Scientists have discovered a unique protein that gives away the presence of inactive HIV in the body.

Sniffing out these hidden caches of the virus is something researchers have been trying to do for decades. Now that we have a lead, the finding could speed up research on a cure.

Thanks to modern antiretroviral therapies, for many people, HIV is not the death sentence it once was. But we still don't have a reliable way of permanently flushing it out of someone's system.

Drugs can keep the virus in check, but unfortunately HIV has a major weapon - it stows away in secret reservoirs in the immune system. There it lies dormant until conditions are more suitable to re-emerge.

That's why people infected with HIV have to spend a lifetime on expensive drugs, because the virus can take only weeks to come back from its latent state if drug treatment is stopped.

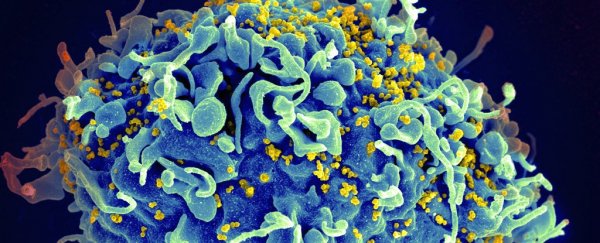

Those nasty secret reservoirs HIV creates are located in long-lived immune cells known as resting T cells. Because the virus hijacks these cells and integrates its genetic material into the DNA of the patient, it makes reservoir T cells extremely hard to track down.

Now a team of French scientists has managed to achieve this important milestone in HIV research by discovering a biomarker that exists only on the surface of T cells that harbour the latent virus.

"Since 1996, the dream has been to kill these nasty cells in hiding, but we had no way to do it because we had no way to recognise them," says virologist Monsef Benkirane from University of Montpellier in France.

Benkirane's team discovered that a specific protein, called CD32a, hangs out on the surface of T cells with a latent HIV infection, but is not found on uninfected T cells, or even T cells with active HIV.

This is huge. Having CD32a as a biomarker for HIV reservoirs means scientists have a better chance to track them down in a patient's blood. This paves the way for more research into the mechanisms that allow HIV to create such reservoirs in the first place.

Armed with such knowledge, scientists could then find ways to actually get rid of these HIV nests for good.

The team first detected the protein in a lab-made model of HIV infection, before moving on to test it as a biomarker in actual blood samples from 12 people who live with HIV and are receiving treatment.

They separated T cells with CD32a from other T cells in the blood samples, and found that the cells with this particular protein indeed had latent HIV harboured inside them.

Unfortunately, it's not a smoking gun in every case, since the protein was found only on about half of all latently infected T cells.

Douglas Richman from University of California San Diego, who wasn't involved in the research, writes that "the eradication of latent HIV would require a much greater reduction in the number of latently infected cells in the body."

But it's an extremely encouraging first step in the long search for a marker that could help us track down the nasty virus once it goes into hiding.

Tony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Disease, told Nature that a good next step would be to replicate the findings in more blood samples from a larger variety of patients who have the virus.

It's still way too soon to say that we're on the path to an actual HIV cure, but the news is super-exciting to researchers who have been hammering away at this problem for decades.

"I really hope this is correct," says Fauci. "The fact that this work has been done by such competent investigators, and the data looks good, makes me optimistic."

In a world where HIV continues to be a major health issue, this discovery indeed gives cause for optimism.

About 36.7 million people around the world live with HIV, but only 17 million have access to antiretroviral therapy, according to data from the US CDC.

The scientists have already filed a patent for the diagnostic and therapeutic use of the new biomarker.

This research has been published in Nature.