Public health officials and business leaders like Bill Gates have long warned that the world is not ready for the next pandemic.

Now an initiative led by Tom Frieden, former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has developed a tool that spotlights gaps in preparedness, and actions that countries and organizations can take to close them.

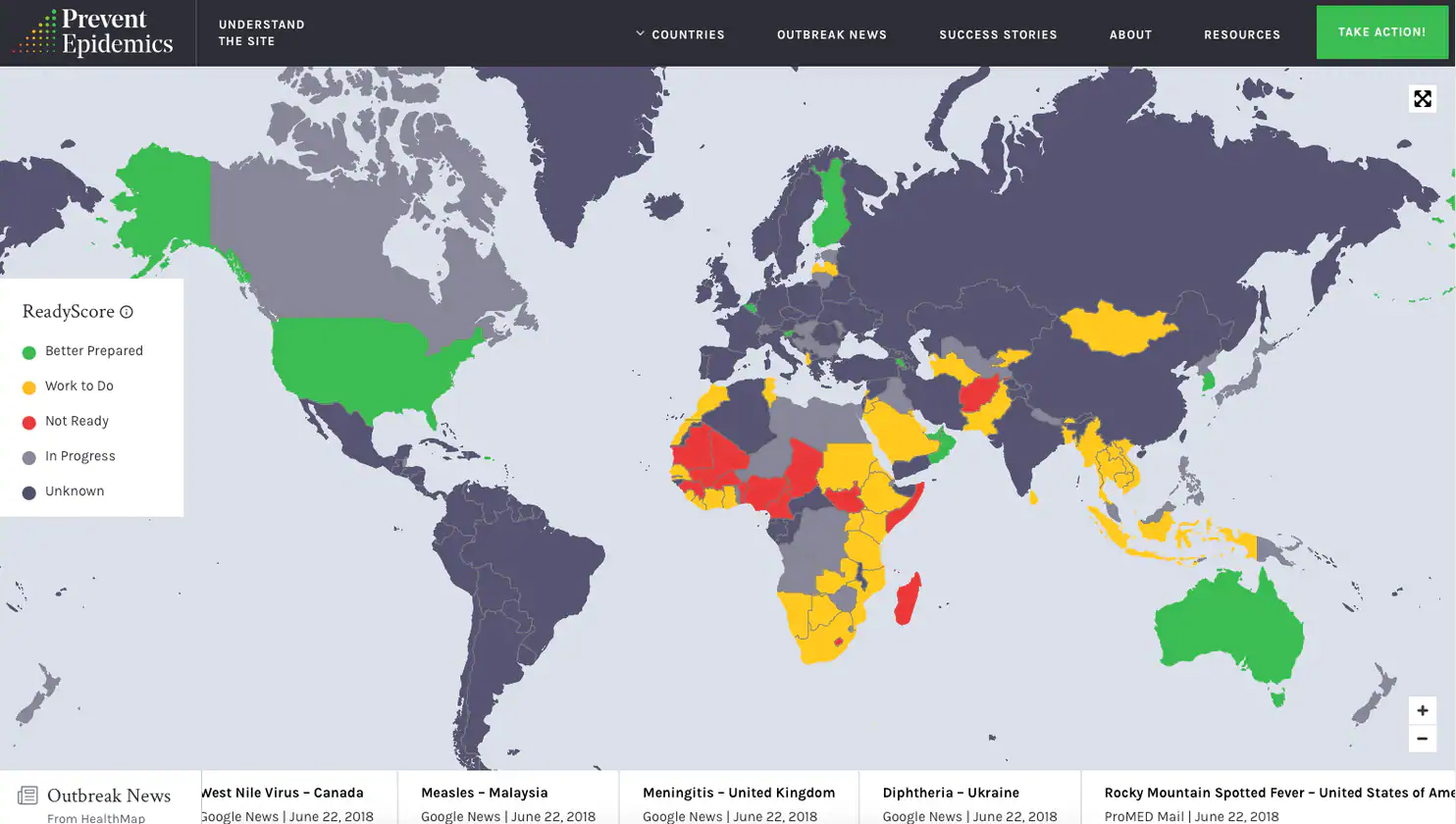

The new website, PreventEpidemics.org, gives an individual score to each country and uses color codes to rank the world by five levels of preparedness.

"What this does, it tells you where the gaps are and what needs to be done," said Frieden, chief executive of Resolve to Save Lives, part of Vital Strategies, a New York-based public health nonprofit organization.

Infectious diseases can spread from one village to any country in the world in about 36 hours. On average, there are 100 outbreaks a day around the world.

But the website shows that most countries have not yet taken the steps needed to prepare for this risk.

Gaps include a lack of monitoring systems that can spot unusual health reports from local clinics, or insufficient trained disease detectives who can rapidly deploy when a new health threat is reported.

The score, from 0 to 100, is based on existing data from evaluations of epidemic preparedness developed by the World Health Organization after the 2014 Ebola epidemic. Those evaluations have been going on since 2016, but the data contained in them, while public, is difficult to find.

Independent and regular monitoring and tracking for epidemic and pandemic risk is key to keeping biological threats on the agenda of global political leaders, experts say.

Tom Inglesby, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, said the tool "shines a more clear light" on the results of those evaluations in a way that can "help sustain the attention of political leaders and donors."

The identified gaps will be easy for donors to understand and to address, he said.

Global health officials say it's more important than ever for disease outbreaks to be stopped at their source before they become full-blown epidemics.

In the United States, many experts are worried about the Trump administration's commitment to maintaining strong levels of funding for CDC's efforts to fight infectious disease threats as part of its global health security initiative.

Only 430 million people, or 6 percent of the world's population, live in the countries that are considered better prepared to prevent epidemics, according to their scores. (They include Australia, Belgium, Finland, Oman, South Korea, Slovenia, the United Arab Emirates and the United States.)

(PreventEpidemics.org)

(PreventEpidemics.org)

While those countries, highlighted in green, have scores above 80, not a single country has completed all the steps that are recommended, including making a plan to address gaps in funding and implementing the plan.

But more than 60 percent of countries, representing nearly 5 billion people, have not volunteered to conduct these epidemic preparedness evaluations, including most of Europe, Russia, China, India and virtually all of South America.

Of all continents, Africa leads the world in terms of the number of countries that have completed these evaluations. But most of those countries, highlighted in red and yellow on the PreventEpidemics website, are not ready (red), or have work to do (yellow), to prepare for the next epidemic.

Light gray means an evaluation is in progress, with no data available; and dark gray is unknown.

By the end of the year, 100 countries will have gone through this rigorous evaluation, which Frieden said is a real accomplishment and indicates the commitment of countries to improve.

"Progress assessing those gaps has been excellent," he said. "Progress fixing them, not so good."

The website is being presented Friday at the annual Aspen Ideas Spotlight Health Festival.

Nigeria, which has been battling outbreaks of yellow fever, monkey pox and Lassa virus, which can cause a lethal hemorrhagic fever resembling Ebola, is one of the countries identified by PreventEpidemics as not ready.

Frieden's group is helping Nigeria improve its disease surveillance by providing laptops and staff to the health ministry so its detection team gets better data.

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.