To capture the first image of a black hole, researchers had to build a telescope as big as Earth by stitching together data from observatories around the globe. When the fuzzy, glowing image was finally released in 2019, every major newspaper ran it.

Now, that same supermassive monster – which sits at the center of a galaxy called Messier 87 – has surrendered more of its secrets. An analysis of 22 years' worth of observations taken of M87's core has confirmed its black hole spins.

"After the success of black hole imaging in this galaxy with the Event Horizon Telescope, whether this black hole is spinning or not has been a central concern among scientists," says astrophysicist and co-author Kazuhiro Hada from the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan.

"Now anticipation has turned into certainty. This monster black hole is indeed spinning."

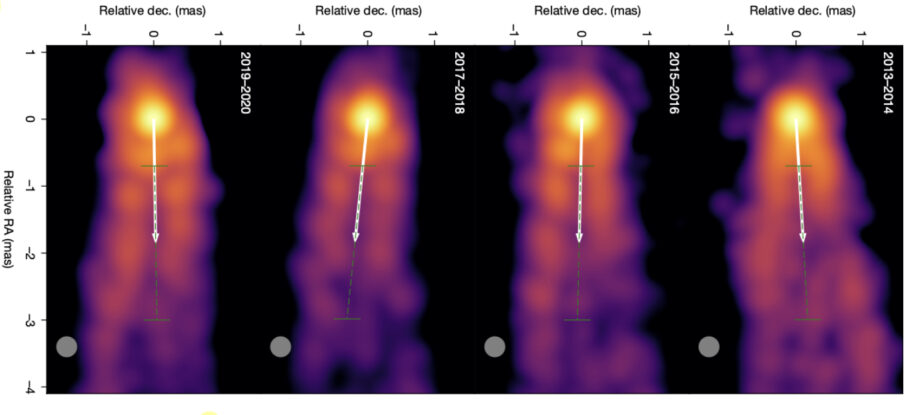

Using a global network of more than 20 telescopes, researchers analyzed 170 observations taken of M87 between 2000 and 2022.

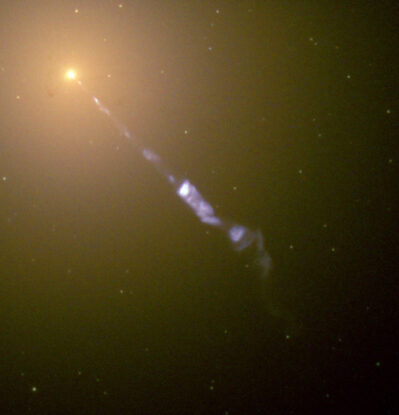

They could not observe anything inside the event horizon as the gravitational pull of black holes is so strong that they even make a prisoner of light. But they could track the black hole's magnificent jet, which spans 4,900 light years across and appears to travel almost five times faster than the speed of light due to an optical illusion known as superluminal motion.

This jet was first observed in 1918 by the astronomer Heber Curtis, but was famously captured by the Hubble Space Telescope.

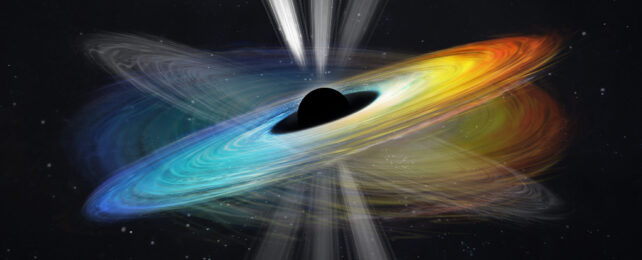

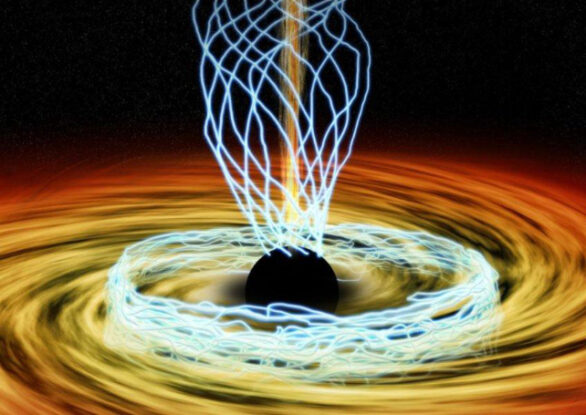

Scientists are not entirely sure how these powerful jets are created but it's thought that radiation and particles are funneled along the black hole's magnetic field lines.

The researchers found the black hole at the center of M87 was slowly changing the angle of its jet by around 10 degrees and then wobbling back to its original position. This cycle took about 11 years to complete.

From this variation in the tilt of the jet, the researchers could infer the presence of a spinning black hole.

Rotating black holes twist the space-time around them in a process called frame-dragging, which causes the accretion disk and the jet to topple sideways.

"Since the misalignment between the black hole and the disk is relatively small and the precession period is around 11 years, accumulating high-resolution data tracing M87's structure over two decades and thorough analysis are essential to obtain this achievement," says astrophysicist and co-author Cui Yuzhu.

M87 is of particular interest as it is only 54 million light-years away, which is much closer than other galaxies.

It has also fascinated star-gazers for centuries. M87 was first observed in 1781 by astronomer Charles Messier when he turned his telescope to a galaxy in the constellation Virgo. Messier 87 or M87, now bears his name.

Most black holes are thought to spin at almost the speed of light, and some black holes have already been shown to do this. A black hole that sits at the center of the NGC 1365 galaxy around 60 million light-years away was shown to rotate at 84 percent of the speed of light in 2013.

Using X-rays pulse patterns, scientists inferred that another black hole was spinning at 50 percent of the speed of light in 2019.

Why do black holes spin so fast? When matter collapses into a singularity or a black hole, it becomes extremely dense with very little volume.

But it retains its angular momentum. If the matter came from a spinning star, its rotational speed would increase upon compression, much like an ice-skater spins faster when they pull in their arms.

This paper was published in Nature.