A historic heat wave is bringing unprecedented temperatures to Western Europe, and is poised to expand northeastward to Scandinavia and into the Arctic by late this weekend.

Once above the Arctic Circle, the weather system responsible for this heat wave could accelerate the loss of sea ice, which is already running at a record low for this time of year.

First, residents of Paris, London, Brussels, Amsterdam, Munich, Zurich and other locations are suffering through dangerously high temperatures on Wednesday and Thursday.

Already on Wednesday, all-time national heat records in the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany had fallen, right on the heels of a late June heat wave that broke similar records in France and other countries.

The German meteorological agency noted that Wednesday's national record of 104.9 degrees Fahrenheit (40.5 Celsius) may last just a day before being broken on Thursday.

It's difficult to beat all-time heat records in mid-July, considering this is the hottest time of year. It's even more unusual to beat these records by a large margin, which is what is occurring now.

For example, Paris is likely to exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit (37.8 Celsius) on Wednesday by a few degrees, and break its all-time high temperature record of 104.7 degrees Fahrenheit (40.4 Celsius) by up to 3 degrees Fahrenheit on Thursday, with a forecast high of 108 Fahrenheit (42.2 Celsius).

The city's all-time high temperature record has stood since 1947.

Multiple all-time records were set elsewhere in France on Tuesday, both for daytime highs and hot nighttime low temperatures.

The UK Met Office is predicting that the country's all-time national heat record of 101.3 degrees Fahrenheit (38.5 Celsius) will be broken Thursday.

In addition, national heat records in Germany, where the mark to beat is 104.5 degrees Fahrenheit (40.3 degrees), could be set this week as well.

Heat of this intensity constitutes a significant public health threat, particularly for vulnerable populations like outdoor workers, the elderly, young children, those with compromised immune systems and anyone lacking the means to cool down.

In most of the cities currently affected, people lack air conditioning at home and in many public buildings and transit systems.

All-time record heat for the Netherlands- and should be warmer tomorrow! 🔥 https://t.co/GP2U4AljTF

— Eric Blake 🌀 (@EricBlake12) July 24, 2019

In London, where the record of 100.1 degrees Fahrenheit (37.8 Celsius) may be broken on Thursday, the subway system is not air conditioned throughout its network, leading some tube stations to see temperatures skyrocket well above 100 degrees Fahrenheit on platforms, and remain stifling aboard trains.

The average high in London for this time of year is 74 degrees Fahrenheit (23 Celsius).

