We may be a step closer to being able to breathe through our butts. A new human clinical trial has shown that it's safe, at least, to deliver oxygen rectally.

It sounds like a joke – and indeed, the research that led to this trial won an IgNobel prize for physiology last year – but there's a good reason behind it. If proven effective, it could become a backup (pun not intended) method for providing oxygen to patients with blocked airways.

The work isn't entirely without precedent. Animals like pigs, rodents, turtles, and some fish are known to be capable of butt-chugging oxygen when the need arises.

Related: Pouring Coffee Into Your Rectum Isn't Worth The Risk, Says Expert

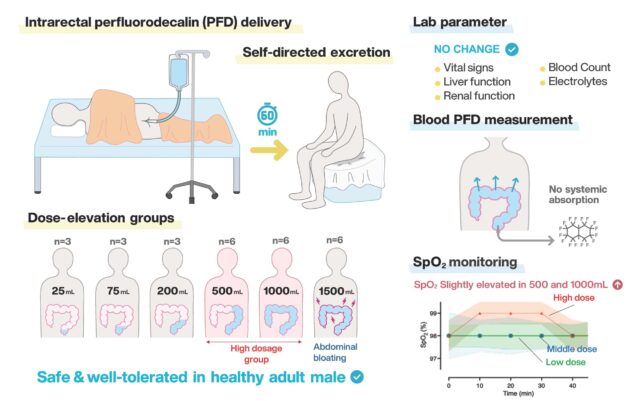

The process is called "enteral ventilation", and researchers envisage that in the case of humans, it would involve delivering a perfluorocarbon liquid containing a very high concentration of oxygen directly into the rectum. The idea is that the oxygen passes through the intestinal walls and makes its way into the bloodstream, bypassing any issues a patient may have breathing the more traditional way.

This first clinical trial wasn't testing how well the method worked – it just focused on whether it was safe. To that end, 27 healthy male volunteers in Japan were tasked with holding between 25 and 1,500 milliliters of a non-oxygenated version of the liquid in their rectum for 60 minutes.

No serious adverse effects were reported, although participants taking the highest volumes did feel some abdominal bloating, discomfort, and pain. Other vital signs remained unchanged, and only seven participants weren't able to hold their 'breath' for the full hour.

"This is the first human data, and the results are limited solely to demonstrating the safety of the procedure and not its effectiveness," says Takanori Takebe, biomedical scientist at the University of Osaka.

"But now that we have established tolerance, the next step will be to evaluate how effective the process is for delivering oxygen to the bloodstream."

The next trial will use the properly oxygenated version of the liquid and test how much and for how long it needs to be held within to clinically improve a patient's blood oxygen levels.

The research was published in the journal Med.