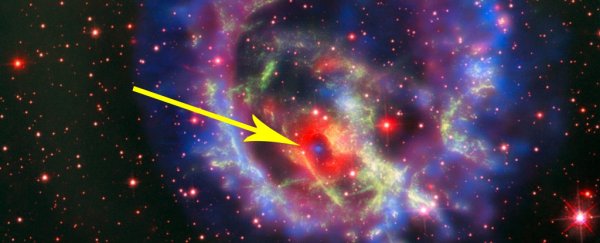

For the first time, astronomers have found something we have never seen outside the Milky Way - a low magnetic field neutron star without a binary pair. And it's surrounded by a truly unusual ring of cool gas.

The supernova remnant SNR 1E 0102.2–7219 (or E0102 for short) is about 2,000 years old, located in our galactic neighbour, satellite dwarf galaxy the Small Magellanic Cloud.

It looks a bit like a bubble - but inside is a tangled web of filaments as the dust and gas from the stellar explosion continue to move outward into the cosmos.

Thanks to images taken with Hubble, Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Very Large Telescope's MUSE instrument, an international team of researchers managed to find the supernova's source hidden among these fast-moving filaments.

The puzzle started when MUSE data revealed something odd.

"The team identified a torus [doughnut shape] of relatively cold - approximately room temperature - slowly expanding gas, consisting predominantly of oxygen and neon," said lead researcher Frédéric Vogt, an astronomer and astrophysicist at the European Southern Observatory.

Inside this doughnut was an X-ray source that had been noted down years before, and named p1. But what p1 was - and where it was - remained a mystery. And the "where" was key.

Was it inside the supernova, or somewhere far behind it?

(ESO/NASA, ESA and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)/F. Vogt et al.)

(ESO/NASA, ESA and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)/F. Vogt et al.)

The MUSE data showed that the ring perfectly circled the X-ray source. Wonderfully coincidental cosmic alignments do occur, but this was a little too coincidental - the X-ray source had to be inside the ring.

Once the location was pinned down, previously collected Chandra data revealed that the source was an isolated neutron star with a low magnetic field.

These are very small neutron stars, which constitute one of the possible end stages of the life cycle of a high-mass star.

Once a star has gone supernova, exploding most of its material out into the surrounding space, its core collapses into either a neutron star or a black hole, depending on mass. If the core is smaller than about three times the mass of the Sun, it turns into a neutron star.

Generally, they're around 20 kilometres (12 miles) across, but isolated low magnetic field neutron stars are around half that size. They're also harder to spot than binary neutron stars because they typically don't emit as much X-ray radiation - and they don't emit any visible light at all.

The object - the neutron star and the ring - is a peculiar one. It's the first time a cool ring-shaped structure consisting primarily of oxygen and neon has been identified in the vicinity of an isolated neutron star.

"Though it surrounds the cooling neutron star, we have not yet conclusively found an explanation for the origin of the torus," said researcher Ivo Rolf Seitenzahl, an astrophysicist with the University of New South Wales in Australia.

"We're quite sure that it is almost certainly related to the supernova explosion and the formation of the neutron star, however, we are still unclear about when, how, and why the torus was formed."

One possible explanation is that the neutron star did once form part of a binary system, cannibalising its companion star and stripping it of material until nothing was left.

E0102 isn't just a cosmic curiosity; there's a lot we don't know about supernovae. The fact that the neutron star was found in a nebula - literally the corpse of the star it once was - allows researchers to study the before and after.

"This study provides a direct link between the detected remnant - a neutron star - and its predecessor, the progenitor star," said researcher Ashley Ruiter, also an astrophysicist at the University of New South Wales.

"Making such links helps us better understand the explosion mechanisms of supernovae."

The team's research has been published in the journal Nature.