New footage has revealed Antarctica's Thwaites Glacier is shrinking from below in a way scientists hadn't expected – with melting happening rapidly along the cracks and crevasses in its base.

Though the ice loss is slower than predicted in other sections, the 130 kilometer (80 mile) wide, Florida-sized glacier could still contribute more than 65 centimeters (25 inches) of sea-level rise as it thaws over the next century or so – earning it the nickname the 'Doomsday Glacier'.

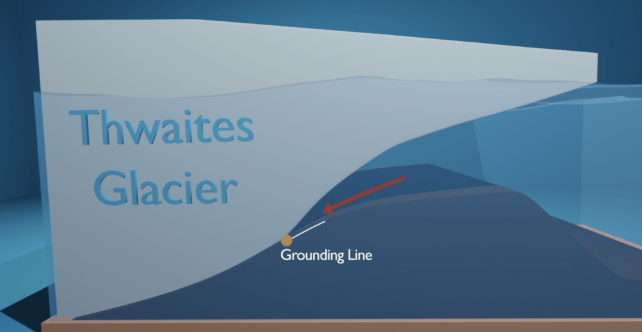

The point where the glacier meets the ocean and the seafloor, known as the 'grounding line', has already retreated 14 kilometers [8.7 miles] since the '90s and the amount of ice flowing out of the region has nearly doubled.

But exactly how melting happens at that grounding line hasn't been fully understood until now.

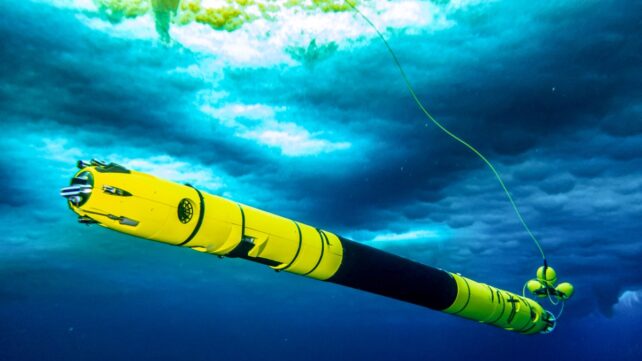

Using a mix of remote sensing and underwater footage captured by a robot, a team of researchers from the US and UK were able to directly observe the process beneath the Thwaites Glacier for the first time.

The footage, as you can see below, is as hypnotizing as it is worrying.

They observed the flat topography beneath the glacier melting slower than expected, thanks to a layer of fresher water between the bottom of the ice shelf and the warmer ocean below.

More surprisingly, the researchers saw warm water had formed terrace-like structures in the ice shelf's base. And in these areas, as well as cracks, melting was happening faster than expected.

Here's footage of the Icefin robot that captured the footage being lowered down a 600-meter (almost 2,000-foot) long borehole. Located around 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) from the Thwaites Glacier grounding line, the hole was drilled in the ice back in 2019.

The results of the multidisciplinary study have been published across two studies in Nature this week.

"These new ways of observing the glacier allow us to understand that it's not just how much melting is happening, but how and where it is happening that matters in these very warm parts of Antarctica," said earth scientist Britney Schmidt from Cornell University, who is lead author on one of the Nature papers.

"Warm water is getting into the weakest parts of the glacier and making it worse," Schmidt told Reuters in an interview.

"That is the kind of thing we should all be very concerned about."

Screenshot of an animation showing the Thwaites Glacier's grounding line and how it's retreating as warm ocean water melts the ice. (International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration)The hope is that the more we understand about how the 'Doomsday Glacier' is melting, the better placed we'll be to help mitigate the impacts of climate change and the resulting sea-level rise.

In addition to the footage, the team used the borehole mentioned above to take samples, which were compared with data from five other sites beneath the ice shelf.

Over nine months of observations, the water near the grounding line became warmer and saltier, but the melt rate remained steady at around 2 to 5 meters per year – less than computer models had predicted.

The team then put Icefin through the borehole and spotted the staircase-like terraces and cracks, or crevasses.

Crevasses have also been seen progressing along the surface of the glacier, leading scientists to predict they could one day play an important role in the glacier's collapse.

"Our results are a surprise but the glacier is still in trouble," says Peter Davis, an oceanographer with the British Antarctic Survey.

"If an ice shelf and a glacier are in balance, the ice coming off the continent will match the amount of ice being lost through melting and iceberg calving [breaking off into the ocean]," he adds.

"What we have found is that despite small amounts of melting there is still rapid glacier retreat, so it seems that it doesn't take a lot to push the glacier out of balance."

The research has been published across two papers in Nature, here and here.