The way we sleep can reveal a great deal about our overall health. But while many of us focus on the hours of shut-eye we get, new research suggests we should pay more attention to the timing and consistency of our bedtime.

Researchers have now found that those with the poorest sleep rhythms may face a 2.8-times-higher risk of Parkinson's disease, and a 1.6-times-higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes, compared to those with consistent patterns of wakefulness and sleep.

The findings come from the sleep data of more than 88,000 people in the UK Biobank, and while the results can only reveal correlations, they could point future clinical research in new directions.

Altogether, scientists at Peking University and the Army Medical University in China considered the health effects of six sleep traits: length, onset, rhythm, extent and efficiency of sleep, and frequency of wake-ups during the night.

Related: A Study Found Too Much Sleep Increases Risk of Death. Here's Why.

During the average 6.8-year follow-up, 172 diseases were associated with these sleep characteristics, with many tied to just one trait.

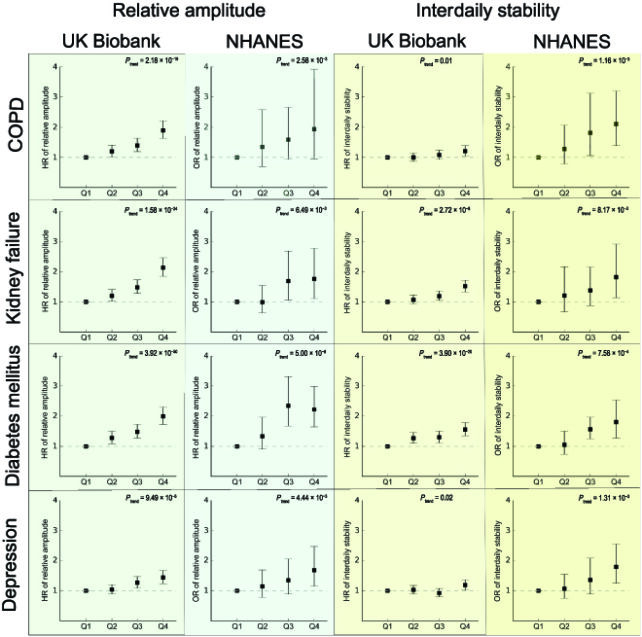

To make the findings more robust, the associations were successfully replicated using another large database: the United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Across both analyses, sleep duration (as measured by wearable sensors) showed a relatively weak association with disease risk, despite the fact that in surveys, many participants expressed greater concern over how much they slept, rather than how they slept.

Sleep rhythm, meanwhile, showed three times as many disease links as those associated with sleep duration and onset. In fact, it was associated with nearly half of the study's 172 diseases.

The term 'sleep rhythm' essentially refers to cycles of wakefulness and sleep, from when a person goes to bed, to when they wake each and every day.

A more robust and regular sleep rhythm seems to be tied to healthier outcomes.

Senior author and epidemiologist Shengfeng Wang from Peking University argues it is "time we broaden our definition of good sleep beyond just duration."

"The existing literature has disproportionately focused on sleep duration rather than other sleep traits," write the study authors, led by Yimeng Wang from China's Army Medical University.

In the current study, the most erratic sleep rhythms, as opposed to the most consistent ones, were linked to type 2 diabetes, primary hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, acute kidney failure, and depression – to name just a few.

One of the strongest associations was with Parkinson's disease, which previous studies have also linked to sleep disorders.

Sleep onset and sleep quality were also associated with several diseases.

Those who went to bed after 12.30 am, for instance, were 2.6 times more likely to develop liver cirrhosis compared to those who went to bed before 11.30 pm.

In addition, the least efficient sleepers showed a nearly 1.8-fold increase in respiratory failure compared to those who slept the most efficiently.

The data is based on wearable sleep monitors as well as subjective reports, and that seems to be an important combination.

Nearly a quarter of self-reported 'long sleepers' actually slept fewer than 6 hours a night. The findings indicate that purely relying on surveys, as previous sleep studies have done, may not be reliable.

"For example, some participants with difficulty falling asleep or keeping stable sleep may have spent a long time in bed but have short real sleep," the researchers explain.

"As evidenced by our analyses, this dramatic misclassification of sleep duration has introduced substantial bias to the estimation of effect size for a number of diseases, including stroke, ischemic heart diseases, cardiovascular disease, and depressive episode and recurrent depressive disorder."

"Our findings underscore the overlooked importance of sleep regularity," concludes Wang.

The study was published in Health Data Science.