The first map of Jupiter's magnetic field at a range of depths is in, and it solidifies something we already knew: that it's really, really, really weird. Aside from that, though, it's unlike anything else planetary scientists have ever seen.

We already knew that the gas giant's external magnetic field was an odd duck. For a start, it's incredibly strong. Jupiter's diameter is over 11 times that of Earth, but its magnetic field is a massive 20,000 times stronger.

It's also absolutely huge, and unrivalled in complexity - Earth's magnetic field is strong, but some of the structures seen in Jupiter's have no terrestrial counterpart. It's thought that this complexity may have something to do with Jupiter's rapid rotation and large liquid metallic hydrogen interior.

But now Juno, orbiting Jupiter's poles, is allowing unprecedented access to the dynamics of this strange magnetic field, taking much closer observations than have ever been possible.

Scientists from the US and Denmark have used data from eight Juno orbits to map the magnetic field in unprecedented detail at depths of 10,000 kilometres (6,214 miles), and found that it's much stranger than they were expecting.

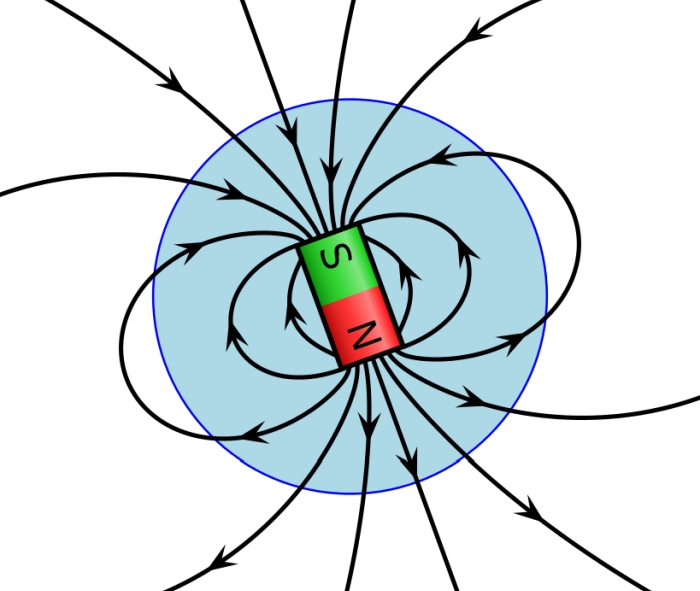

Earth's magnetic field is predominantly dipolar, as if it had a bar magnet running through the centre of the planet, with the poles of the magnet at the planet's poles, emerging from the South pole and re-entering at the North. There are also non-dipolar components, evenly spread out throughout the hemispheres.

If you could see it, it would look a little something like this.

(Geek3/Wikimedia Commons)

(Geek3/Wikimedia Commons)

But that's not how Jupiter's turned out.

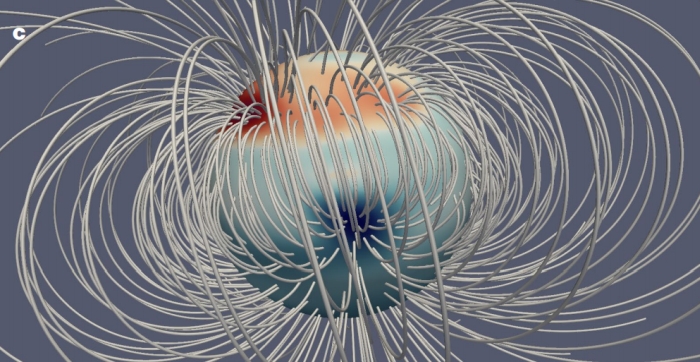

Instead, the field emerges from a broad section of the northern hemisphere, re-entering around the south pole - and a highly concentrated region just south of the equator, what the researchers are calling the Great Blue Spot. Elsewhere, the field is much weaker.

Take a look for yourself:

(Moore et al./Nature)"Before the Juno mission, our best maps of Jupiter's field resembled Earth's field," planetary scientist Kimberly Moore of Harvard University told Newsweek.

(Moore et al./Nature)"Before the Juno mission, our best maps of Jupiter's field resembled Earth's field," planetary scientist Kimberly Moore of Harvard University told Newsweek.

"The main surprise was that Jupiter's field is so simple in one hemisphere and so complicated in the other. None of the existing models predicted a field like that."

In another strange discovery, the researchers found that the non-dipolar part of the magnetic field is almost entirely concentrated in the northern hemisphere. The whole thing is deeply lopsided and utterly unique.

This indicates that something unknown is occurring in Jupiter's interior.

Magnetic fields are generated by conductive liquids inside a planet. When combined with the planet's rotation, they generate magnetism. This is called a planetary dynamo. In Earth, the dynamo operates within a thick, uniform shell.

The researchers believe their finding indicates that Jupiter's does not. One model, they proposed, is that Jupiter's core is not a solid, tiny ball of ice and rock, but a slush of rock and ice fragments partially dissolved in the liquid metallic hydrogen.

This could create layers, the dynamics of which generate an asymmetrical magnetic field.

Another explanation could be helium rain, which could destabilise the field, although, the researchers noted, this would be unlikely to account for the hemispheric asymmetry.

In total, Juno is planned to make 34 orbits of Jupiter. The team is planning to use future observations to try and solve the mystery.

Their research has been published in the journal Nature.