The two largest planets in the Solar System – Jupiter and Saturn – have a lot in common. They're made of very similar stuff, they spin at similar speeds, and radiate internal heat similarly. Heck, they even both hoard moons in a similar way.

However, there's a difference between the planets that has long puzzled scientists: the giant, vortical storms that cap their poles.

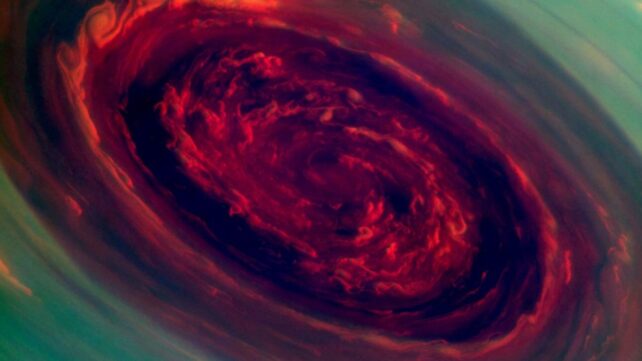

Saturn has one huge storm on each pole.

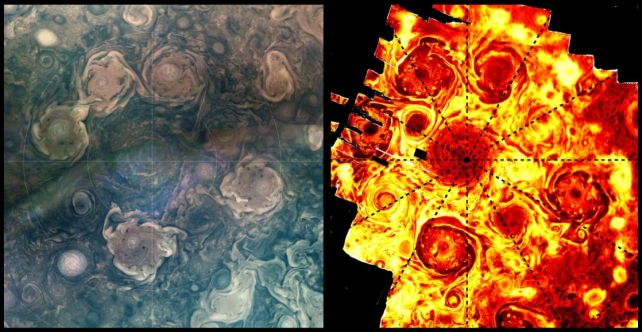

Jupiter's poles are each dominated by a single large storm surrounded by a diadem of smaller ones.

Related: We Might Finally Know How Jupiter's Weird Polar Storms Stay Together

Now, a pair of planetary scientists thinks that they may have solved the mystery. It's down to how the storms form and connect into the planetary interior: whether the atmosphere allows free growth, as Saturn's atmosphere does, or whether it effectively imposes storm size limits, like Jupiter's.

In the team's model, this comes down to how strongly storms are coupled to deeper layers.

"Our study shows that, depending on the interior properties and the softness of the bottom of the vortex, this will influence the kind of fluid pattern you observe at the surface," says planetary scientist Wanying Kang of MIT.

"I don't think anyone's made this connection between the surface fluid pattern and the interior properties of these planets. One possible scenario could be that Saturn has a harder bottom than Jupiter."

The weather on Jupiter and Saturn is legendary. Dominated by a puffy, gaseous atmosphere, each planet is roiled by turbulent storms, powerful bands of wind, and thick clouds that swirl into patterns resembling abstract expressionism.

Both planets have been the subject of dedicated spacecraft observation campaigns – Cassini for Saturn and Juno for Jupiter. These groundbreaking probes revealed that, for all their similarities, the two planets have their own idiosyncratic polar storm configurations.

"People have spent a lot of time deciphering the differences between Jupiter and Saturn," says atmospheric scientist Jiaru Shi of MIT. "The planets are about the same size and are both made mostly of hydrogen and helium. It's unclear why their polar vortices are so different."

To find out, the two scientists developed a two-dimensional model of surface fluid dynamics to replicate the surface vortices seen on both planets.

"In a fast-rotating system, fluid motion tends to be uniform along the rotating axis," Kang says. "So, we were motivated by this idea that we can reduce a 3D dynamical problem to a 2D problem because the fluid pattern does not change in 3D. This makes the problem hundreds of times faster and cheaper to simulate and study."

On gas giant planets, giant storms are born of smaller motional building blocks, such as convection, which grow larger and larger. However, their ultimate size is determined by various limits, including the depth of the atmosphere's layering, the force with which the atmosphere is being stirred (a phenomenon called 'forcing'), and the rate at which friction is dissipated.

Shi and Kang found that the order in which those limits are reached makes a huge difference in the vortical patterns that emerge on the visible surface of the atmosphere.

Jupiter's atmosphere is deep and energetic enough for multiple vortices to form, but early turbulence prevents them from mooshing together into one big vortex, so they manifest as a surprisingly geometric pepperoni pizza of polar storms.

In other words, according to the model, Jupiter's layering is weaker, its forcing is stronger as it radiates heat from its center, and energy isn't drained as quickly through friction. Combined, this means the discrete storm structure remains intact at the surface.

By contrast, Saturn's atmosphere is layered more deeply. There, either weaker forcing reduces deep turbulence, or more energy is lost to friction, or a combination of both, removes the barrier preventing its vortices from merging, so all the storms crash together into one giant one.

And this could all be affected by the density of the bottom layer at which the vortex forms. It's not exactly hard proof, but the team's findings suggest that the patterns of the polar storms on each of the planets could be inscribing clues about the environment in which they formed.

Related: The Moment We've Been Waiting For: JWST Zooms Into The 'Eye of Sauron'

"What we see from the surface, the fluid pattern on Jupiter and Saturn, may tell us something about the interior, like how soft the bottom is," Shi says.

"And that is important because maybe beneath Saturn's surface, the interior is more metal-enriched and has more condensable material, which allows it to provide stronger stratification than Jupiter. This would add to our understanding of these gas giants."

The research has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.