An investigation by researchers from Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in the US has filled in a missing link between the toxic build-up of proteins in the neurodegenerative condition Parkinson's disease and the death of critical brain cells.

The result of three years of research, the discovery connects alpha-synuclein proteins to a breakdown in mitochondrial function, both previously linked to Parkinson's.

"We've uncovered a harmful interaction between proteins that damages the brain's cellular powerhouses, called mitochondria," says neuroscientist Xin Qi.

"More importantly, we've developed a targeted approach that can block this interaction and restore healthy brain cell function."

Related: 'Zap-And-Freeze' Brain Imaging Could Reveal The Secrets of Parkinson's

Research has previously shown that toxic, abnormal clumps of alpha-synuclein damage neurons in Parkinson's. We also know that the disease is associated with weaker mitochondria, depriving neurons of the energy they need to work effectively.

Those two malfunctions have been linked before, but this new study provides a clearer idea of how.

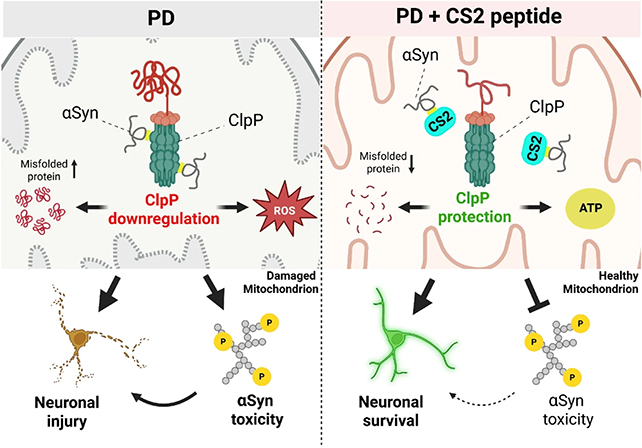

In lab tests, the team observed interactions between alpha-synuclein and an enzyme called ClpP, which helps manage mitochondrial waste removal.

Their results suggest it is the way that alpha-synuclein binds to ClpP that disrupts mitochondria function, producing the knock-on effects so common in Parkinson's – including a decline in dopamine production.

The most significant part of the research was the development of a potential treatment to counter this damaging biochemical reaction. A short length of protein called CS2 was designed to act as a decoy for alpha-synuclein, diverting its attention away from ClpP and cell mitochondria.

In tests on human brain tissue, mouse models, and neurons developed in the lab, CS2 was shown to have positive effects. It reduced brain inflammation and restored some motor and cognitive function in animals.

"This represents a fundamentally new approach to treating Parkinson's disease," says neurophysiologist Di Hu. "Instead of just treating the symptoms, we're targeting one of the root causes of the disease itself."

Researchers estimate it might be five years until human clinical trials could evaluate CS2's safety and efficiency in humans – this kind of biological tweaking can have unintended consequences that scientists will need to extensively test for.

Nevertheless, it's a promising step forward for Parkinson's research. Not only does the study identify one of the faults that is associated with the disease at the smallest molecular level, it also demonstrates a way it can potentially be repaired.

All of this is in the context of what is already known about Parkinson's. It's a hugely complex disease where causes are difficult to differentiate from consequences – it's likely that multiple treatment approaches are going to be needed to finally find ways to cure the disease and stop it from developing in the first place.

"One day we hope to develop mitochondria-targeted therapies that will enable people to regain normal function and quality of life, transforming Parkinson's from a crippling, progressive condition into a manageable or resolved one," says Qi.

The research has been published in Molecular Neurodegeneration.