After years of debate, the current geological epoch has finally been cut into three sections.

While some geologists clearly think it's a justified change, others feel the move was premature and deserved further discussion.

The International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) recently ratified the division of the Holocene into the Meghalayan, Northgrippian, and Greenlandian ages after siding with arguments that there were clear signs of a global change in the geological record.

The latest version of the International Chronostratigraphic Chart/Geologic Time Scale is now available! New #Holocene subdivisions: #Greenlandian (11,700 yr b2k)#Northgrippian (8326 yr b2k)#Meghalayan (4200 yr before 1950) https://t.co/IhvZHfHnWh#ChronostratigraphicChart208 pic.twitter.com/8Pf9Dnct7h

— IUGS (@theIUGS) July 13, 2018

This is the crux of the issue: scientists describe our planet's history according to important events affecting our planet's chemistry. Depending on which events are deemed the most impactful, the periods can be further broken down into smaller stages.

For example, a spike in iridium levels laid down in rock strata across the planet roughly 66 million years ago aligned with the end of the reign of the dinosaurs. This was enough to convince geologists to close the chapter on a period known as the Cretaceous and open a new one called the Paleogene.

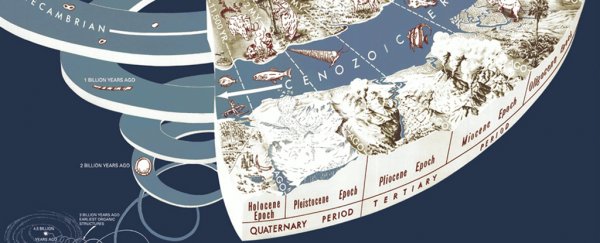

Right now we're in a period called the Quaternary, which is itself divided into two epochs – the Pleistocene and today's Holocene.

The Holocene stands out as a time of warming following the end of the last glaciation event just over 11,500 years ago, when the stage was set for agriculture and civilisation to develop.

Until now, our epoch has had no further subdivisions. Signs of a global drought that kicked off roughly 4,200 years ago have forced a rethink on whether that should continue to be the case.

Evidence has been collected from multiple sites all over the world, but the specific starting point of this most recent age is based on differences in oxygen isotopes in a stalagmite taken from a cave in northeast India.

"The isotopic shift reflects a 20 to 30 percent decrease in monsoon rainfall," geologist Mike Walker of the University of Wales explained to BBC News.

This deviation now defines a boundary between two new ages titled the Meghalayan and Northgrippian, a time when changes in monsoons forced civilisations to break apart and populations from Egypt to the Yangtze River Valley to migrate.

"The Meghalayan Age is unique among the many intervals of the Geologic Time Scale in that its beginning coincides with a global cultural event produced by a global climatic event," says Secretary General of the IUGS, Stanley Finney.

The start of the Northgrippian was set some 8,300 years ago, defined by the cold, fresh water from melting glaciers disrupting ocean currents.

While there's no argument that changes in the world's climate were of some significance, some argue whether they really are worthy of staking out new ages, prompting criticisms that the additions were too hasty.

"After the original paper and going through various committees, they've suddenly announced [the Meghalayan] and stuck it on the diagram," University College London geologist, Mark Maslin, told the BBC.

"It's official, we're in a new age; who knew?"

There is also an ongoing call to end the Holocene and officially recognise the start of an epoch of human-induced global change called the Anthropocene.

The changes don't rule out the addition of a whole new epoch, potentially marked by levels of radioactive material from above ground nuclear testing that peaked in 1965.

But they do demonstrate that science progresses just as much by debate on what members of a community find valuable as it does by empirical evidence itself. And that's okay.