Despite careful preservation efforts, researchers have discovered at least 16 different types of microplastics infiltrating a 2nd-century archeological site in York, UK, up to 7 meters (23 feet) deep.

This region is known for its Viking and Roman history.

"The presence of microplastics can and will change the chemistry of the soil, potentially introducing elements which will cause the organic remains to decay," explains archaeologist David Jennings from York Archaeology. "If that is the case, preserving archaeology in situ may no longer be appropriate."

This is a massive concern for archeology as protecting discoveries in their original location has been a global standard for generations.

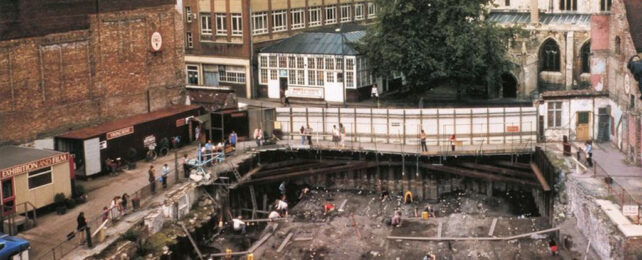

The pilot study tested samples collected from Wellington Row digs in 1988 and 1989 and compared them to freshly retrieved soil from equivalent depths in nearby locations.

To the dismay of University of Hull ecotoxicologist Jeanette Rotchell and colleagues, both groups of samples contained plastic fragments, between 1 μm and 5 mm in size.

And they did not match the plastics associated with the sample's storage.

So these insidious petrochemical waste products had infiltrated deep into the soil, even as far back as the 1980s, continuing the ongoing trend of finding plastic microparticles in every environment tested on Earth, from the highest peaks, to the deepest ocean trenches and the insides of our organs.

"We think of microplastics as a very modern phenomenon, as we have only really been hearing about them for the last 20 years, when Professor Richard Thompson revealed in 2004 that they have been prevalent in our seas since the 1960s with the post-war boom in plastic production," says Jennings.

"This new study shows that the particles have infiltrated archaeological deposits, and like the oceans, this is likely to have been happening for a similar period, with particles found in soil samples taken and archived in 1988 at Wellington Row in York."

The most common plastics identified were ethylene vinyl alcohol/ethylene-vinyl acetate which is used for its flexibility in packaging, and PP:PE copolymer, used for its durability in carpets and molding of car bumpers.

The researchers suspect the nearby River Ouse, rainfall, and leaking water mains contribute to these deep-ground microplastic deposits. Tests in a nearby well that receives water from the river overflow contained similar chemical profiles.

Ironically, the team points out, microplastic 'techno fossils' could provide very fine dating resolution for future archeologists, given the ratios and types of plastic polymers shift so markedly over time.

"We are familiar with plastics in the oceans and in rivers. But here we see our historic heritage incorporating toxic elements," explains University of York archeologist John Schofield.

"To what extent this contamination compromises the evidential value of these deposits, and their national importance is what we'll try to find out next."

This research was published in Science of the Total Environment.