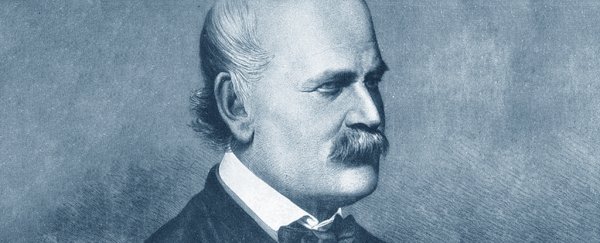

Ignaz Semmelweis was a 19th century Hungarian obstetrician who spent his life trying and failing to convince surgeons to wash their hands. Famous for testing and observing the spread of disease, Semmelweis is credited with uncovering the role of hygiene in the prevention of disease outbreaks.

At the time, however, his ideas were ridiculed. Ill health and deadly diseases was commonly believed to be caused by the corrosive effects of bad air, and not because of germs. Though his efforts to change the dominant medical culture of his day were ultimately in vain, Semmelweis is today regarded as a physician and scientist ahead of his time.

After briefly studying law at the University of Vienna, the young Semmelweis turned his interest to medicine and entered the profession with a major appointment at the Vienna General Hospital's First Obstetrical Clinic. He was tasked with observing patients, keeping records, attending to problematic deliveries, and - significantly - teaching students.

Next to the First Obstetrical Clinic was a 'second' ward staffed largely by midwives. Both clinics were for the underprivileged and poor, with admissions determined by availability and calendar. But enter the wrong one, and your chances of making it out again were dramatically reduced.

While the city's impoverished knew this all too well (the First clinic had a bad reputation on the streets), it took Semmelweis's astute record keeping for him to see the difference in mortality rates between the two clinics in cold, hard numbers.

In the hands of the doctor's ward, mothers had a one in 10 chance of suffering death at the hands of puerperal fever - a common condition back then, which is now known to be caused by an infection of Streptococcal bacteria. Attended to by midwives, however mothers barely had half that risk.

Stranger still, giving birth on the streets seemed almost safer by comparison. Semmelweis questioned, "What protected those who delivered outside the clinic from these destructive unknown endemic influences?"

How did hand-washing get started?

In 1847, while Semmelweis was absent from the clinic, his colleague and good friend Jakob Kolletschka passed away as a result of an infected wound suffered during a routine post mortem.

With Kolletschka's symptoms resembling those of the dying mothers, Semmelweis assumed there was a way for illness to move from cadavers to the patients. It would explain why patients risked death at the hands of the doctors, as opposed to midwives who had no dealings with the dead.

Such 'cadaverous particles', it was reasoned, could be removed by simply washing one's hands with clean, lightly chlorinated water.

Semmelweis used his authority in the clinic to set up a regime of handwashing among the medical students and other staff. The records showed a dramatic decline in patient mortality, from around 18 percent in April 1847 to less than 2 percent by July.

Unfortunately the practice was short lived. Semmelweis's position wasn't renewed, and in 1849 he returned home bitter and resentful over the stubbornness of his colleagues.

Why wasn't handwashing widely accepted?

Many of the more senior staff at the First Clinic were resistant to the idea of hand washing, with the grime and gore coating their hands a sign of their diligence and hard work. What's more, airing out the rooms once in a while should - in their opinion - be effective at reducing the disease-causing effects of foul air, or miasmas.

While Semmelweis presented medical records as evidence of his cadaverous particle hypothesis, and had many younger members of staff on his side, his somewhat acerbic attitude and reluctance to take the time to appeal to others in the profession weren't in his favour. Choosing to rely largely on the numbers as self-evident on their own, Semmelweis struggled to convince others of what he saw.

There was also the possibility that his Hungarian heritage - at a time of student uprising over civil rights that would lead to the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 - affected how his opinions were interpreted.

In time, Semmelweis would be vindicated. The likes of French chemist Louis Pasteur would help establish tiny microbes as causes of infection, while medical practitioners such as the famous British surgeon Joseph Lister would again popularise the merits of antisepsis and hygiene before the century's end.

Sadly, Semmelweis wouldn't live long enough to see it. He died in misery not 16 years after returning home, heart broken and hostile over his treatment, succumbing - with a touch of serendipity - to an infection, after being admitted to a mental institution.

Bio

Born: 1 July, 1818, to grocer József Semmelweis and Teréz Müller, daughter of a coachbuilder

Died: 13 August, 1865, from an infected hand wound

As a person: Semmelweis's last years back in Budapest were affected by bouts of depression and an obsession with the medical establishment's refusal to take his work seriously.

In 1865 he was lured to a newly opened mental institution, where he was admitted as a patient. His struggles with the wardens are thought to be responsible for a wound that turned septic, eventually claiming his life.

All Explainers are determined by fact checkers to be correct and relevant at the time of publishing. Text and images may be altered, removed, or added to as an editorial decision to keep information current.