We've known for a long time that women are more likely than men to have migraine attacks.

As children, girls and boys experience migraine equally. But after puberty, women are two to three times more likely to experience this potentially debilitating condition.

Recently, an Australian study showed it may be even more common than we previously thought – as many as one in three women live with migraine.

Related: Here's Why Weather Can Trigger Your Migraines, And How to Ease The Pain

For comparison, migraine affects roughly one in 15 men in Australia.

So, what's behind the difference? Here's what we know.

More than a headache

Migraine is not just a bad headache – it is a complex disorder that causes the brain to process sensory information abnormally.

This means "migraine brains" can have difficulty processing information from any of the five senses:

- sight (leading to problems with light sensitivity and glare)

- sound (leading to noise sensitivity)

- smell (certain smells can trigger headaches)

- touch (leading to face or scalp tenderness)

- taste (causing distorted taste, nausea and vomiting).

Migraine attacks typically last anywhere from four hours to three days – but can be longer.

In addition to the symptoms above, attacks can include throbbing head pain, dizziness, fatigue and difficulty concentrating. It is these extra symptoms that help diagnose migraine – not the location of head pain or pain severity.

Why are attacks more frequent in women?

Puberty is when the difference between men and women emerges. This is when our bodies massively increase the production of sex hormones.

People are often surprised to learn that both men and women produce oestrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. Testosterone levels are higher in men, whereas women have higher levels of oestrogen and progesterone.

However, it is not just the type of hormone that makes a difference, but the way they fluctuate over time.

For many women, there are certain "milestone moments" when their migraine tends to worsen due to hormonal fluctuations – puberty, menstruation, pregnancy and perimenopause (the lead-up to your final period).

For example, some women notice migraine flare-ups every month, linked to phases in their monthly menstrual cycle when oestrogen levels drop.

They might even be able to predict when their period will start, as migraine attacks typically start a few days before the bleeding.

How hormones affect the brain

Women with migraine can be more sensitive to hormonal changes. This is particularly the case for sudden decreases in oestrogen. But even more subtle changes to hormone levels can cause migraine attacks.

These hormonal changes can activate brain processes that trigger migraine, such as cortical spreading depression. This is a very slow wave of electrical activity that spreads in the brain, causing some areas to function more slowly than others after it passes.

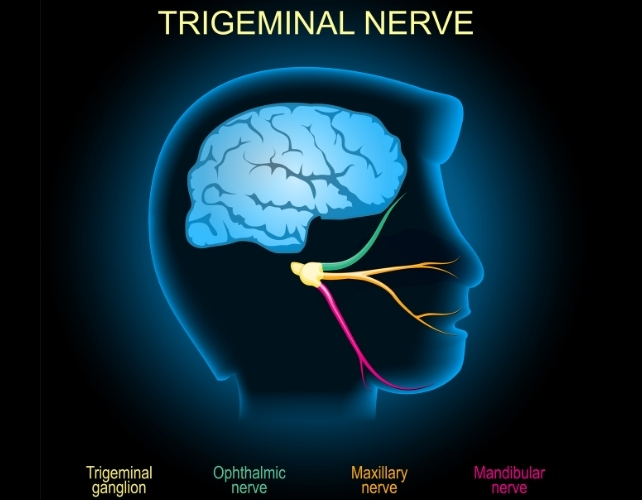

Decrease in oestrogen can also affect how we receive and process information through the trigeminal nerve. This plays a key role in the onset and maintenance of migraine pain.

All kinds of fluctuations can be a trigger

Pregnancy can often destabilise migraine again and make attacks more likely, even when someone has previously enjoyed a period of good migraine control.

Migraine symptoms often become uncontrolled in the first trimester in particular, due to rapid hormonal changes needed to sustain a pregnancy. This usually settles in the second and third trimesters, when hormonal changes stabilise.

Related: Hormone Discovery Could Explain Why Migraines Are Worse When Menstruating

However, giving birth is yet another change.

Towards the end of pregnancy, oestrogen levels can be 30 times higher than pre-pregnancy levels, and progesterone can be 20 times higher. When these hormones plummet back to normal after giving birth, migraine attacks can often sharply worsen again.

Perimenopause can also involve random surges of oestrogen from the dwindling supplies of eggs within the ovaries – which previously produced these hormones cyclically and in abundance. This irregular hormone production can cause random spikes in migraine attacks. It can be extra challenging when combined with other symptoms of menopause, such as hot flushes or mood changes.

Hormonal contraceptives and menopause hormone therapy can also affect migraine control. Sometimes, supplementing hormones at a regular, steady daily dose can help manage the hormone-sensitive headaches and other symptoms. However, for others, adding extra hormones can cause head pain to flare up.

Does migraine run in the family?

Genes also play a role. It's not a coincidence that migraine is passed down in families through the maternal side.

This is because mothers pass on mitochondria to children (while fathers do not). Mitochondria are parts inside the cell that control energy.

People with migraine have fewer functional enzymes within their mitochondria, meaning their brains are in an energy-deficient state. This worsens with migraine attacks as there is even more stress on the system.

This is also why extra stress (such as sleep deprivation, missed meals, or emotional stress) can trigger a migraine and worsen pain.

There is also a strong link between migraine in women and anxiety and depression – conditions women are more likely to develop in response to stressful life events.

Knowing your own patterns

If you suspect hormones may be affecting your migraine attacks, it is helpful to keep a diary of symptoms, including headaches. Mark each day per month where you get migraine symptoms, as well as your period, to find patterns.

Identifying patterns in pain flares helps doctors guide you to a personalised medication plan, which may include hormone therapies or non-hormonal therapies.![]()

Lakshini Gunasekera, PhD Candidate in Neurology, Monash University; Caroline Gurvich, Associate Professor and Clinical Neuropsychologist, Monash University; Eveline Mu, Research Fellow in Women's Mental Health, Monash University, and Jayashri Kulkarni, Professor of Psychiatry, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.