Astronomers have just found a cosmic cannonball.

Around a star some 730 light-years away orbits an exoplanet the size of Jupiter, but with a density that boggles the mind. Astronomers have determined that the world, named TOI-4603b, has a mass of nearly 13 Jupiters.

That means it's nearly 3 times the density of Earth, and just over 9 times the density of Jupiter. And it's really cuddly with its star, with a tight orbit of just 7.25 days.

This places it in a small but significant category of worlds that defy our understanding of planetary formation and evolution. This discovery, accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics Letters, is available on preprint server arXiv.

"It is one of the most massive and densest transiting giant planets known to date," write a team of astronomers led by Akanksha Khandelwal of the Physical Research Laboratory in India, "and a valuable addition to the population of less than five massive close-in giant planets in the high-mass planet and low-mass brown dwarf overlapping region that is further required for understanding the processes responsible for their formation."

Theoretically, there's a limit to how much mass a planet can have. That's because, above a certain critical limit, the temperature and pressure placed on the core is sufficient to ignite nuclear fusion, the process of smushing together atoms to create heavier elements.

For a star, the minimum mass at which this process starts is around 85 Jupiters; at that point, hydrogen atoms start fusing into helium.

The upper mass limit for a planet is thought to be around 10 to 13 Jupiters. And the objects that straddle the gap between them are known as brown dwarfs. These don't have enough mass for hydrogen fusion; however, their cores can fuse deuterium, a heavy isotope of hydrogen that doesn't quite need as much heat and pressure.

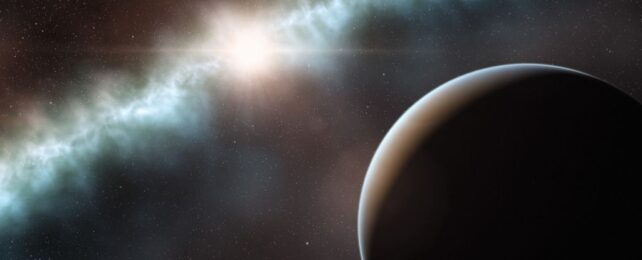

Stars form from the top down, when a dense clump in a molecular cloud collapses under gravity to form a protostar. The star then grows by slurping up material from the cloud around it, which arranges into a disk.

The dust and gas left over after this process forms planets, which start from the bottom up as bits of rubble start to stick together, eventually forming clumps that grow into planets.

Brown dwarfs are thought to form like stars, from a clump of molecular cloud that collapses under gravity. They're usually found orbiting stars at quite a wide separation, at a minimum of a five astronomical units (AU) – that's five times the distance between Earth and the Sun.

Astronomers believe that they form in a similar way to stars, collapsing from a clump of material in a cloud, and there's a remarkable "desert" of brown dwarfs with close orbits.

TOI-4603b was first spotted in data from NASA's exoplanet-hunting space telescope TESS, which studies patches of the sky looking for faint, regular dips in starlight that suggest the presence of an orbiting exoplanet. The TESS data suggested a world 1.042 times the radius of Jupiter, whipping around its star in just over a week.

The team followed up seeking radial velocity measurements. That's the amount by which an exoplanet's gravity moves its host star, as the two bodies orbit a mutual center of gravity. If you know the mass of the star, you can work out the mass of the exoplanet by calculating how much the star is moving around.

This is how the researchers derived a mass for TOI-4603b of 12.89 times the mass of Jupiter. Combining that with the object's radius allowed the team to arrive at an average density of 14.1 grams per cubic centimeter. Earth's density, for context, is 5.51 grams per cubic centimeter. Jupiter's is 1.33 grams per cubic centimeter. Lead has a density of 11.3 grams per cubic centimeter.

That's not at all strange, for a brown dwarf, which on average is around 0.83 times the radius of Jupiter; one brown dwarf, with a radius 0.87 times that of Jupiter, has a mass of around 61.6 Jupiters, for example. These things can get much denser than TOI-4603b.

TOI-4603b fits most of the criteria to be classified as an exoplanet, and that's what Khandelwal and her colleagues have called it. But it's right on the cusp of the brown dwarf mass limit, which means that it could be an important world for understanding how brown dwarfs and giant planets form, and how their relationship to their stars evolve.

For example, the exoplanet has an orbit that is significantly oval, or eccentric, suggesting that it is still settling into it. And the star also has a brown dwarf companion, orbiting at around 1.8 astronomical units, which could have gravitationally interacted with TOI-4603b. These clues suggest that the exoplanet is migrating closer to the star from a more distant position.

A similar object is a world called HATS-70b, which at 12.9 times the mass of Jupiter and 1.384 times its radius, is less dense than TOI-4603b, but similarly close to its star, and also shows signs of migration.

"Detection of such systems," the researchers write, "will offer us to gain valuable insights into the governing mechanisms of massive planets and improve our understanding of their dominant formation and migration mechanisms."

The research has been accepted in Astronomy & Astrophysics Letters, and is available on arXiv.