The Moon is no longer pristine. We humans have been messing about up there for over half a century now, and our prints, dead equipment, crashed spacecraft, art, and even feces is speckled across its gray and cratered surface.

The time has now come, scientists say. Humans have become the dominant force acting on the geography of the Moon. And it's only going to get worse in the years ahead, as more and more missions head for Earth's fascinating satellite.

We need to put words to this, and actions to words, researchers say. They argue, in a new paper, that we need to declare a new epoch on the Moon – the Lunar Anthropocene – starting with the landing of Russia's Luna 2 spacecraft in 1959.

"The idea is much the same as the discussion of the Anthropocene on Earth — the exploration of how much humans have impacted our planet," says planetary geoarchaeologist Justin Holcomb of the Kansas Geological Survey at the University of Kansas.

"The consensus is on Earth the Anthropocene began at some point in the past, whether hundreds of thousands of years ago or in the 1950s. Similarly, on the moon, we argue the Lunar Anthropocene already has commenced, but we want to prevent massive damage or a delay of its recognition until we can measure a significant lunar halo caused by human activities, which would be too late."

Humans are brilliant at inserting themselves into, and thriving in, the diverse and strange environments the world has to offer. We've spread out and just made ourselves right at home wherever we happen to wander. It's definitely more comfortable for us in some places than others, but we find a way. And then we leave evidence of our existence everywhere we go.

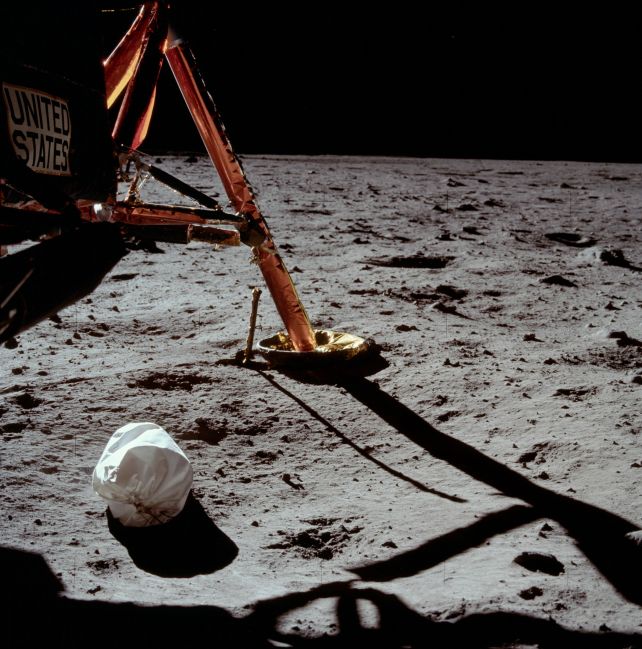

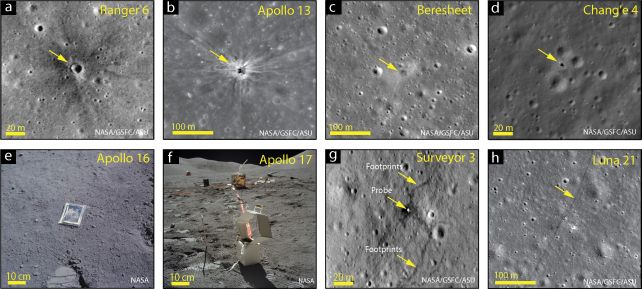

When we figured out how to get into space, we took our trash with us. The space around Earth is littered with our discarded junk. And when we send a spacecraft to the Moon, we leave some trace of our presence, a giant 'We were here' in the form of defunct equipment, garbage, or the crater and detritus left by a spacecraft impact.

In their paper, Holcomb and his colleagues, anthropologist Rolfe Mandel of the University of Kansas and geologist Karl Wegmann of North Carolina State University, have laid out their case for assessing and cataloging the impact of human activity on the Moon.

"Cultural processes are starting to outstrip the natural background of geological processes on the Moon," Holcomb says.

"These processes involve moving sediments, which we refer to as 'regolith,' on the Moon. Typically, these processes include meteoroid impacts and mass movement events, among others. However, when we consider the impact of rovers, landers and human movement, they significantly disturb the regolith. In the context of the new space race, the lunar landscape will be entirely different in 50 years."

Their goal is to refute the myth that the Moon is more-or-less unchanging. Human activity has created much more change than many of us realize, and we could damage the delicate lunar environment, including its reserves of water ice, and the tenuous exosphere that hangs over its surface.

In addition, we may want to look at preservation of our important lunar cultural history: the footprints, flags, photographs, and other important artifacts of the crewed lunar exploration that took place in the 1960s and 1970s.

This, they say, is our heritage, and an important part of human history as we took our first steps beyond our own world – yet only minimal effort is being made to track and preserve it.

"As archaeologists, we perceive footprints on the Moon as an extension of humanity's journey out of Africa, a pivotal milestone in our species' existence," Holcomb says.

"These imprints are intertwined with the overarching narrative of evolution. It's within this framework we seek to capture the interest of not only planetary scientists but also archaeologists and anthropologists who may not typically engage in discussions about planetary science."

The research has been published in Nature Geoscience.