Ailor, an aerospace engineer with the Aerospace Corporation who specialises in atmospheric reentry, previously told Business Insider.

Chances were always that if anything did survive the fall, it would land in the ocean. After all, oceans cover 71 percent of Earth's surface, so, statistically, that would be the safest place for something to end up.

And that's what happened.

At approximately 00:16 UTC on Sunday, Tiangong-1's orbit finally decayed enough that it got caught up in the thicker air surrounding our planet.

The "vast majority" of the 34-foot (10-metre), 9.4-ton, school-bus-size spacecraft burned up in the atmosphere, China's space agency said in a statement, according to Reuters.

But some material from the craft most likely survived, Brad Tucker, an astrophysicist with the Australian National University, told the news outlet.

That material seems to have ended up in the largest ocean on the planet, the Pacific, not all that far from the "spacecraft graveyard" where scientists try to de-orbit large spacecraft so they crash back to Earth safely, the astronomer Jonathan McDowell said on Twitter.

NW of Tahiti - it managed to miss the 'spacecraft graveyard' which is further south! pic.twitter.com/Sj4e42O7Dc

— Jonathan McDowell (@planet4589) April 2, 2018

"Most likely the debris is in the ocean, and even if people stumbled over it, it would just look like rubbish in the ocean and be spread over a huge area of thousands of square kilometers," Tucker said.

From launch to crash

China launched Tiangong-1, which translates to "Heavenly Palace" in English, into orbit on September 30, 2011. Space experts lauded it as an important achievement.

The station was a stepping stone for the Chinese space program, used to practice docking maneuvers in space – something essential for further space exploration, including the use of larger space stations in the future.

Tiangong-1 also served as a prototype for a larger and more permanent 20-ton station: the Chinese large modular space station that China expects could be operational in 2022.

Tiangong-1 was visited by two crews of taikonauts, or Chinese astronauts. The first was a three-person crew in June 2012 that included the first Chinese woman in space; the second was another three-person crew in June 2013.

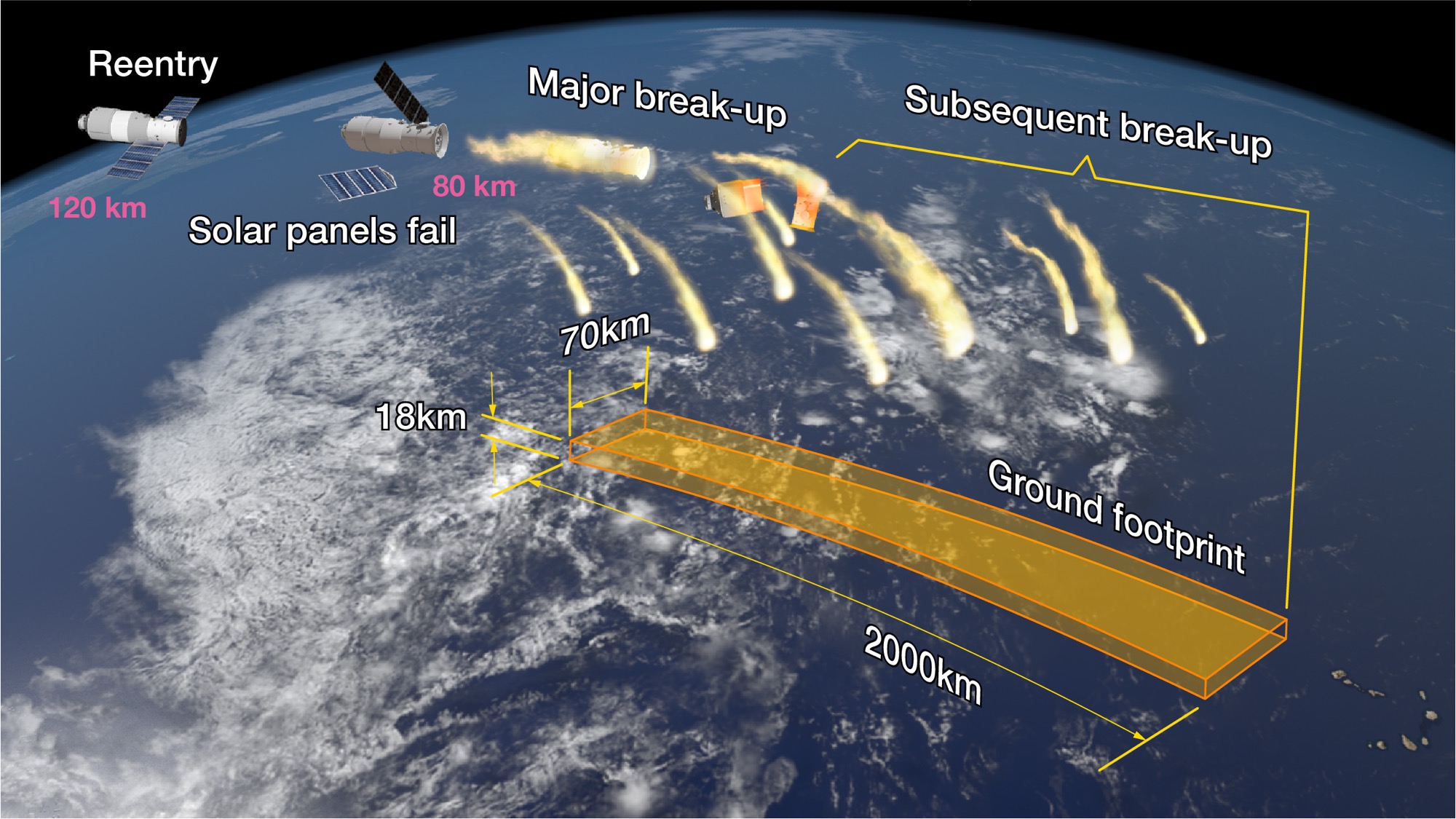

An illustration of Tiangong-1 crash. (Aerospace Corporation)

An illustration of Tiangong-1 crash. (Aerospace Corporation)

All in all, the station "conducted six successive rendezvous and dockings with spacecraft Shenzhou-8, Shenzhou-9, and Shenzhou-10 and completed all assigned missions, making important contributions to China's manned space exploration activities," said a memo China submitted in May to the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space.

No visitors arrived at Tiangong-1 after that second crew, but the station still gathered data and observed Earth's surface, monitoring ocean and forest use, according to Space.com.

In early 2016, China lost contact with Tiangong-1. In September of that year, China launched a Tiangong-2, which a crew visited the next month.

Since the loss of contact, Tiangong-1's orbit slowly decayed. Objects in low Earth orbit need the occasional boost to maintain their orbit - otherwise, those orbits eventually decay until the objects hit Earth's atmosphere.

When Tiangong-1 hit the atmosphere, it was most likely travelling at about 17,000 mph (27,400 km/h).

But it would have been a sudden stop, as moving that quickly into thicker air is a recipe for a fireball. It's likely that the drag would have quickly ripped off solar panels and antenna. Superheated plasma would have melted and disintegrated much of what was left.

And finally, a rain of whatever remained sprinkled the South Pacific, northwest of Tahiti and fairly close to Samoa.

It wasn't the largest object to fall back to Earth - and with more than 14,000 uncontrolled pieces of space junk larger than a softball flying around the planet, it won't be the last.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: