It might look like a regular patch of Sun, but what you are looking at in the image above is a sight humanity has never seen before.

It's actually the Sun's south pole, and our first-ever glimpse of this region comes courtesy of a daredevil maneuver by Solar Orbiter, which plunged below the plane of the Solar System to catch an oblique glimpse of a part of the Sun usually hidden from view.

"Today we reveal humankind's first-ever views of the Sun's pole," says astrophysicist Carole Mundell, director of science of the European Space Agency (ESA).

"The Sun is our nearest star, giver of life, and potential disruptor of modern space and ground power systems, so it is imperative that we understand how it works and learn to predict its behavior. These new unique views from our Solar Orbiter mission are the beginning of a new era of solar science."

The poles of the Sun have long been a white whale for solar physics. Like the other planets in the Solar System, Earth orbits more or less around the Sun's equator. So, too, has most of our solar instruments. This means that we've never had a clear view of the top and bottom of our star.

It's a problem for many reasons, not least of which is that, every 11 years, those poles flip, and north and south polarity reverses. We don't have a good handle on why this process happens. A good, clear view of the poles would give a lot of new information that scientists could use to help figure it out.

Solar Orbiter has just made the best effort yet to obtain that clear view. It's the perfect timing for this observation, too: the Sun is emerging from solar maximum, the period during which that polar flip takes place. In February 2025, the spacecraft, usually zipping around the Sun's middle, tilted its orbit by 17 degrees – enough to finally see the pole.

Previous orbiters had only ever tilted their orbits as far as 7 degrees, with the exception of the Ulysses orbiter that, alas, carried no imaging equipment as it made three exciting loops directly over the Sun's poles between 1994 and 2008.

"We didn't know what exactly to expect from these first observations," says astrophysicist Sami Solanki of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System research in Germany. "The Sun's poles are literally terra incognita."

Three imaging instruments took detailed readings of the solar south pole over the days' worth of observations:

- The Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) probed the magnetic fields of the Sun as manifested by the polarization of its light;

- the Extreme-Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) took observations in the specified wavelengths to capture fine structures in the solar atmosphere;

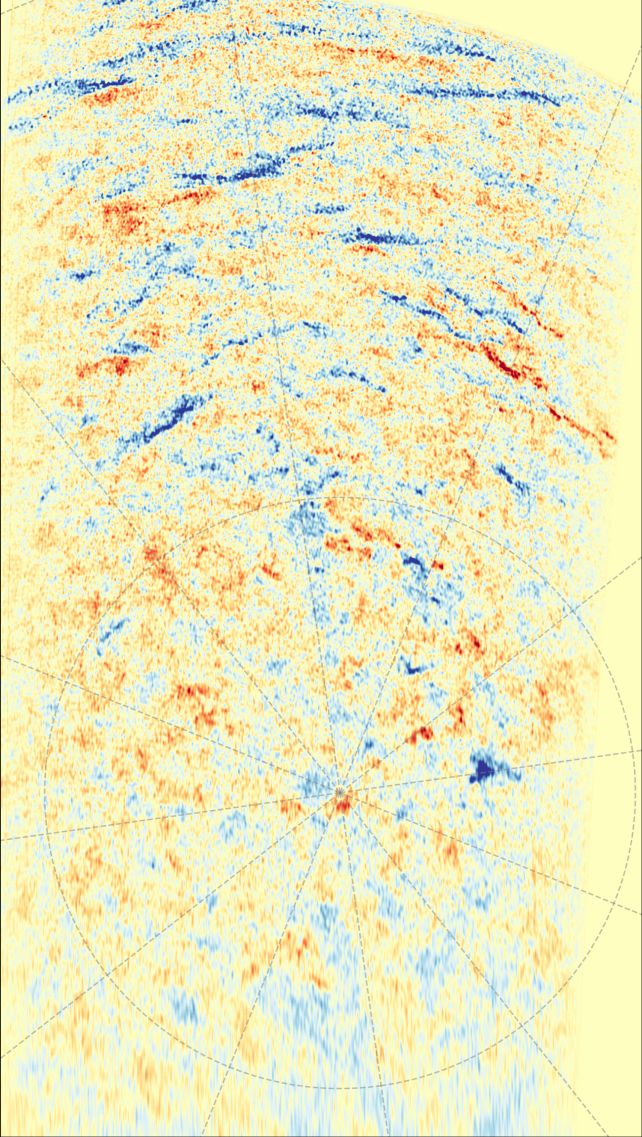

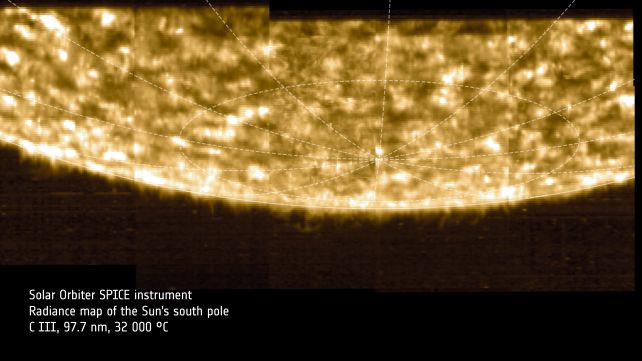

- and the Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE) instrument captures observations in ultraviolet and extreme ultraviolet to probe the temperature and composition of the solar corona.

The magnetic field at the south pole was a bit of a fascinating mess during Solar Orbiter's observation period, with a mixture of both north and south polarities.

As the polar flip settles down, one polarity will strengthen and the other wane, all the way to solar minimum, when the magnetic field will be at its most orderly before starting to fray again.

Meanwhile, SPICE tracked the motion of carbon ions in the region of the solar corona known as the transition region, where the temperature rapidly spikes by thousands of degrees. The radiance map reveals how the ions are distributed, while the doppler map shows how fast the ions were moving away from or towards Solar Orbiter at the time of observation.

How particles move around in the solar atmosphere is crucial to understanding the solar wind – the constant stream of charged particles that blows from the Sun out into the Solar System.

In just a short time, the spacecraft captured enough data to keep solar scientists busy for years to come. That data, however, is just the beginning. Solar Orbiter is going to continue orbiting the Sun at a 17-degree tilt until December 2026, when it will kick things up a notch to 24 degrees. It will then ramp up to 33 degrees in June 2029.

"This is just the first step of Solar Orbiter's 'stairway to heaven'," says ESA astronomer Daniel Müller.

"In the coming years, the spacecraft will climb further out of the ecliptic plane for ever better views of the Sun's polar regions. These data will transform our understanding of the Sun's magnetic field, the solar wind, and solar activity."