Scientists investigating the possible health effects of microplastics have uncovered some disturbing initial results in an experiment based on mice.

When old and young rodents drank microscopic fragments of plastic suspended in their water over the course of three weeks, researchers at the University of Rhode Island found traces of the pollutants had accumulated in every organ of the tiny mammal's body, including the brain.

The presence of these microplastics was also accompanied by behavioral changes akin to dementia in humans, as well as changes to immune markers in the liver and brain.

"To us, this was striking. These were not high doses of microplastics, but in only a short period of time, we saw these changes," explains neuroscientist Jaime Ross.

"Nobody really understands the life cycle of these microplastics in the body, so part of what we want to address is the question of what happens as you get older. Are you more susceptible to systemic inflammation from these microplastics as you age? Can your body get rid of them as easily? Do your cells respond differently to these toxins?"

The results may not translate directly to humans, but studies involving animal models like these are a key first step in clinical research.

Recently, scientists have found microplastics hiding in the human intestine, circulating in our bloodstream, gathering deep in the lungs, and seeping through to the placenta.

In 2021, toxicologists warned that future studies urgently need to address what these pollutants are doing to our health, especially since exposure is now all but impossible to avoid.

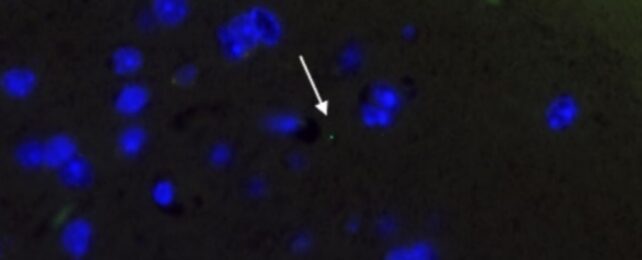

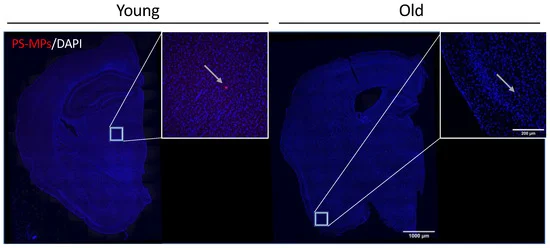

In the recent experiments, both old and young mice were given water that was treated with microplastics made of fluorescent polystyrene.

Some of the mice were also given normal drinking water as a control.

During the three-week trial, the mice had their behavior regularly assessed during open field tests that encourage exploratory behavior. They also undertook light-dark preference tests, which are based on a rodent's natural aversion to brightly lit areas.

Compared to the control group, mice who drank microplastic-contaminated water for three weeks showed significant behavioral changes, changes that were especially pronounced among older mice.

At the conclusion of the three weeks, red fluorescent particles of microplastics were found in every type of tissue the team examined: the brain, liver, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, heart, spleen, and lungs. The plastics were also in the poop and urine of the mice.

The fact that the pollutants were detected outside the digestive system suggests they are undergoing systemic circulation.

Their presence in the brain is especially concerning. It indicates that these potentially toxic pollutants can cross the immune barrier that separates the central nervous system from the rest of the body's bloodstream, possibly leading to neurocognitive issues.

The findings join another study from earlier this year that found microplastics in the brains of mice just two hours after eating a contaminated meal.

In 2022, a similar study also found that ingested polystyrene microplastics can accumulate in the brains of mice, triggering inflammation and impairing their memory. This study did not, however, identify any behavioral changes among mice during an open field test.

Despite the discrepancies between results, Ross and her colleagues argue it is now evident polystyrene microplastics can travel to the mammal brain and exert detrimental effects after absorption.

In their recent study, they found a protein called GFAP, which supports cells in the brain, had decreased in abundance following the ingestion of microplastics.

"A decrease in GFAP has been associated with early stages of some neurodegenerative diseases, including mouse models of Alzheimer's disease, as well as depression," says Ross.

"We were very surprised to see that the microplastics could induce altered GFAP signaling."

Ross plans to investigate these concerning changes in future research.

The study was published in the International Journal of Molecular Science.