An Omega block

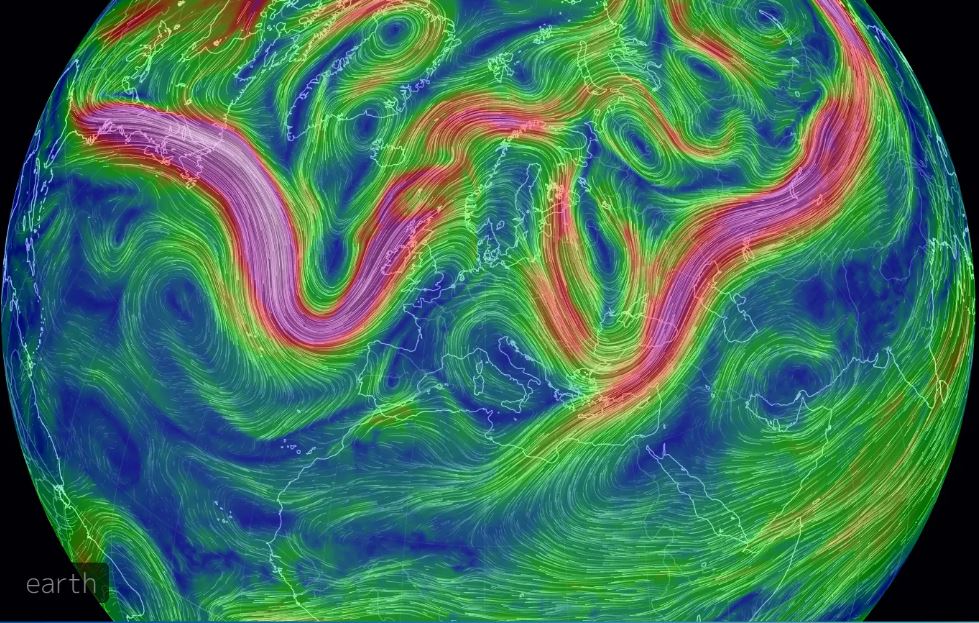

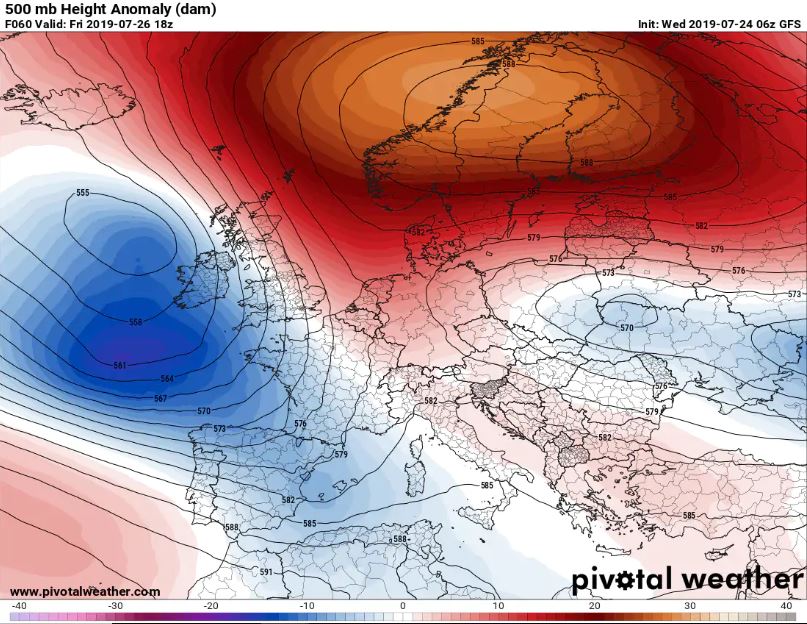

The heat is the result of a massive area of high pressure, also referred to as a heat dome, that is forcing the jet stream to divert around, it like a large detour in the sky. This is drawing hot air northward from the Sahara Desert, and keeping cooler maritime air at bay.

The upper air weather pattern formed by this resembles the shape of the Greek letter Omega, and meteorologists refer to it as an Omega block, since such features can be slow to dislodge.

Eventually, the high pressure area responsible for this heat wave is forecast to slide northeastward and park itself over Scandinavia and migrate north into the Arctic. As it does so, it could set records for the intensity of the high pressure area so far north at this time of year, and is likely to lead to heat records in Sweden, Norway, and Finland.

Right now, Arctic sea ice extent is at the lowest level on record for this time of year. Weather conditions during the Arctic melt season are a crucial factor in determining whether ice extent hits a record low in September or just misses it, as the past few seasons have done.

A heat dome over the Arctic, following unusually mild conditions throughout much of the Arctic Ocean during the melt season so far, could ensure a new and ominous record will be set this year.

Climate change is likely a key player in this

All weather is now occurring in an atmosphere that has been substantially altered by human activities, particularly the addition of large quantities of carbon dioxide, methane and other greenhouse gases from burning fossil fuels and land use change.

This has caused global average temperatures to increase by about 1.8 degrees since around the dawn of the industrial revolution, and in fact, 2019 is on its way to being one of the top 5 hottest years since instrument records began in the late 19th century.

Climate studies have consistently shown that heat waves are becoming more common, severe and longer-lasting as the global average surface temperature warms. In other words, heat waves are now hotter than they used to be, making it easier to set all-time records.

The Met Office, for example, reports that the UK is now experiencing "higher maximum temperatures and longer warm spells" than it used to.

"The hottest day of the year for the most recent decade (2008-2017) has increased by 0.8°C above the 1961-1990 average. Warm spells have also more than doubled in length - increasing from 5.3 days in 1961-90 to over 13 days in the most recent decade (2008-2017). South East England has seen some of the most significant changes, with warm spells increasing from around six days in length (during 1961-1990) to over 18 days per year on average during the most recent decade," the Met Office stated in a research report.

A different study published earlier this year found a record-breaking summer heat wave in Japan during 2018 "could not have happened without human-induced global warming".

And a recent rapid attribution analysis, which has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed science journal, showed that the early summer heat wave in Europe was made at least five times more likely to occur in the current climate than if human-caused warming had not occurred.

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.