We know mosquitoes are a serious threat to our health as human beings– in fact, they're the world's deadliest animal, with mosquito-borne diseases responsible for more than a million deaths a year.

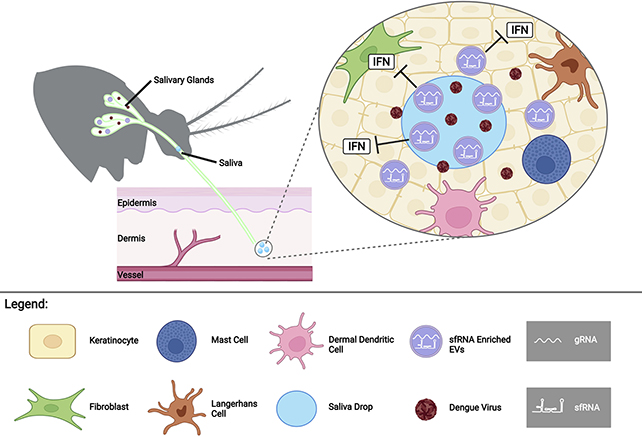

And it's not just their bites that we need to worry about. New research shows how the saliva of a mosquito carrying the dengue virus is loaded with a substance that may suppress our immune system response and increase the risk of infection.

Through three separate analysis methods, scientists identified a specific type of viral RNA, or chemical messenger, called sfRNA in the infected mosquito saliva. It essentially blocks the defense mechanisms the human body puts up against infection.

"It's incredible that the virus can hijack these molecules so that their co-delivery at the mosquito bite site gives it an advantage in establishing an infection," says biochemist Tania Strilets from the University of Virginia.

"These findings provide new perspectives on how we can counteract dengue virus infections from the very first bite of the mosquito."

The sfRNA is loaded in membrane compartments called extracellular vesicles, ready for delivery. The dengue virus appears to "subvert mosquito biology", in the words of the researchers, to give it a better chance of spreading.

In tests on immortalized cell lines, the team confirmed that this sfRNA payload did indeed increase virus infection levels – laying the groundwork so that the human body isn't quite so well prepared for attack.

These sfRNAs have been spotted before in insect-borne viruses, including Zika and yellow fever. Their role, more generally, seems to be to get in the way of the chemical signaling used by the body as the virus replicates.

"We propose that by introducing this RNA at the biting site dengue infected saliva prepares the terrain for an efficient infection and gives the virus an advantage in the first battle between it and our immune defenses," write the researchers in their published paper.

Dengue is a serious issue, with around 400 million people infected every year – and reinfection is possible. Symptoms include fever, nausea, and a skin rash; in a small number of cases, it can lead to internal bleeding or even death.

Right now, there's no way of treating the virus, only methods for managing the symptoms. While we're still some way from a drug to treat dengue, understanding more about it and how it spreads is essential in fighting it.

The team is hopeful that its discovery can lead to better preventive measures against the dengue virus right from the moment of infection, but the best way of keeping yourself safe remains the same as before: avoid getting bitten.

"There is no doubt in my mind that better understanding of the fundamental biology of transmission will eventually lead to effective transmission-blocking measures." says virologist Mariano Garcia-Blanco, from the University of Virginia.

"Our findings are almost certainly going to be applicable to infections with other flaviviruses. The specific molecules here are unlikely to apply to malaria, but the concept is generalizable to viral infections."

The research has been published in PLOS Pathogens.