Don't you just hate it when you discover bits of yourself that seem to have a mind of their own? Like when you decide you really don't want to like someone, but some other part of you does anyway.

Well, bad news for all you fellow egg-bearers out there - turns out our ova make their own such 'choices', too.

After all that time and effort agonising over whether a potential partner even likes you, then trying to decide if they're the right person to take on the massive endeavour of parenthood with, your eggs can basically turn around and say "yeah, nah".

"The idea that eggs are choosing sperm is really novel in human fertility," said clinical embryologist Daniel Brison from Manchester University in the UK.

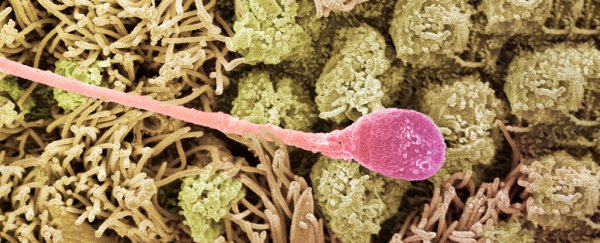

But that appears to be exactly what happens, researchers from Stockholm University and Manchester University found, by testing the reactions of sperm to the follicular fluid that surrounds human eggs.

Human eggs release compounds called chemoattractants into this fluid, which chemically communicates with sperm. While the exact chemicals are yet to be identified (some researchers suspect progesterone is involved), whatever it is can trigger sperm to change swimming directions.

The researchers exposed sperm to follicular fluid from two females (a partner and a non-partner) and observed where the sperm accumulated.

Because sperm can't be exposed to follicular fluid from two different people at once in natural circumstances, the team also tested sperm with two follicular fluids consecutively. All up, the researchers tested sperm and follicular fluid from 60 couples undergoing reproductive treatments.

"Follicular fluid from different females consistently and differentially attracts sperm from specific males," the team wrote in their paper, finding that eggs attracted between 18 to 40 percent more sperm from their preferred males.

And the eggs did not always agree with their owner's choice of partner: the likelihood of eggs attracting sperm from other males was no different from the likelihood eggs would attract the actual partner's sperm.

But how do we know it's not the sperm doing the choosing? One of the researchers, zoologist John Fitzpatrick from Stockholm University, explains that it doesn't make sense for sperm to be the picky one, as sacrificing the swimmers doesn't cost males much.

"But for eggs, and women, there are a lot of extra costs that come after fertilisation such as the costs of pregnancy," Fitzpatrick told Inverse. "Because of these costs, eggs should be choosy about which sperm fertilise them."

Biologists call this phenomenon cryptic female choice and it is well known in other species - particularly those with external fertilisation, like mussels. It makes sense in these types of animals because they release their gametes (eggs and sperm) into the wide open ocean without making any previous choices on who they'll mate with - so it's up to the eggs to perform the only quality control checks.

Scientists have also found that mouse IVF eggs prefer sperm from less related males. But this is the first example of human egg preferences, so the reasons and mechanisms behind it are still up for discovery.

The team cautions that some of the experiment's conditions could affect the accuracy of the results. For example, the IVF eggs they used had been through treatments that may have changed some biological processes.

Also, the concentrations of sperm were much higher than natural (20,000 sperm per egg instead of the average of around 250) and they were placed quite close to the egg - which may minimise differences in the effects of chemoattractants.

"Research on the way eggs and sperm interact will advance fertility treatments and may eventually help us understand some of the currently 'unexplained' causes of infertility in couples," Brosin concluded.

Further down the line, once we know that an egg and sperm are not happy with each other, there might be a way to convince them our choice of partner is the right one after all.

This research was published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.