Researchers have come up with a clever new way of freezing brain cells just as they fire out a signal, meaning processes that normally happen too quickly to observe can be studied in detail – and perhaps offer clues for treating conditions like Parkinson's disease, where this signaling becomes disrupted.

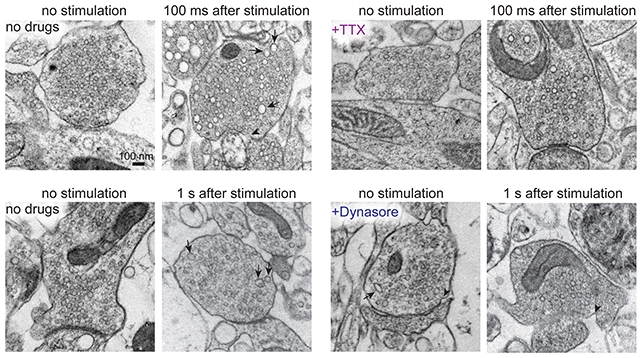

The process, called 'zap-and-freeze', involves jolting brain cells with electricity and then freezing them within milliseconds, under high pressure. Here, researchers led by a team from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in the US tested the technique on brain tissue from both mice and humans.

These tests revealed details of the workings of synapses that handle neuron-to-neuron communication, and of the vesicles that hold the chemical messages to be delivered. These interactions are fundamental for everything from memory to learning.

Related: 'Brainquake' Discovery Could Change What We Know About Schizophrenia

"This approach has the potential to reveal dynamic, high-resolution information about synaptic membrane trafficking in intact human brain slices," write Johns Hopkins neuroscientist Chelsy Eddings and colleagues in their published paper.

In particular, the researchers observed endocytosis in action, a recycling process that removes used vesicles and creates new ones, ready to send more messages to neurons.

The researchers found evidence of ultrafast endocytosis – happening in less than 100 milliseconds – in both mouse and human brain slices, preserved in such a way that cells retain most of their normal structure and function.

The team also identified a protein called dynamin1xA as being essential to this endocytosis process.

By discovering these details for the first time, in brain tissue donated by people who had brain lesions removed, scientists now have a better understanding of the mechanisms that go awry in brain disease.

What's more, it's encouraging that the results match up so closely between animals and people: The findings support the idea that mice are useful models for human brain research.

"Our findings indicate that the molecular mechanism of ultrafast endocytosis is conserved between mice and human brain tissues," says cell biologist Shigeki Watanabe, from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

The 'zap-and-freeze' method is just one of several techniques neuroscientists have been developing recently to capture snapshots of active synapses in near-living tissues.

When it comes to Parkinson's disease, knowing more precisely how these synapses and vesicles work together should help to shed some light on what might be going wrong in Parkinson's brains – and potentially, how to repair it.

That's still a long way off, but we know that neurons in the brain die as Parkinson's progresses, with cell death thought to be related to some extent to faulty synapses. Parkinson's is a complex disease, though, and untangling the consequences of the condition from the driving forces isn't straightforward.

Next, the researchers hope to obtain tissue samples, with permission, from Parkinson's patients already undergoing invasive brain procedures. Those samples could show how vesicle activity differs in brains affected by the disease.

With Parkinson's already affecting millions worldwide, and expected to become even more prevalent in the coming years, techniques such as 'zap-and-freeze' could be crucial in mapping brain activity on the smallest scales and shortest timeframes.

"We hope this new technique of visualizing synaptic membrane dynamics in live brain tissue samples can help us understand similarities and differences in nonheritable and heritable forms of the condition," says Watanabe.

The research has been published in Neuron.