Based on marks on an ancient bone, it seems someone got hungry enough to chow down on some hominin leg, some 1.45 million years ago.

It's not an unknown behavior, over the years. But the tibia, marked with cuts, and belonging to a mystery human relative who used to live in what is now Kenya, may represent the oldest example we've seen yet of hominin-on-hominin butchery.

A team led by paleoanthropologist Briana Pobiner of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History has performed a detailed, 3D analysis of the cuts, and performed experiments on bone to see what made them.

Their findings show that the marks were made by stone tools, in the manner of stripping the flesh in preparation for eating.

"The information we have tells us that hominins were likely eating other hominins at least 1.45 million years ago," Pobiner says.

"There are numerous other examples of species from the human evolutionary tree consuming each other for nutrition, but this fossil suggests that our species' relatives were eating each other to survive further into the past than we recognized."

Although a study published last year found that humans and our relatives and ancestors occupied a pretty primo position on the food chain over the last couple million years, hominins do, occasionally, end up as brunch for something with pointier teeth.

Not as often as you might suppose, though, so Pobiner undertook a study of ancient fossilized hominin bones looking for signs of carnivory.

On one bone, though, from the archaeological sites in Koobi Fora, Kenya, and dated to 1.45 million years ago in the Early Pleistocene epoch, she found something unexpected.

Rather than the tooth marks of something lionesque, she found what looked remarkably like deliberate cuts.

This is actually more common than you might think throughout hominin history.

Often, such cut marks are ritual in nature, part of the process of interring the dead. It was also way more common than you might think that humans carved the bones of other humans into decorative objects, such as combs, pendants, and other jewelry.

Occasionally, however, it's evidence of something else: anthropophagy, the eating of human flesh by other humans – although not necessarily the same species of human, which would mean it's not, strictly speaking, cannibalism.

Ancient anthropophagy is difficult to prove. The purpose for which the bone was processed could be misinterpreted, in the absence of other evidence. Even so, there are some Pleistocene bones for which the interpretation of cannibalism or anthropophagy is uncontested.

To determine what the scars on the bone were, Pobiner created a mold of the bone using dental molding material, and sent it to paleoanthropologist Michael Pante of Colorado State University to see what he might make of the marks.

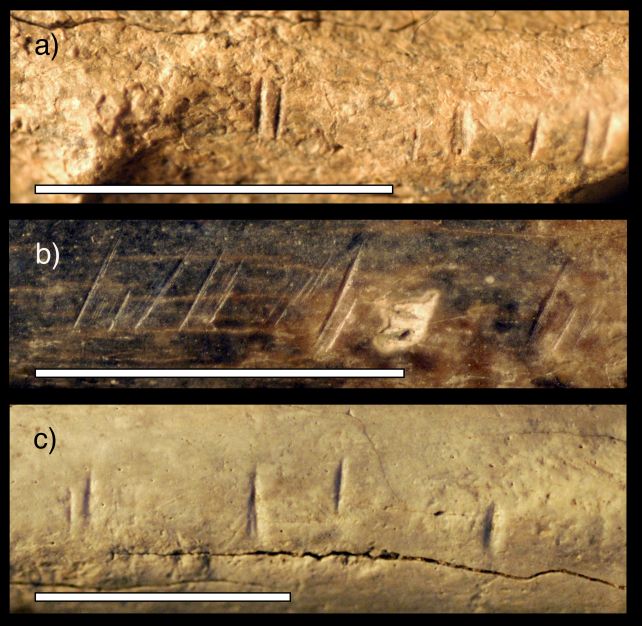

He scanned the mold, and compared it to a database of 898 tooth, trample, and cut marks that have, over time, been carefully created during controlled experiments, and put together into a resource for just this purpose.

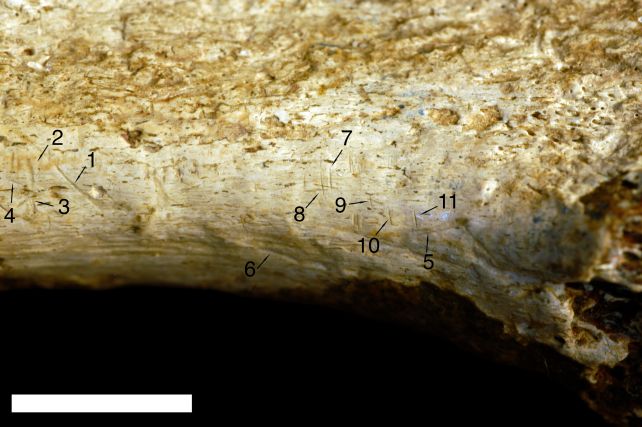

The results of this were pretty clear. Nine of the 11 marks on the bone, Pante found, were unequivocally cut marks, consistent with the sort of damage made by stone tools.

The other two were tooth marks, similar to those made by a lion.

It's unclear which came first, the cutting or the lion, but the cut marks, Pobiner says, are consistent with those made by removing flesh from a bone – for example, in preparation for eating.

They are all angled and oriented the same way, as though the person making them was chopping, without changing their grip on the stone tool, or moving. And they're all located where the calf muscle would have been attached to the bone. That's the perfect spot to chop if your goal is deboning a hunk of meat.

"These cut marks look very similar to what I've seen on animal fossils that were being processed for consumption," Pobiner says.

"It seems most likely that the meat from this leg was eaten and that it was eaten for nutrition as opposed to for a ritual."

We don't know who was doing the eating, or even who was eaten, in terms of species.

When the leg bone was scientifically described in the early 1970s following its discovery, its owner was identified as Australopithecus boisei. It was reidentified in the 1990s as Homo erectus.

However, archaeologists and anthropologists have since determined that we just don't have enough data to make a species identification.

And we certainly don't know what species of hungry hominin made the cut marks.

It could have been any number of contemporaneous hominins. So while we can't rule out cannibalism, nor can we make an absolute declaration in that direction.

The closest we can come is anthropophagy.

The other question that remains unanswered is whether or not it really is the oldest known evidence of anthropophagy.

There's a skull, between 1.5 million and 2.6 million years old, which has marks interpreted as made by a stone tool. That finding has been disputed; perhaps it's time we revisited that bone.

And there might be other such fossils, lurking in museums, waiting for people to come along and read the marks thereon in the language of history.

"You can make some pretty amazing discoveries by going back into museum collections and taking a second look at fossils," Pobiner says.

"Not everyone sees everything the first time around. It takes a community of scientists coming in with different questions and techniques to keep expanding our knowledge of the world."

The findings have been published in Scientific Reports.